Immigrants’ Rights Win for BU Law Clinic & Coalition

A team including the BU Law’s Immigrants’ Rights & Human Trafficking Program passes legislation to protect immigrant survivors.

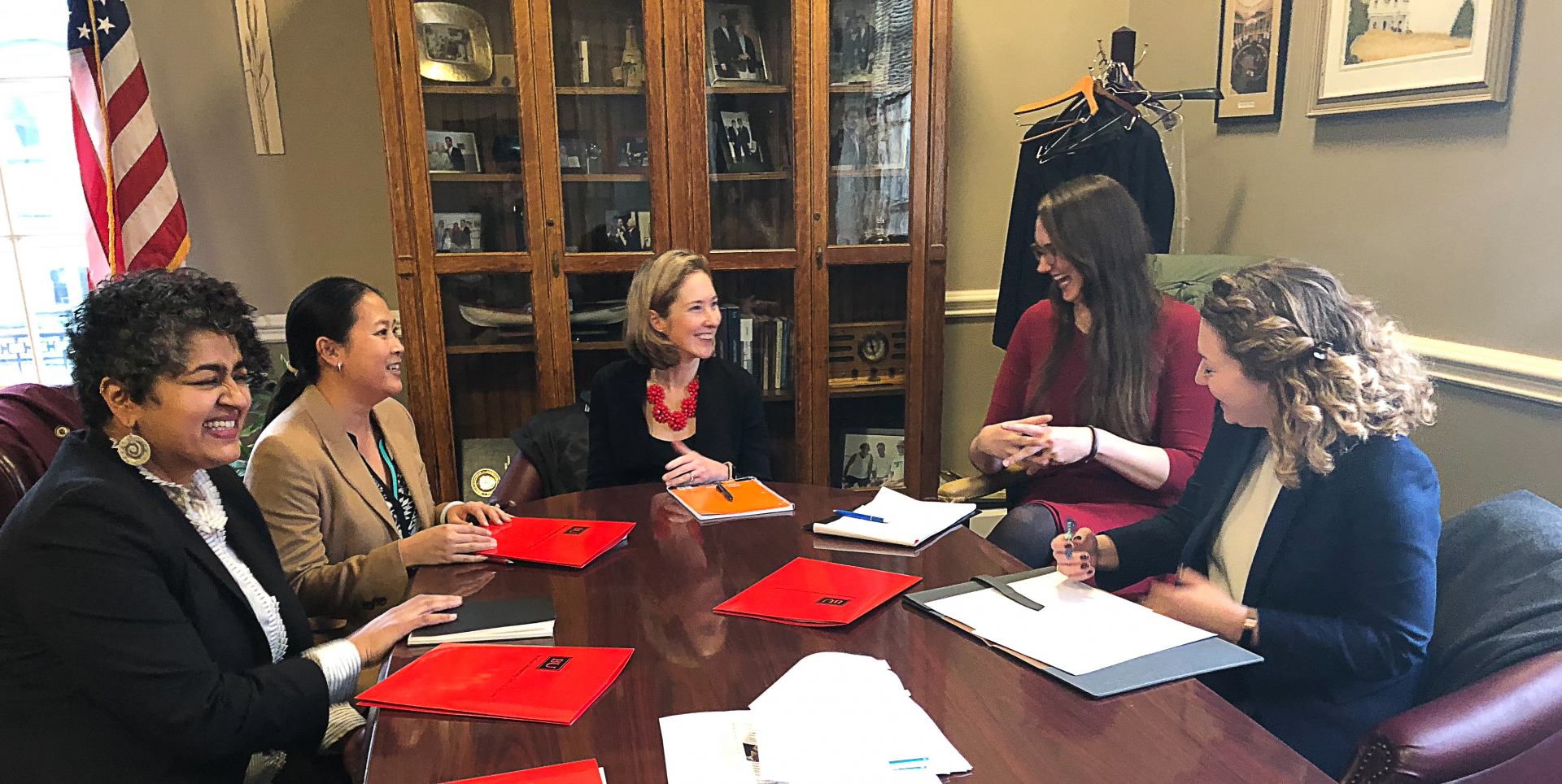

From left to right: Hema Sarang-Sieminski (Jane Doe, Inc.), Emily Leung (Justice Center of Southeast MA), BU Law Professor Julie Dahlstrom, Emmylou Manwill (’20), and Brittany Hacker (LAW’20, GRS’20).

Immigrants’ Rights Win for BU Law Clinic & Coalition

A team including the BU Law’s Immigrants’ Rights & Human Trafficking Program passes legislation to protect immigrant survivors.

When Greselda de Leon’s father lost his job, her life in the Philippines was completely uprooted. She dropped out of school to work full time, but it was not enough income to support the whole family. De Leon moved to the United Arab Emirates to earn more as a domestic worker. “The last thing I wanted was to leave my country, but I felt like I had no choice,” she says.

Soon after, a recruiting agency transported de Leon to Boston on a personal/domestic worker visa. Any semblance of control over her life was now gone: her bosses took her passport, withheld pay, burned her arm in the oven, and dehumanized her.

