BU Faculty on How They’re Faring with Learn from Anywhere

Saida Grundy, a CAS assistant professor of sociology, teaching her Race, Class and Gender course from the “cockpit” in her home September 29.

BU Faculty on How They’re Faring with Learn from Anywhere

They talk candidly about the pros, the cons, and the progress they’re making

In March, when the spread of coronavirus forced BU to cancel in-person classes, in a matter of days faculty were told to start teaching remotely. It was a trial by fire, and it worked, sometimes well, sometimes not so well, but always with the full determination of a faculty that put teaching and learning first.

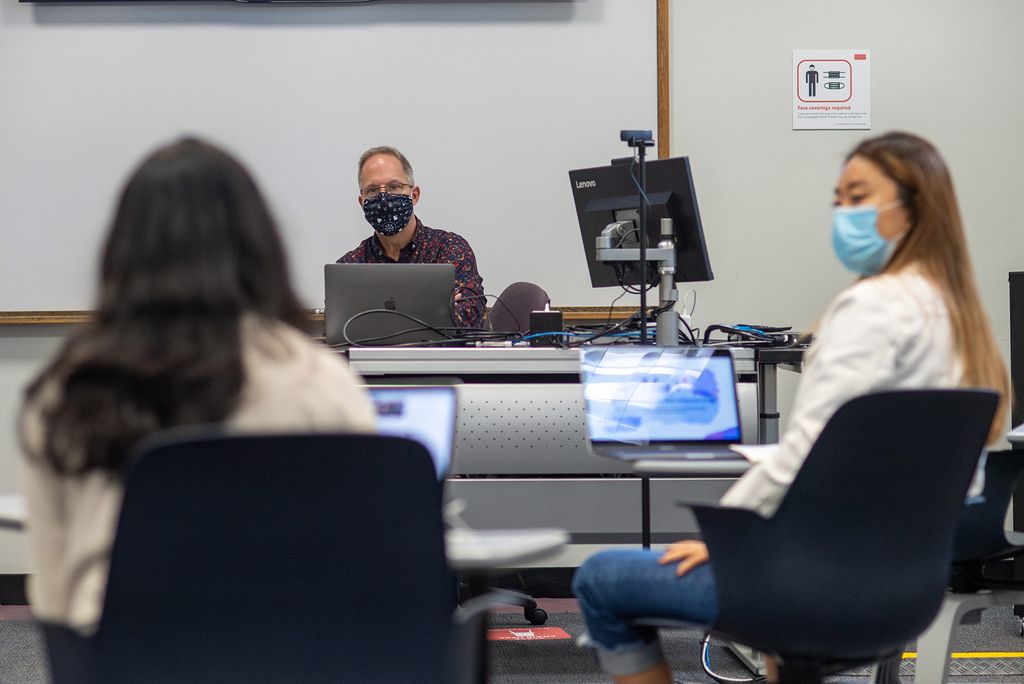

Three weeks later, when some faculty members were still grappling with how to display documents in Zoom, the University’s Undergraduate and Graduate Working Groups began to formulate a clear longer term plan, one that could carry BU through the fall semester, if that were necessary, and even longer, if that also proved necessary. Their solution was Learn from Anywhere (LfA) a hybrid format that gives students the choice of taking classes in person or remotely. To the distress of many faculty members, LfA required most of them to teach in-person classes, although the number of students in those classes would be greatly reduced to comply with social distancing protocols. Similar hybrid formats have been adopted by more than 600 of the 2,958 colleges and universities tracked by Davidson College’s College Crisis Initiative (C2i) dashboard.

Now, with five weeks of LfA under their belts, how are faculty faring? The answer depends on who you ask, and opinions appear to be dominated by three concerns: the technology can be challenging, the emotional connection with students is hampered, and despite BU’s extremely low rates of positive test results for COVID-19, there is some anxiety about the transmission of the virus. There are also some bright spots: many faculty members are glad to be back in the classroom with students, the technology offers some welcome conveniences, and there is a sense of progress as faculty become more familiar with the technology.

