Golda Meir’s Persistence

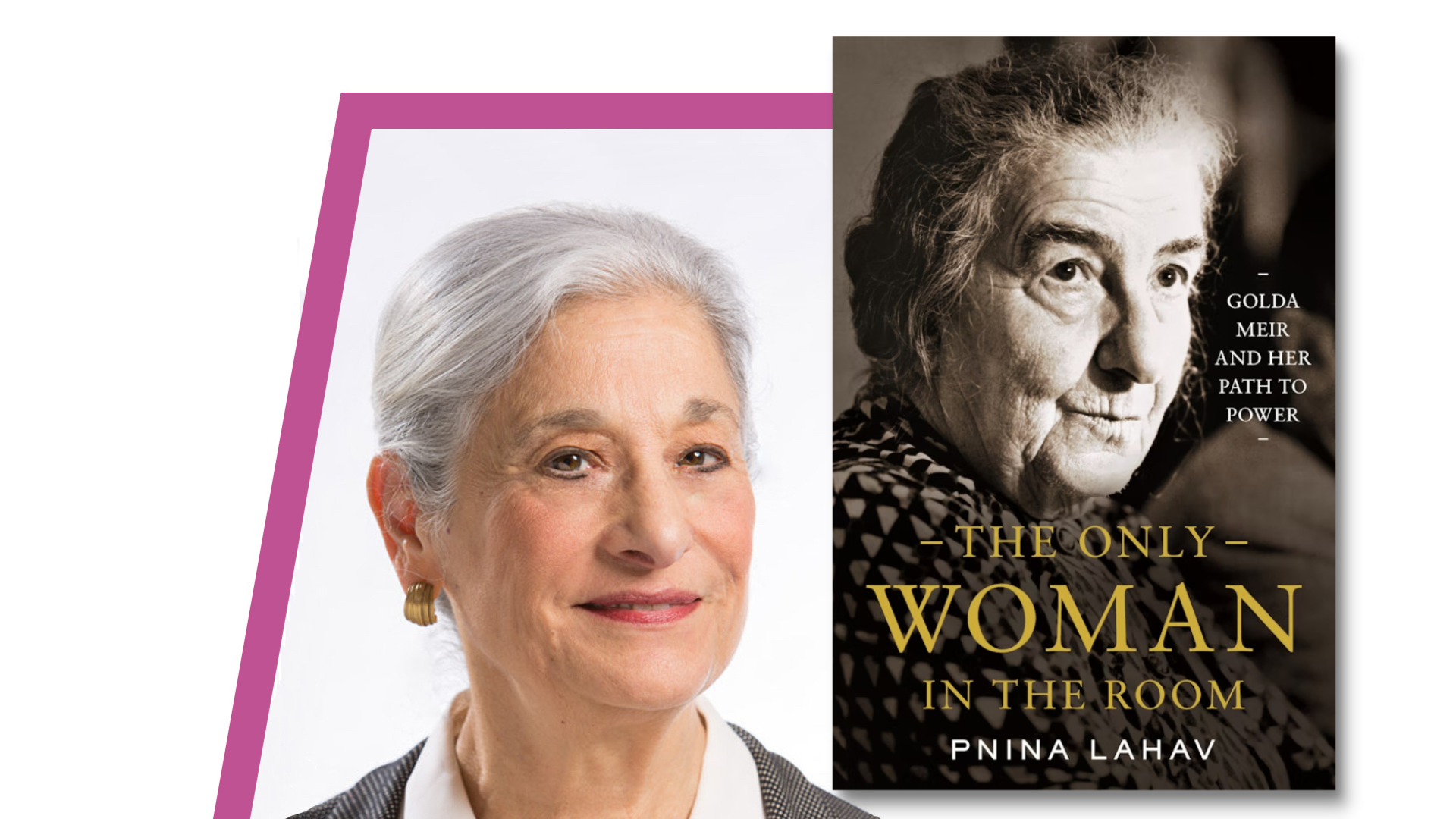

BU Law Professor Emeritus Pnina Lahav examines the Israeli leader’s life with a feminist lens.

Golda Meir’s Persistence

Professor Emerita Pnina Lahav examines the Israeli leader’s life through a feminist lens.

In February, The Record spoke with BU Law Professor Emerita Pnina Lahav, about her recently published book, The Only Woman in the Room: Golda Meir and Her Path to Power (Princeton University Press 2022), a biography of Israel’s only woman prime minister from a feminist perspective.

Golda Meir was born in 1898 in Kyiv when it was part of the Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine). Her family immigrated to the state of Wisconsin when she was eight years old. Meir started her career as a Yiddish teacher in Wisconsin. Prompted by their Zionist ideology, she and her husband moved to Israel in 1921. There, she moved up the political ladder and served as labor minister and foreign minister before being elected prime minister from 1969 through 1974. She was Israel’s fourth prime minister and, so far, only woman to serve in the role.