De Leon managed to escape her abusers but was reluctant to talk to the police. “In the Philippines, the police are often corrupt, and they can’t be trusted,” she explains. De Leon called the National Human Trafficking Resource Center hotline and was connected to the BU Law Immigrants’ Rights & Human Trafficking Program (IRHTP). But prior to the passing of the 2021 Massachusetts Act Promoting Safety for Victims of Violent Crime and Human Trafficking, not all immigrant survivors had the security or resources to report their abusers.

Over two decades ago, Congress passed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act to safeguard immigrant survivors of abuse or trafficking who aided government agencies in investigations of these crimes through U or T visas. These visas prevent deportation, provide an opportunity to work, and set up a pathway to citizenship.

However, the act requires a certification from a law enforcement agency confirming the visa applicant’s assistance with the investigation. “Sometimes agencies didn’t understand what that certification process looked like, they didn’t respond to requests, or if they responded, it took a very long time,” explains Julie Dahlstrom, clinical associate professor and director of the IRHTP.

In the case of de Leon, law enforcement retrieved her passport and belongings, but it took over a year to receive a response to her T visa certification request. “I felt so confused,” she says. “I didn’t understand how this could happen after I told the truth and did my best to help.” This waiting period leaves immigrant survivors vulnerable, unable to seek work or housing assistance without the proper documentation. Additionally, the perpetrator may still attempt to communicate with the survivor—even actively threatening them—as immigration status is often another tool in the cycle of abuse.

For an immigrant who is already facing many uncertainties, the wait and lack of information can be excruciating. And in the cases of U or T visas, they are stuck in unsafe home or work environments. “Any place where you can add a little bit of clarity and transparency about the possibilities helps immigrants’ willingness to step forward as participants in the process with law enforcement,” says Emily Leung (LAW’07, GRS’08), supervising immigration attorney at the Justice Center of Southeast Massachusetts.

Dahlstrom and Leung noticed other states had passed bills to improve the U and T visa certification process, and in 2016, they began researching how to bring similar solutions to Massachusetts.

By September 2017, they began translating their ideas into a bill. The team expanded to include students in Dahlstrom’s clinic; partnerships with local immigration agencies, including the Mass Law Reform Institute; legislators, including Senator Mark Montigny, Representative Tram Nguyen, and Representative Patricia Haddad; and Attorney General Maura Healey. Over the next four years, the coalition focused on drafting the bill, engaging with legislators, leveraging partnerships with agencies such as the Massachusetts Office for Victim Assistance, and advocating to constituents with carefully crafted messaging.

Julie Dahlstrom and students from her Immigrants’ Rights & Human Trafficking Program were vital in this effort, and I commend their ongoing work to support survivors, combat crimes against immigrants, and help build trust with law enforcement.”

As key team members, students in the IRHTP contributed to the research, strategy, and constituent advocacy. One of Dahlstrom’s students, Abigail Alfaro (’21), focused on the framing of the bill. She explains, “It’s both an access-to-justice issue and it assists law enforcement. We designed our materials for the coalition and for legislators related to that, highlighting the core key reasons why it should be passed.” Alfaro and the team intentionally used the preferred language of the immigrants affected by these issues. One client, Catherine Piedad, explains, “I call myself a ‘survivor’ not a victim. I went through some very difficult things in my life, but my life is so much better.” Representing the survivors with empowering language in the bill materials also signals to the survivors that law enforcement may be sympathetic, and could help build trusting relationships.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges in passing the bill with delays in government office responses and the learning curve of virtual advocacy relationship building. However, the public health crisis directly demonstrated the need for the bill. Agencies saw an 8.1 percent increase in domestic violence incidents following lockdown, and the pandemic made more apparent the racial inequities that leave people of color more vulnerable due to poverty and poor health. Sex and labor traffickers take advantage of economic need to lure in workers.

As the bill made its way through legislative sessions, Dahlstrom and survivors like de Leon shared testimonials. The bill was attached to the Massachusetts fiscal year 2022 budget and passed early in the second legislative session, a remarkable success, given the limitations of the pandemic and the legislative processes, proving the strong network of supporters the coalition built. “This was an effort that was undertaken by many people,” Leung says. “This victory belongs to a lot of folks.”

“This new provision encourages immigrants to report crimes against them and ensures visa certification requests by survivors of domestic violence, sex or labor trafficking, and other qualifying crimes are processed quickly and efficiently to help them build a life in this country,” says Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey. “Julie Dahlstrom and students from her Immigrants’ Rights & Human Trafficking Program were vital in this effort, and I commend their ongoing work to support survivors, combat crimes against immigrants, and help build trust with law enforcement.”

As part of the implementation of the bill, agencies are required to establish an explicit policy about how their office approaches U and T visas. They must also report on the volume of requests for visas, as well as the rate of denials. An annual public report will ensure accountability. Dahlstrom says, “There have never been statistics about these certifications, the number that are requested or issued in these different offices.” The coalition hopes the data will indicate where there is need for more education and advocacy.

Griselda de Leon has continued building her life in the US with a stable job and is raising her child as a US citizen. “Now, I am living my dream,” she says. “I want to give others this chance too. I want them to know that they can come out of the shadows and speak out if they are abused. They can have freedom too. And they can trust that our government will protect them.”