“This semester is when the saying, Never let them see you sweat, comes to mind,” says Alice Tseng, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of history of art and architecture. “Each time I’m in the classroom—wrestling with room technology, offering my full attention to the students in the room and the students on Zoom, breathing hard through the mask, speaking into two different microphones, looking into two different cameras while keeping eye contact with students in the room, and minding that I do not touch any surfaces that have not been properly disinfected—I must simultaneously appear calm and in control so that students are learning the best they can from me.”

And, Tseng notes, many faculty—herself included—remain very concerned about virus transmission. A number of her students have told her they don’t feel comfortable attending in-person classes as well, for fear of contracting the virus.

Teaching in-person classes was initially unnerving for Susan Mizruchi, William Arrowsmith Professor in the Humanities, a CAS professor of English, and Center for the Humanities director. “Like everyone else,” Mizruchi says, “I was afraid of getting sick, but I think we need to give credit where credit is due. The University, in contrast to many across the country, has put a lot of effort into establishing a system capable of keeping us relatively safe.”

Speaking of LfA in general, Mizruchi says she’s encouraged by the progress she’s made, much of it with help from IT staff and a classroom moderator. “I was certainly intimidated by the prospect of hybrid teaching,” she says. “But the fact that I was given a moderator to help me manage remote students as well as my film and TV streaming made all the difference. My gratitude for that is endless.”

Which isn’t to say that technology hasn’t presented some bumps. In her first two classes, she lost about 15 minutes trying to get the microphone working properly. “Now things are working much better,” she says. “I’ve found the IT people extremely responsive to the many challenges that arise. They’ve been fixing things as we go along. All of this has really been a work in progress.”

She says her course The Myth of the Family: from Huckleberry Finn to Breaking Bad normally closes at 62 students, but she was advised to hold it to 56 this semester so it could be divided into two groups that would each fit in a space that can accommodate up to 22 students. At any one time, she has about 40 students on Zoom.

“Remote learning is alienating,” she says, “but there are ways to get beyond that. Is it working? Yes, but do I want to do this for the rest of my life? God, no. I want to be back in class with all my students, as we all do.”

Doug Gould, a College of Communication professor of the practice of advertising, is teaching two small classes this semester, one with 15 students, one with 18. He is also a faculty advisor to COM’s AdLab, which has 120 students and meets at the George Sherman Union. In his two smaller classes, about 40 percent of the students are in person.

“I think the University protocol is excellent,” he says. “As a 57-year-old faculty member, I don’t come into school worried about catching the virus, because the protocol is tight, but I do come to school worried about my ability to do a good job teaching.”

His main concern, especially in his smaller, more intimate classes, is the development of personal relationships. “That is something that’s very difficult with a mask on,” he says. “When you wear a mask, you take away one half of the face, and it’s a critical half. It’s the half that smiles, and the half that shows concern, and the half that says, ‘Nice job.’”

“Every teacher wants to build a relationship with the entire class,” Gould say. “But if there are live students in front of you, those are the people you’re going to look at. The screen doesn’t really exist until someone raises their hand or says something in chat. You are constantly trying to toggle back and forth between the live people and the remote, and that affects your ability to have a cogent thought.”

But, he says, “the good thing about all this is that students get to experience their education in a way that represents something close to what they were hoping to get.”

“My first class was like, ahh, this is awkward,” says Saida Grundy, a CAS assistant professor of sociology and of African American studies, who believes she is “off to a fairly good start” teaching remotely, while continuing to feel out the best way to handle in-person classes. “I found out that the students warm up to you, and if your personality can come through the technology, it works well. I never expected that.”

Grundy says LfA has revealed some “small silver linings” to teaching remotely. “If remote teaching forces us to use platforms of classroom management that we should have been using the whole time, that’s a plus,” she says. “There is no reason we didn’t have direct messaging with students before this. Also, with remote, my students have a digital community that makes working on group projects easy, and it’s easier to continue a remote class than an in-person class. When I get off a session of my remote classroom and Microsoft gives me notification that my class has been recorded and uploaded to the cloud, I can go and link to things that I was talking about. I can supplement so much more easily—it’s like the classroom environment is 24 hours. For some professors, being accessed 24 hours a day can be a nightmare, but there are ways you can put boundaries around it.”

