HBR: Are You Missing Growth Opportunities for Your Platform?

May 2, 2025

Four ways to scale.

by David J. Bryce, Jeff Dyer and Marshall W. Van Alstyne

Seven of the world’s 10 most valuable companies have launched platform businesses, as have over 60% of unicorn startups. Many companies that didn’t start out as platform businesses—from retailers Walmart and Amazon to software providers Salesforce and ServiceNow—have also successfully accelerated their growth through platform strategies. But numerous companies have missed out on growth opportunities. Why does one platform company succeed at growth while another does not? The authors’ research points to four main reasons: Unsuccessful firms don’t systematically consider all growth options; they mistakenly believe they must own the various kinds of interactions that occur on the platform, not realizing that huge growth often lies in not owning them; they overlook options to engage companies that can add value or even disrupt their businesses; and they don’t identify a compelling theme that broadens their scope. This article offers guidance for overcoming those impediments to growth.

Digital platforms have been remarkably successful businesses for both native platform firms and traditional corporations. Seven of the world’s 10 most valuable companies have launched platform businesses, as have over 60% of unicorn startups. Many companies that didn’t start out as platform businesses—from retailers Walmart and Amazon to software providers Salesforce and ServiceNow—have also successfully accelerated their growth through platform strategies.

But numerous companies have missed out on growth opportunities. Consider the race between Uber and Lyft in the ride-hailing market. Uber launched a host of complementary services on its platform, adding icons in its app for “Eats” (food delivery), “Package” (same-day delivery), “2-Wheels” (rentals of bikes and scooters), and “Rent” (rental cars). That move required Uber to recruit new service providers—restaurants and rental car companies, for example—to the platform. In contrast, Lyft remained focused primarily on ride hailing. Not surprisingly, Lyft’s revenues have grown relatively modestly, from $3.6 billion to $4.4 billion over the past five years, while Uber’s have climbed from $13 billion to $37 billion. Other examples of firms that have failed to pursue platform growth opportunities include Craigslist, which has not added a payment system, and Disney, which lacks a marketplace for licensed third-party sellers.

Why does one platform company succeed at growth while another does not? Our research on the paths of more than 50 platform companies, including several that have become platform giants, points to four main reasons: Unsuccessful firms don’t systematically consider all growth options; they mistakenly believe they must own the various kinds of interactions that occur on the platform, not realizing that huge growth often lies in not owning them; they overlook options to engage companies that can add value or even disrupt their businesses; and they don’t identify a compelling theme that broadens their scope.

In this article, we offer guidance for overcoming those impediments to growth.

