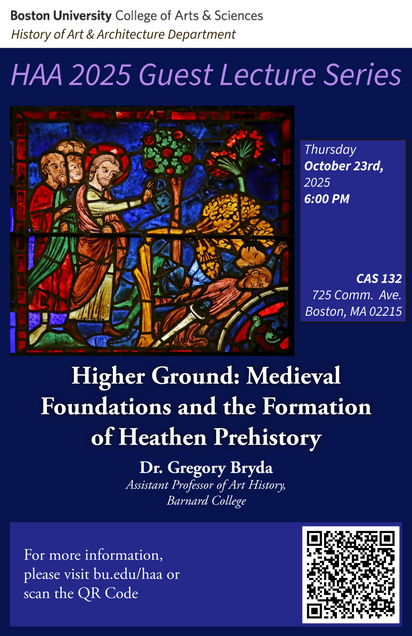

HAA Fall 2025 Guest Lecture Series

This talk argues that in the Middle Ages, Christians used art to exaggerate a pagan affinity with the land to invent a false contrast, which enabled a redefinition of the landscape through a Christian lens. From the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries, as Christianity spread eastward across northern Europe in successive waves, artworks in wood sculpture, monumental stone carving, manuscript illumination, panel painting, and woodcut consistently portrayed non-Christian peoples as nature-bound idolaters—tree-worshippers, grove-dwellers, keepers of wells and stones. Scholars have long mined these representations for traces of authentic pagan ritual, frequently construing them as proof of syncretism in the process of conversion. I contend that the artworks portray retrospective fictions. Produced after Christianity had taken root, these works were directed less at pagans than at other Christians. By portraying a primitive “other” bound to earth and nature, ecclesiastical communities of various stripes—parish churches, cathedral chapters, Cistercian monks, Teutonic Order knights—cast themselves as its opposite: orthodox, rational, divinely sanctioned. In doing so, they justified their authority, sharpened rivalries, and claimed stewardship over the land as a sacred trust. What has been read as proof of confrontation thus emerges instead as self-reflective, with patrons deploying the arts to reshape both the perception and the use of land to align with their own specific needs.

To view an archive of past lectures and find details about upcoming events in the series, visit our HAA Lecture Series page.