Outside the Gate: The Seduction of Belonging in the Charleston works of Elizabeth O’Neill Verner

“To the artist the spirit rather than the letter is the important thing.” [1]

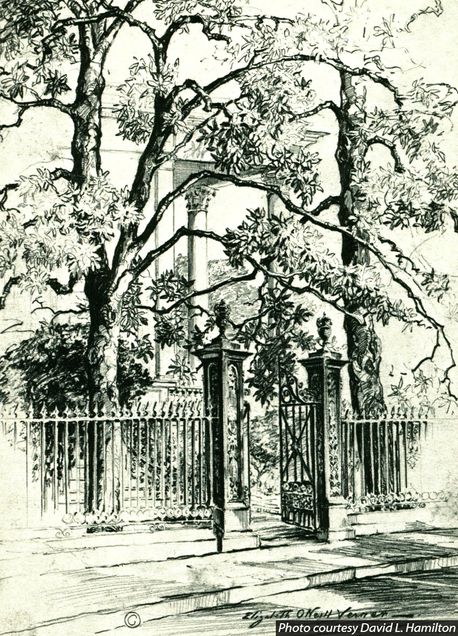

Thus wrote Elizabeth O’Neill Verner (1883-1979), a sketcher and printmaker focused on depicting the stark contrasts between light and dark in her hometown of Charleston, South Carolina. Light and dark is meant both literally and figuratively here, as Verner did much of her drawing out of doors on the streets under the brilliant South Carolina sunlight. She focused her gaze on the obscured edges of a shady garden or on a tree-shrouded aristocratic home peeking from behind a wrought iron fence. Her most enchanting images are ones in which she let the play of light and shadow dapple across surface creating a sense of calm and nostalgia, as seen in Gates of the Mikell Jenkins House. (Fig. 1) Of Verner’s numerous sketches and etchings of Charleston, some were compiled into book format and published, accompanied by lyric essays by Verner herself on the history and culture of the city. The images in this article, which are representative of her graphic work from the 1920’s and 30’s, were taken from two of Verner’s publications, Mellowed by Time (1941) and Prints and Impressions of Charleston (1945). While her depictions of Charleston are sentimental, Verner never pictures a Southern belle to complete the air of ante-bellum prosperity. She relied instead on a completely different cast of characters.

In spirit Verner was a true Charlestonian, but in letter she did not move within the same social sphere as elite Charlestonians. The O’Neill family was Irish Catholic and they were never plantation owners, although she would later join a Presbyterian congregation and forge professional relationships with her social betters. In this way, Verner was a social outsider trying to gain acceptance into the upper echelons of Charleston society. She was also a committed professional artist who trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and, as a founding member of many cultural groups including the Charleston Etchers’ Club and the Southern States Art League, became an important figure in the Charleston Renaissance of the 1920’s and 30’s. [2] However unlike other female members of the Charleston art scene who hailed from “old Charleston” families, such as Alice Smith, Verner gained respect not by birthright but through hard work. [3] Following the death of her first husband in 1925, she began drawing and etching twelve to fourteen hours a day to support her household. [4] Verner’s images indicate that her relationship to Charleston’s high society remained a working one, while her liminal social position was reflected in her artistic practice. Rather than sketch the interiors of the homes and gardens she so admired, Verner stayed on the pavement outside, drawing endless views of gardens as seen through the main gate.