The Four Growth Opportunities

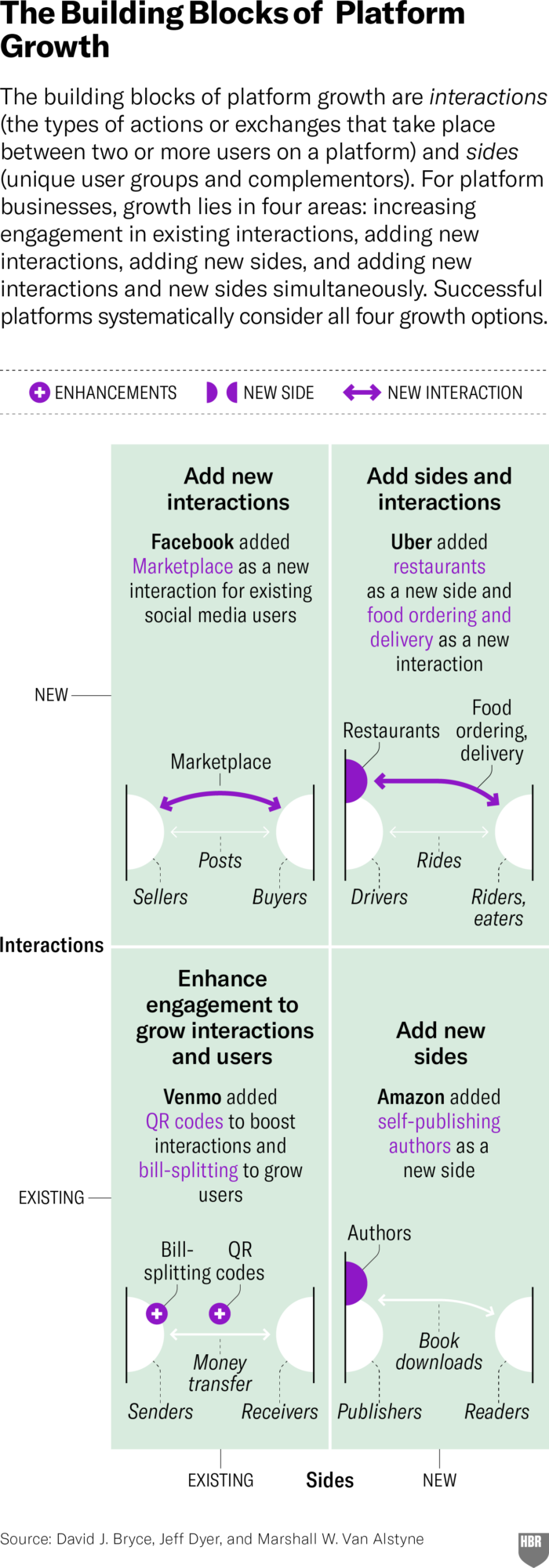

The building blocks of platform growth are interactions (the types of actions or exchanges that take place between two or more users on a platform) and sides (unique user groups and complementors). For example, Uber’s interactions include ride hailing, food delivery, and so on; the sides consist of all the complementary companies that offer services on the site and all the users that consume those services.

For platform businesses, growth lies in four key areas: increasing engagement in existing interactions, adding new interactions, adding new sides, and adding new interactions and new sides simultaneously. Platform owners use the tools of architecture (the interfaces and technical design of the platform) and governance (the rules and incentives for participation) as levers to add and grow sides and interactions. (See the exhibit “The Building Blocks of Platform Growth.”)

Increase engagement.

This opportunity involves growing the number of users on the platform and boosting the number of interactions per user. That may seem basic, yet some managers fail to relentlessly incentivize participation and improve the interaction experience. Venmo, the peer-to-peer money transfer platform, initially offered cash incentives—for example, direct payments to users who refer a friend—and the ability to request payments as it grew its user base. But it took nearly eight years before the company added additional engagement features such as instant transfer, where a recipient could get access to transferred funds instantly, and a QR code scan feature for making payments to individuals and businesses. That delay allowed Cash App, a similar peer-to-peer digital wallet launched four years after Venmo, to capture 45% of the market. Cash App introduced several engagement features, such as instant deposit, well before Venmo made similar moves.

The lesson? Platform companies should introduce features that build engagement even while they’re growing the user base in order to expand network effects and lower the likelihood that users will switch to competitors. Venmo’s recent actions have helped the company grow its user base from 40 million to 95 million in the past five years, while also increasing the number of transactions per user.

Add new interactions.

Companies may choose to add complementary interactions or substitute interactions to enhance growth. A complementary interaction is one that adds value to an existing side because it enhances the value or utility of other interactions. For example, Facebook (now Meta) launched Facebook Marketplace in 2016 after discovering that many users were posting items for sale in Facebook groups. To make the buying and selling of goods easier for users, it added the marketplace, which not only increased engagement among existing users but also pulled in new users. Facebook then used governance levers to establish rules for quality, such as excluding nonproduct postings and providing promotional incentives and shipping discounts for buyers. Those improvements propelled Facebook Marketplace ahead of Craigslist.

A substitute interaction provides a way for a user to get a job done on the platform instead of using a different platform or service. An example is Facebook Dating, which launched in 2019. It allows users to engage in social interactions on the site, eliminating the need to leave the platform to interact on dating apps.

Adding substitute or complementary interactions allows platforms to generate new network effects by increasing the frequency with which existing users exchange value on the platform and attracting new users.

Add new sides.

