Telepractice Presents a Challenge to Voice Therapy

Boston University researchers urge caution when evaluating voice disorders over teleconferencing platforms due to differences in acoustic measurements.

BY GINA MANTICA, gmantica@bu.edu

Over the past year, people across the world learned how teleconferencing platforms like Zoom can help folks stay connected – playing games with friends, hosting virtual weddings, and even visiting a doctor. But voice therapy presents a unique challenge in a virtual world. Clinicians rely on acoustic recordings of voice to evaluate the effectiveness of their treatments, and many teleconferencing platforms distort sounds in their efforts to eliminate background noise.

Hasini Weerathunge, a Graduate Student Fellow at the Hariri Institute and a PhD candidate in Biomedical Engineering, worked in the lab of Research Fellow Cara Stepp, a Professor at BU College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College, to investigate whether HIPAA-compliant teleconferencing platforms could capture sounds accurately enough for voice therapy evaluations in patients with voice and speech disorders. The research was recently published in the Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research.

Voice therapists conducted telepractice sessions with patients before the pandemic, but the studies examining the effectiveness of treatment were all carried out in person – the accuracy of their evaluation procedure has never been examined online. Typically, a patient goes into the lab for their treatment evaluations and sits in a sound-proof booth outfitted for speech recordings. The patient repeats sustained vowel sounds, like “aaa” or “ooo”, or reads the “rainbow passage” – a short passage about the science and history of rainbows that reflects a wide variety of sounds and mouth movements in the English language. The recordings of the patient’s voice are then evaluated by algorithms that measure acoustic properties, including the acoustic correlates of perceived pitch and loudness of the voice.

These in-person evaluations stopped last year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Weerathunge saw an opportunity to help the voice therapy community by investigating which telepractice platform is best for these sorts of evaluations. “There was no consensus among clinicians trying to convert to telepractice therapy, and we wanted to determine the accuracy of the acoustic measures they can get through telepractice,” she said.

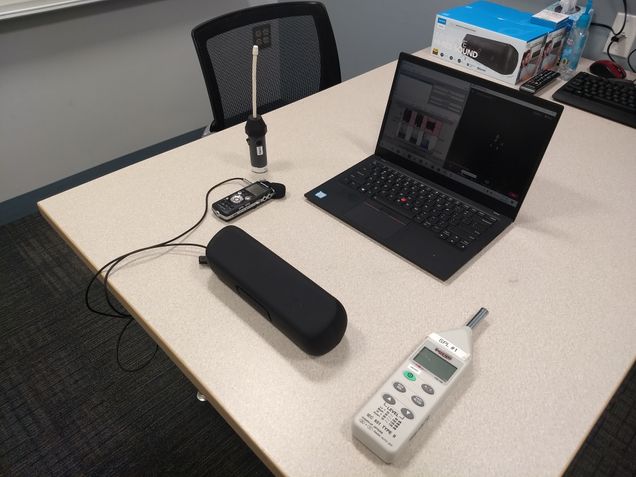

Weerathunge and a team of Boston University researchers put five different HIPAA-compliant teleconferencing platforms to the test: Cisco WebEx, Microsoft Teams, Doxy.me, VSee Messenger, and Zoom. The team recorded voice samples from 29 patients aged 18-82 years old that had a variety of speech or voice diagnoses in a soundproof room. These recordings were then played back through an external speaker over the teleconferencing platforms to researchers, simulating telepractice conversations.

The team quickly learned that each platform has its own audio enhancement algorithm that affects the quality of the sound. Zoom was the only platform that enabled users to turn off these audio enhancement features, allowing the researchers to test the platform’s original audio.

Despite the sound oddities, the researchers predicted that the standard measures of vocal fundamental frequency (i.e., the acoustic correlate of pitch) and vocal intensity (i.e., the acoustic correlate of loudness) would not be significantly affected. “No matter how much noise is added to a recording, you should still be able to measure the mean values of acoustic correlates of pitch and loudness,” said Weerathunge. In line with their hypothesis, the team found that measures of the mean vocal fundamental frequency were not statistically significantly affected by teleconferencing platforms.

However, Weerathunge discovered that all the teleconferencing platforms did a poor job at capturing many of the other measurements needed for accurate and clinically meaningful voice evaluations. “Microsoft Teams performed the best, in that all our voice measures were the least affected in that platform,” said Weerathunge. But the vocal fundamental frequency varied significantly on all the virtual platforms compared to the real-life recordings. This might be due to Internet connection or bandwidth issues that affect how and when sounds get transmitted through the platforms.

Surprisingly, the dynamic range of the vocal intensity measured over telepractice was very different from live recordings. “This was the biggest surprise for us,” said Weerathunge, “The platforms’ audio enhancements changed the amplitude of the signal.” This was true even in Zoom, where the researchers could turn off the audio enhancements.

Because many of the voice metrics collected from virtual platforms had clinically significant differences from those collected in person, Weerathunge and team urge clinicians using telepractice to exert caution. The researchers recommend that patients record their evaluations ahead of time rather than doing the evaluations over telepractice, or that clinicians remain flexible with what measures they use to evaluate patients. “Although the COVID-19 crisis appears to be waning, telepractice popularity is here to stay,” said Stepp, “This work is likely to have substantial impact on clinical practice, providing crucial information about the effects of these telepractice platforms on clinical voice evaluations.”

This work was supported by grant R01 DC015570 from the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, COVID-19 pilot grant UL1 TR001430 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences via Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute, and a Graduate Student Fellowship from the Rafik B. Hariri Institute for Computing and Computational Science and Engineering.