Listen to an unabridged version of the interview:

Q&A

The Record: How did your interest in exploring Golda Meir’s life begin?

I grew up in Israel and went to an Israeli law school, where they had either never heard about feminism, or didn’t like it. I went on to do my graduate work at Yale Law School, where feminism was flourishing. Yale offered the first courses on women in the law. I was drinking it all in and realizing how thirsty I had been to understand the status of women in society.

As this experience was dawning on me, I wanted to research this myth, which I think still exists today, that in Israel women are treated equally to men. People always like to make examples of the fact that Israeli women serve in the military and that Golda Meir had been prime minister.

So, I looked into the status of women in Israel. Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was a professor at Columbia Law School at that time, helped me publish an article on the subject in the American Journal of Comparative Law.

I went on to teach at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where my colleagues were not enthusiastic about my ideas on women’s equality. As a result, which happens to many women, I abandoned my scholarly interest in feminism. I focused on topics that are always popular, such as national security, freedom of expression, and various aspects of the First Amendment. I developed a great interest in war, which has been a male-oriented kind of work. I did it for survival, as I understood that women who devote their lives to feminism do not fare well.

Recently, the time came to retire, and I decided that I wanted to present women in both Israeli history and American history who represented the perseverance in feminism. I chose Golda because she reached the height of political power in Israel, but also because she had an American background.

The Record: When researching for the book, was there anything that surprised you?

What surprised me particularly was how strong she was, how many attacks she had to absorb. People sometimes vilified Golda, talking about her as an old woman, as an ugly woman, focusing on the way she dressed.

I was surprised to see the level of intensity, which is basically anti-woman. Thoughtful journalists would fall into this description of “Golda is overly emotional.” Then, on the other hand, they would say, “she’s so tough.” They were not even aware of the fact that they were contradictory in their analyses.

I collected many statements about her from the press, from Knesset [Israeli parliament] deliberations, that are misogynist. And I used them to show the climate in which she was operating and thriving. Despite this antagonism, she persevered. And that’s the lesson to women, you can and should persevere.

The Record: There have been many takes on Meir’s life, but your feminist lens required that you depict some of her experience through speculation.

Can you share with us what the process was like in finding ways to relate to your subject?

Some of the reviews criticized me for speculating. But how can you write a biography without speculating? I could not interview her, because she was dead. She left very few letters and few documents discussed her motivations or state of mind. The problem is Golda never wrote. I think she was a little bit insecure about writing, and therefore stayed away from it. So you don’t have letters that say, “here is how I felt, here is why I decided to do what I did.” You have to rely on your common sense. Put yourself in her shoes.

All biographical work is speculative. You don’t know exactly what the person thought. The reader should decide if your interpretation is valid.

I collected many statements about her from the press, from Knesset [Israeli parliament] deliberations, that are misogynist. And I used them to show the climate in which she was operating and thriving. Despite this antagonism, she persevered. And that’s the lesson to women, you can and should persevere.

Golda wants power, not for the sake of power, but because she’s driven by social ideas and ideals that she’s trying to pursue. Every woman who aspires to take a position of leadership and decision-making—that requires power—would encounter misogyny and must persevere.

The Record: The waves of feminism may differ a bit between the US and other parts of the world. For instance, as Meir became a leader in Israeli politics in the 1950s and 1960s, the US was transitioning to second-wave feminism.

However, it is said that Israel may not have reached that era of the movement until the 1980s. Can you illustrate what the Israeli mindset around feminism was during Meir’s decades of leadership?

Golda was not enthusiastic about the United States second wave feminism in the 1970s, mainly because many of the activists were sympathetic to the Palestinians and hostile to Israel, and she therefore was reluctant to identify with them.

Also, in Israel, similar to the United States, women felt that there was something menacing, unseemly about feminism, and that a woman who insists on her rights is embarking on a wrong path. You may suggest that they feared the challenge to the patriarchy and its consequences.

At the same time, many Israeli women felt there wasn’t anything that they could not do, even though that was not true. If you as a young woman think that you can do anything, you may be disappointed, you may be frustrated… But you believe that you can do it.

Whereas I think in the United States, it was a bit more circumspect. In the 1950s, women went to college; then they were supposed to get married and do well as housewives, mothers.

In Israel, and also because of Golda, the idea was, you can have a career, and at the same time, also have a family and children. That you don’t have to choose. That was the Israeli belief and I myself grew up with this world view.

The Record: How might Golda Meir’s path inspire women leaders, and how might it inform people to act as allies?

Golda was signaling to women: Don’t run away. Don’t feel intimidated. Have confidence in yourselves. Open your mouth and say what you think, and it will work out. You are entitled to fulfill yourself. To say what you think. You have a right to that.

Men, when they look at Golda, should understand that women can do both. You can have children, you can be married, you can even have lovers. And at the same time, you can have a career. It’s not as if you must choose. It’s not a zero-sum game. Compromise is necessary.