Companies can increase the volume of interactions by adding new sides that share interests with existing sides or that can be served with existing platform resources. An example of the former comes from Amazon, which allowed authors (a new side) to self-publish alongside publishers (an existing side) and sell directly to book buyers. By adding this new side, Amazon significantly increased the number of books offered on its platform. An example of the latter is Walmart, which let suppliers list products for sale directly on Walmart.com, leveraging the retailer’s ordering and checkout process. The new sides increased the value of the platform for all participants and boosted user engagement by adding variety. The launch of Walmart Marketplace eventually increased the number of products available to consumers more than 10-fold, yielding annual marketplace revenues of $82 billion.

Add new sides and new interactions simultaneously.

When new sides and new interactions are added as a bundle, the platform’s total volume of interactions can grow rapidly. Uber used this strategy when it simultaneously added food order interactions and restaurant sides to its ride-hailing platform, creating Uber Eats. Another way companies can add new sides and interactions simultaneously is to add other established platforms—along with their unique user groups and interactions—to their own, as Uber did when it added the e-bike and scooter platform Lime.

It’s important to note that platform managers should build the critical mass necessary for self-sustaining growth in existing interactions—where the network-effect flywheel kicks in—before diverting resources to new sides or new interactions. Moving too fast can spell disaster. Rdio, a music-streaming service launched by the founders of Skype, started with social features in music streaming. The company added video streaming before the core music service had sufficiently taken hold, and the overextension ultimately led to Rdio’s bankruptcy filing just five years after launch. Too much breadth and too much complexity too fast can be deadly.

Share the Growth Opportunity

Managers often believe they must own—buy or build—the interactions available on their platform, yet huge growth lies in not owning them all. Acquisitions are costly because successful platform firms command high premiums, and internal expansion is typically slow and limited to the company’s own ideas and resources. A more effective approach is to partner with complementary platforms or apps that are gaining traction and whose offerings align with the needs of existing users. Companies can identify those needs by asking users what’s missing, deploying data analytics to profile users and understand their activity, and tracking traffic on and off the platform to see where users are going and where they’re coming from. By forming partnerships, platform firms consolidate services into a single access point and generate network effects through shared users, data, and costs, thereby benefiting all parties. Partnerships can deliver new value to users quickly and cost-effectively while avoiding the challenges of acquisition.

A case in point is Tencent. It partnered with more than two dozen companies on its WeChat platform—including JD.com (e-commerce), Pinduoduo (e-commerce), DiDi (ride hailing), and Meituan (food delivery)—and grew its number of users to one billion. Let’s look in more detail at JD.com. In 2014 Tencent acquired a 15% stake in the platform. As part of the deal, JD.com got immediate access to Tencent’s large user base. At the time of the deal, JD.com’s market value was $22 billion. By integrating JD.com into its platform and promoting it to users, Tencent helped JD.com grow by 431 million users over seven years, boosting its market value to $88 billion. Meanwhile, Tencent’s stake grew to over $13 billion in value.

In contrast, U.S. companies often pursue a build-or-buy approach. Google built several platforms internally, such as Google+ (social media), Google Buzz (a Twitter knockoff), Google Offers (a Groupon clone), and Google Video (for content streaming). But Google might have had more success if instead of challenging established platforms with their existing network effects, it had partnered with them. Google has since shut down all those platforms and in some cases has turned to acquisition to enter a space—as it did with its purchase of YouTube.

When Alibaba launched its B2B platform, it initially failed to gain traction. The situation changed significantly after the company pivoted to engage strategic partners. Ming Zeng, the former chief strategy officer at Alibaba, pointed out that while building with partners requires giving up some control, benefits abound, including attracting partner investments, lowering risk, and avoiding costs if partner offerings fail.

Platform companies should build engagement features even while they’re growing the user base to expand network effects and lower the likelihood that users will switch to competitors.

To be successful, platform partnerships should create interdependencies among interactions by sharing data, maintaining compatible platform architecture, integrating payment systems, and more. This aligns incentives so that each partner benefits from the other’s success. Our research shows that minority equity investments are an effective way to achieve alignment, although a carefully written contract or customized technology integration could achieve similar goals. With equity investments, the larger partner typically holds a minority stake in the smaller one. For example, Tencent’s average initial stake in 17 of its partners was 18%, while Alibaba owned an average initial stake of 20% in 15 of its partners. Equity aligns partner interests more effectively than contracts because it provides a direct financial incentive to maximize value, which motivates partners to commit more knowledge and resources to the collaboration. Over time, an initial equity stake can serve as a stepping stone to an acquisition. For instance, Tencent acquired a minority stake in KuGou, a music platform, before purchasing it outright. Baidu did the same with Nuomi, a Yelp-like review platform.