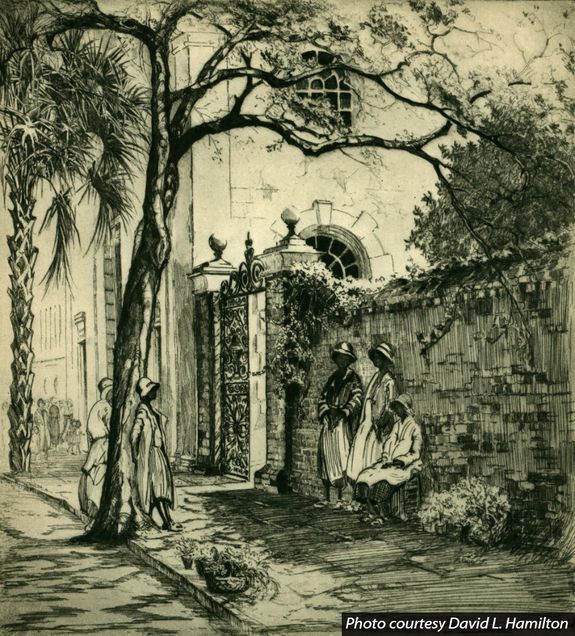

This is not to say that Verner’s views of Charleston are unpopulated images of homes and gardens. Often people are scattered around the gates, walking, sitting, working, or conversing, as in Springtime in Charleston. (Fig. 2) These individuals are almost all African American, members of the Gullah people of the coastal South. They shaped the character of Verner’s streets as much as the vestiges of old plantation aristocracy formed her images’ backdrops. Significantly, Verner’s writings about the Gullah and their traditions are sentimental and, at times, so willfully cloying and condescending that it can be difficult for today’s reader to stomach her narratives. She described the Gullah people, especially those living in the surrounding Low Country, as primitive or child-like and placed herself in an obvious position of superiority over them. For example, when trying to explain why the Gullah might not want their pictures taken by tourists, Verner concludes: “They cannot explain why they act thus, but any anthropologist could tell you of a universally primitive aversion to having the soul captured on canvas or paper.” [5] Seen in this light, one might wonder at the widespread presence of Charleston’s black population in her etchings, and to what extent the Gullah approved of her portrayals of them. Indeed, an analysis of Verner’s images alongside these writings exposes her complex relationship with Charleston and all its inhabitants. Oscillating between the sentimental and the observational, the hidden and the displayed, her artworks reveal that her own position as artist was a negotiated one, wherein she navigated between local superstition and high-society life.

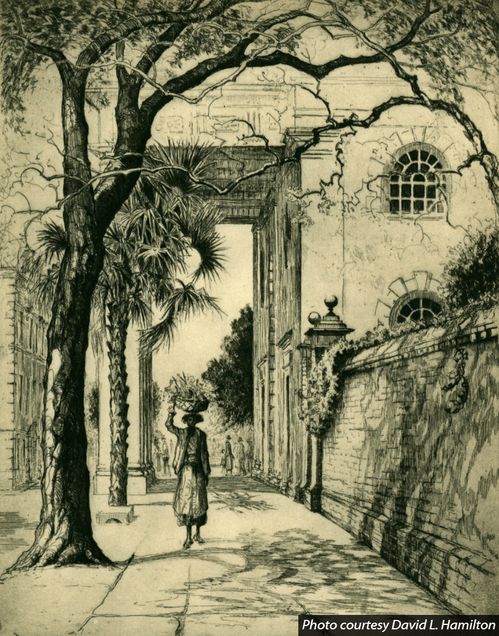

Verner’s attempts to preserve the unique character of Charleston’s streets and sidewalks on paper were not conducted in a vacuum. In her art, her viewpoint towards the homes and gardens of elite Charlestonians was a shared one. Both she and Charleston’s black population stood outside the gate. Perhaps Verner recognized the links between her own position wandering the streets of Charleston at work with pencil and paper and that of the black flower women she used as frequent models, who also plied their trade on the sidewalk. Indeed, when the city threatened to banish the flower women from its streets, Verner spearheaded a campaign to protect their trade. [6] This might also explain why these supposedly camera-shy women allowed Verner to drawn them. The very direct, proud stance of the flower woman walking towards the artist in Under the Shadow of St. Michael’s seems to gesture towards this camaraderie between female professionals, both upholding Charlestonian traditions through their labor. (Fig. 3)

