Creating Wonder: A Discussion with Kristi McMillan, Assistant Curator of Education for Visitor Engagement at the Birmingham Museum of Art

This interview focused on technology in educational programming at museums and was conducted via email between Amy Williamson and Kristi McMillan, Assistant Curator of Education for Visitor Engagement at the Birmingham Museum of Art (BMA) in Birmingham, Alabama. In summer and fall of 2014, Williamson served as an intern at the BMA.

Q: Talk about the BMA’s avenues for visitor engagement.

We engage visitors with artworks through facilitated and self-guided interpretation. Facilitated interpretation can include tours, workshops, lectures, performances, and outreach; self-guided interpretation is defined more broadly, from exhibition design and signage to interactive spaces, technology, and printed material. Education, curatorial, communications, and new media staff work together on these efforts. We’re successful if we can build a bridge between a visitor and an object; provide understanding or create wonder about human creativity; or best of all, help a visitor associate an object – perhaps made in another part of the world at a different time by people living lives wholly unlike theirs – with their own experience. This definition of success may seem lofty and hard to measure, but we see sparks of connection happen every day.

Q: The Mystery Object kiosk and “Who Done It?” stations are no-tech but exceptionally popular. Why is there such high participation?

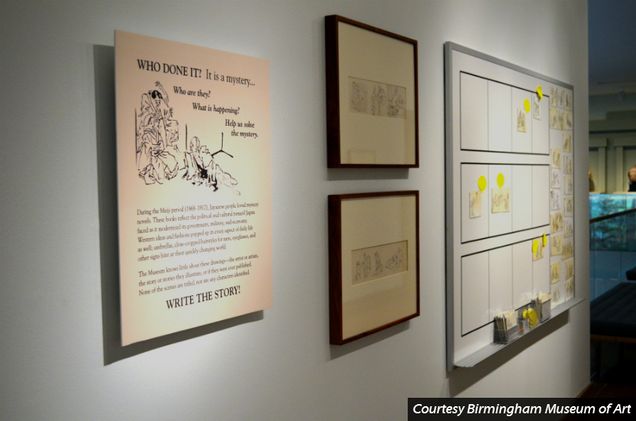

In 2011, our eighteenth-century English gallery was completely reinstalled, allowing curatorial and education staff to reconsider interpretation. Some decorative arts objects may look strange to twenty-first-century eyes because we no longer use them. At the Mystery Object kiosk, we feature such objects and ask visitors to respond to one of three questions: What do you want to know about this object?, What are the first three words that come to mind when you look at this object?, How would you use an object like this in your life? Visitors display their responses and visit our website to learn more. While we receive some unengaged responses – think “John was here” – about 95 percent engage directly with the prompts. We even regularly see responses where visitors write on earlier ones – answering questions, providing information, or “seconding” what someone else wrote. The “Who Done It?” station related to a collection of nineteenth-century Japanese drawings. We acknowledged that we knew little about them and invited visitors to provide captions and/or put together reproductions to tell a story, on a board adjacent to the installation. Visitors’ mini-dramas, comedies, and tragedies covered the board for months. Both projects are no-tech with simple materials. They encourage visitors to think creatively, rather than the expository thinking privileged by school and work. They allow personalities to come through; responses are often humorous or insightful. People like to share their opinions and become agents in their own learning process.

Q: How does participation in no-tech interactives compare to experiences built around digital technology? Is technology important for visitor engagement in the twenty-first century?

In the past few years, the BMA has experimented with a range of low- and high-tech interpretation. Our visitors tend to use low- (e.g. cell-phone tours) and high-tech (e.g. mobile applications) tools more when they’re linked to specific exhibitions (40 to 50%) rather than the collection (about 10%). Even at 10 percent, though, usage of our app to access collection material is considered “fairly exceptional” by colleagues in the field. When planning interpretation, it’s important to consider what role an interpretive tool plays in the presentation of an object. Rather than using technology for technology’s sake, we think about what it can uniquely add that a no-tech method cannot. And, we shouldn’t forget that many people visit museums to “turn off” – to escape from the constant accountability that personal devices demand. Museums can be that place of repose and rejuvenation, and too much technology can run counter to a desire to just be. Now, I am a tech-lover, excited about the possibilities that technology has for connecting visitors with art; but visitors’ embrace of technology can be slow. In a free-choice learning environment, we layer a range of interpretive tools to meet visitors where they are, to respond to different motivations for visiting and learning needs – so that visitors can tailor their experience. When visitors feel comfortable, they may come more frequently.

Q: Where do you see visitor engagement going in the next five to ten years? What role will technology play?

Our staff talks to visitors about their experiences. We think about why people come, what they need, and how we can provide it; [we reflect on] our successes, challenges, [and] insights. We consider how a visit to the BMA is a unique part of the Birmingham experience. In response, we are continually tailoring the BMA to be a more welcoming place. There are myriad options competing for people’s leisure time, and we can no longer assume that museums are a “given.” In the past twenty years, museums have made a remarkable shift to be more visitor-centric. In the next five to ten years, we’ll continue in this direction: investing time, energy, and resources to build meaningful and transformative connections with visitors and between visitors and artworks, and finding compelling ways to make technology work in the service of bridge-building, to unlock the secret lives of objects and to unmask the work of museums.