Partnering with a business that acts as a substitute for a platform’s own offering might seem counterintuitive, as it could reduce the value of its offerings. However, there are scenarios where such partnerships make sense, such as when they deter competitors from developing alternative platforms. Kloeckner Metals took this approach when launching its metals marketplace to achieve critical mass and deter others from entering the space. In cases where a substitute poses a significant threat, acquiring it might be the best strategy, as was the case when Facebook acquired Instagram, a direct competitor.

Open the Platform to Affiliates

Managers can become so focused on growing users of their own platforms that they overlook the many innovations launched by rival platform companies. Myspace missed Facebook’s social gaming; Foursquare missed Yelp’s customer reviews of locations; Snapchat missed Instagram’s photo posting and monetization tools for content creators. Some managers ignore such innovations; others actively block them. When Intuit first attempted to convert QuickBooks, its desktop accounting software, to a platform, the company refused to give outside developers access to the best tools and APIs, fearing that companies like PayPal or Square (now Block) would tap those developers to create something even more useful and become competitors. The result? Innovation was stifled, and PayPal and Square did not develop useful apps—and neither did anyone else. Then-CEO Brad Smith ultimately decided that the company should open the platform to everyone, and Intuit now boasts a valuable platform ecosystem.

While partnering requires giving up some control, benefits abound, including lowering risk and avoiding costs if offerings fail.

To profit from the innovations of numerous other players in an ecosystem, a platform doesn’t need to acquire or partner with them. Instead, managers can open the platform to arm’s-length affiliates that meet certain criteria and adhere to rules of governance. In this way platform managers can capture new ideas from people they don’t even know, lowering the risk of their own irrelevance. The strategy is especially useful when the variety and scale of use cases exceed what one company can build or even understand. Multiple businesses have launched on Tencent’s WeChat platform without its direct involvement. Their offerings include financial services (China Asset Management and GF Fund), travel services (Ctrip), lifestyle and e-commerce (Xiaohongshu), and cooking and recipe sharing (Xiachufang). Similarly, Salesforce allows developers to sell a wide range of sales tools on its AppExchange, catering to customer needs not covered by its software.

At launch, platforms should affiliate only with firms that create complementary network effects; they should avoid inexperienced entities that might damage their reputation. When its interactions are stable and its reputation and network effects are established, a platform can afford to be more welcoming, but managers should continue to monitor the platform and remove affiliates that violate policies or otherwise negatively impact the ecosystem. And of course, managers should ensure broad strategic alignment with all affiliates and watch for competitive cannibalization.

Platform owners can permit affiliates to try their ideas with little management involvement by architecting the platform with structured interfaces and governing with default contracts, such as those detailing rules for royalties, user access, and data sharing. Owners can analyze user metrics and feedback to identify promising interactions and promote the best ones through personalized recommendations, featured placements, and targeted notifications. In doing so, platform owners maximize affiliate visibility and user satisfaction.

A key decision for platform businesses is what type of relationship to have with the companies on the platform: own, partner, or affiliate. An easy way to determine which is appropriate is to use a value curve. First calculate the value of each interaction type on your platform (the average revenue generated per interaction) and then multiply that by the total number of interactions of that type. If the average revenue generated is not available, a simple metric such as monthly average users can be used to denote value. Create a value curve by plotting the value of the interaction types from the greatest to least. A platform should own—by either building or buying—the most valuable or high-frequency interactions at the head of the value curve. That allows it to maintain full control over the architecture, governance rules, and user data. A platform should partner with companies whose interactions fall into the middle of the value curve, sharing control over the architecture, governance, and data. A platform should let third parties become affiliates when their interactions fall on the tail of the value curve.