In contrast to her depictions of Charleston’s center, her prints of the surrounding Low Country reveal Verner at a disadvantage, for, while there were no tall garden walls to keep her out, the unease of rural residents at having their homes sketched still kept her at the edge of the yard. In some cases, she was forced to meet residents’ demands, as with Manda’s Cabin, (Fig. 4) which was drawn on the condition that Verner correct the sagging roofline. [7] In her writings on the subject, however, Verner refrained from calling herself an outsider in these settings. She falls back on an anthropological attitude, explaining the reluctance of Low Country occupants at having their homes sketched in terms of superstition and a local fear of the amorphous “plat eye.” [8]

Thus, no matter whether she set out to sketch the Mikell Jenkins House in downtown Charleston or Manda’s cabin in the Low Country, Verner’s viewpoint was often from a marginal position outside a gate or at the edge of the yard. The viewer of these images retains the odd impression of an artist deeply in love with a place that is both hers and not. Undeniably, there are two impulses at work in these images. The first was Verner’s repeated desire to document Charleston as she saw it before it slipped away into the past. The second was to convey an authentic character of the city, which Verner maintained could provoke mixed emotions in viewers, and which was carefully guarded by many inhabitants.

Verner herself acknowledged the difficulty of negotiating and expressing her own identity as related to place when she wrote: “It is so difficult for a Charlestonian to write about Charleston without becoming either sentimental or austere.” [9] One wonders: would revealing all of the darkness and light of Charleston take away from the veneer of serene dignity and quaint superstition that she tried to project? Art and literature critic Louis D. Rubin, Jr. wrote: “Miss Beth’s gates do not say, keep out! They say, Won’t you look within at the garden?” [10] Indeed, the gates are seductive, but Verner said it better herself when she wrote: “the best of Charleston is enclosed.” [11] In Verner’s images of Charleston, the gates shut in an entire world of verdant white privilege. The forms of palmetto fronds and the veranda corner peeking above the iron scrollwork of the gate can be seen, while the interiors of these homes remain private. Similarly, the straightened roof of Manda’s dilapidated cabin and the pride and pretty dresses of the flower women speak to an anxiety about curating a self-image for the city’s African American residents. Indeed, in Verner’s images there is much that is left untold, hidden both from the artist and from the viewer.

Olivia J. Kiers

____________________

Endnotes:

[1] Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, Mellowed by Time: A Charleston Notebook, 3rd ed. (Charleston, SC: Tradd Street Press, 1978), 1.

[2] See Stephanie E. Yuhl, A Golden Haze of Memory: the Making of Historic Charleston (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 74-76.

[3] See Yuhl, A Golden Haze of Memory, 74-76.

[4] Boyd Saunders, “Alfred Hutty and the Charleston Renaissance,” in Graphic Arts and the South: proceedings of the 1990 North American Print Conference, ed. Judy L. Larson (Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1993), 235.

[5] Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, Prints and Impressions of Charleston, (Columbia SC: Bostick and Thornley, 1945), section XI (unpaginated).

[6] Yuhl, A Golden Haze of Memory, 85-86.

[7] Verner, Prints and Impressions of Charleston, section X.

[8] Verner, Prints and Impressions of Charleston, section XI.

[9] Verner, Prints and Impressions of Charleston, section I.

[10] Rubin, Louis D, Jr., foreword to Mellowed by Time: A Charleston Notebook, by Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, 3rd ed. (Charleston SC: Tradd Street Press, 1978), x.

[11] Verner, Prints and Impressions of Charleston, section IX.

For further reading

Pollack, Deborah C. Visual Art and the Urban Evolution of the New South. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2015.

Saunders, Boyd. “Alfred Hutty and the Charleston Renaissance.” In Graphic Arts and the South: Proceedings of the 1990 North American Print Conference. Edited by Judy L. Larson. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Verner, Elizabeth O’Neill. Prints and Impressions of Charleston. Columbia, SC: Bostick and Thornley, 1945.

Verner, Elizabeth O’Neill. Mellowed by Time: A Charleston Notebook. 3rd ed. Charleston, SC: Tradd Street Press, 1978.

Yuhl, Stephanie E. A Golden Haze of Memory: The Making of Historic Charleston. Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.