But how does someone teach a hands-on course like painting to both in-person and remote students? Jill Grimes is finding out. A College of Fine Arts senior lecturer in art and painting, she is teaching two undergraduate painting courses—both hybrid—with roughly a third of the class remote. Grimes has adapted her teaching method to present projects and video demonstrations remotely, while students upload photos of their works in progress, to be reviewed both individually and in group discussions on Zoom.

For remote students, she says, working from models or still life setups can be difficult, so she has integrated projects based on contemporary and historical models into the curriculum. While acknowledging that it’s hard to fully appreciate a painting by looking at a digital image, it does work, she says. “Teaching painting really requires students to gain experience with…paint. And painting requires a place to work, ideally with ventilation, no roommates or family to complain. Figuring out how to be flexible enough to challenge and educate the students that have paint and a place to work,” she says, “along with students that are in isolation, with little or no materials, requires adjusting assignments to fit individual circumstances for some students.”

Logistics are a challenge because of the protocols, Grimes says, “but as everything is right now, we just have to work with it.” The most encouraging thing, she says, has been the response of her students. “Students are natural problem solvers. Their attitude toward this shift to remote and hybrid models reflects their resilience and determination to continue their educational path. Their energy inspires me to make these courses work.”

Stephen Scully, a CAS professor of classical studies, has also been impressed with his students’ efforts to make LfA work. “Students have been compliant, patient, accommodating, and earnest in their studies,” he says. “And IT has been helpful, if understaffed.”

That’s the good news. As department chair, says Scully, what he’s heard from many faculty members paints a darker picture. “Faculty from across CAS have described the LfA model to me as close to impossible,” he says. “It tries to do two things at once, but ends up doing both poorly or not at all.”

A note from one faculty member reported some inspiring moments. “But,” the note also said, “I’ve never felt the pleasure of teaching sapped more than I have this year.”

Some faculty, Scully says, think the hybrid format is more stressful than classes that are either taught completely in person or completely online. Some have told him that they would prefer to reserve the LfA model for the specific classes it works for, and otherwise bolster a model that allows students to choose between fully in-person and fully remote classes.

But he has been impressed with how seriously the BU community has responded to the crisis. “Positive tests are impressively low,” he says. “The administration has to be commended for its unflinching commitment to testing, mask-wearing, social distancing, and other precautionary measures, and the students have to be commended for their compliance.”

Overall, Mark Crovella, a CAS professor of computer science, supports the administration’s decision to adopt LfA. “I don’t see a better option, all things considered,” he says, “but there have been some surprises.

This semester, he’s teaching a class of 90 students in a classroom where social distancing limits the number of in-person students to 21, but he has yet to have more than 5 in person for any lecture. “I get it. There are lots of reasons not to come to a lecture in this environment, but I just assumed there would be more than that,” he says. The surprisingly low in-person attendance “means that I don’t have any concern about the classroom being a major locus of viral spreading, but it also means that the strategy of “going remote” for a few weeks that some schools have taken in response to outbreaks wouldn’t have much effect here—there are not enough students in the classroom for it to matter.”

Crovella says he can’t get over the technology that’s been put in place to make LfA work. “I am blown away by the effort the University went to over the summer to equip classrooms. I went in to test the day before my first lecture and the technology, basically, just worked—but that doesn’t mean it’s simple.” He now arrives at class 10 minutes earlier than he used to just to get the technology ready to go. “I can set up a laptop for hosting Zoom and connecting to classroom AV, a tablet for showing slides and making hand annotations, a room projector, earbuds with microphone, connecting and enabling the in-class moderator in the Zoom session, making sure the moderator’s headset and microphone connections are working, and making sure all the other physical and logical connections are made just right,” he says.

“As long as you don’t forget anything, it works great!”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.