Although affiliates may provide less value, they serve as fertile ground for experiments that can mature into partner opportunities. Tencent used this approach by elevating Meituan and Pinduoduo—both initially tail interactions on its platform—to partner status as they gained momentum. Pinduoduo later launched Temu, which found international success in a space where Tencent had struggled. This opened up an untapped growth pathway for Tencent. Using the own-partner-affiliate strategy, Tencent has effectively grown its market value from $8 billion to $400 billion in just 12 years. (See the exhibit “Tencent’s Value Curve.”)

Similarly, enterprise software companies like ServiceNow and Salesforce used value curve logic to expand their platforms. Both firms integrated developer tools, APIs, and app stores into their software, enabling developer affiliates—often their own customers—to sell enhancements directly through their platform app exchanges. For high-value interactions, both companies built or acquired key assets (for example, Salesforce acquired Data.com and Slack). They partnered with widely used apps, developing deep integration with them; for third parties whose tools generated the least valuable interactions they simply listed the offerings in their app stores. This strategy led to a $5.9 billion valuation of ServiceNow’s app store and a $22 billion valuation of Salesforce’s AppExchange.

Define a Compelling Theme

By focusing solely on core interactions, platform managers overlook other potential avenues of growth. Instead, they should strive to define a compelling theme for expansion in which platform interactions relate to one another in a coherent logic. Compare Groupon in the United States with Meituan in China. Both began as group-buying platforms that pooled customer demand to drive volume discounts for local purchases, with Groupon launching two years ahead of Meituan. Yet Meituan aimed high with a broad but coherent theme of providing local goods and services and on-demand delivery. It expanded from group buying into food delivery, groceries, wholesale supplies, bike sharing, entertainment, and travel. It bought Dianping, the Chinese equivalent of Yelp, so that users could evaluate their purchases through feedback and reviews, and it used Dianping’s data to promote desirable, new local offerings on its platform. Meituan achieved significant growth by repeatedly adding sides and interactions that aligned with its broad theme. It succeeded in cultivating new merchants that attracted new consumers; at the same time the growing number of consumers attracted new merchants. Meituan built a spiral of network effects in ways that Groupon never managed. Consequently, Meituan’s per-user engagement is now at least four times higher than Groupon’s, and its market value is 150 times greater.

Platform owners should start by establishing a theme that is broad enough to contain many growth options. Meituan’s focus on local on-demand delivery and entertainment is a much larger space, with many more growth opportunities, than just group buying. Uber’s travel and delivery theme is broader than taxi service.

Repeatedly employing the four growth mechanisms can lead a platform to become a “super app”—a platform that provides a single point of access to a multitude of related interactions, as Uber is doing with transportation. China’s Lianjia created a super app that combined a real estate marketplace with services like renovation, maintenance, and mortgages—essentially merging the offerings of Zillow, Redfin, Angi, and Rocket Mortgage. In the United States, there are many opportunities for theme-based super apps: For example, a car services super app could offer vehicle purchases, financing, insurance, maintenance, and repairs. A dating app could integrate matching with relationship advice, beauty services, event bookings, and safety verification.

While platforms begin with a theme, some evolve into super app conglomerates, extending far beyond their origins. WeChat grew from a social media site into a broad marketplace of goods and services, and Indonesia’s Gojek expanded from delivery services into ride hailing, healthcare, and entertainment. These super apps have thrived by embracing a theme of variety and convenience—a one-stop-shopping experience enabled by central navigation, messaging, and payment systems. As they expand, they maintain control over messaging and payments utilized by other interactions on the platform, thereby facilitating cross-platform network effects.

. . .

When seeking growth, platform owners often overlook opportunities right in front of them. By defining a clear vision and leveraging the techniques we have described to expand sides and interactions, companies can unlock significant growth potential.

A version of this article appeared in the May–June 2025 issue of Harvard Business Review.

David J. Bryce is an associate professor of strategic management at Brigham Young University’s Marriott School of Business.

Jeff Dyer is the Horace Beesley Professor of Strategy at BYU’s Marriott School of Management. He is the lead author of the best-selling book The Innovator’s DNA and coauthor of The Innovator’s Method.

Marshall W. Van Alstyne is the Allen & Kelli Questrom Professor of Information Systems at Boston University.