Nuclear Governance Class Offers Context to Current Headlines

Explores scientific, political, historical, and anthropological angles to these weapons

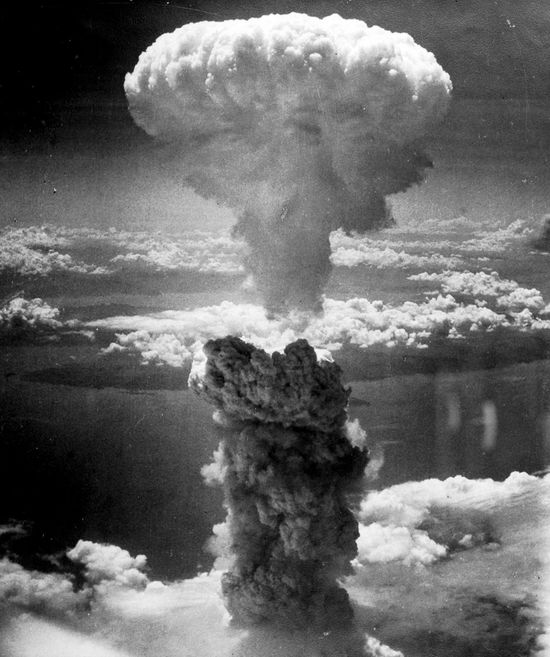

North Korea’s nuclear arms drive, reflected in this recent missile test, is among the challenges studied in a BU class on controlling nukes. Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP, File

Class by class, lecture by lecture, question asked by question answered, an education is built. This is one of a series of visits to one class, on one day, in search of those building blocks at BU.

Will Kim Jong-un (aka “Rocket Man”) blow up half the world with his nuclear arsenal? Will the US president thwart him as part of his grand design to make America great again?

This may sound like a breathless TV cliffhanger, but it’s actually based on the last year or so of headlines, describing the sometimes-hot rhetoric aimed at stopping cold North Korea’s nuclear program. Students in Jayita Sarkar’s Nuclear Governance class recently grappled with this unnerving reality, pondering possible parallels between Kim’s regime and Iraq—which was forced to dismantle its nuclear weapons program after the 1991 Gulf War—and Libya, which voluntarily surrendered its nukes in 2003 in a deal with the George W. Bush administration.

In a class where the assignments include “policy memos,” you’d be forgiven for thinking you’d stumbled into a UN Security Council meeting, as many in the roughly 30-student class animatedly offer their viewpoints.

Typical was Alhassan Hashad (CAS’20), who thinks Libya is no model, having “had way less allies” than Kim, supported as he is by Russia and China. “In addition, there were many strong US allies that were directly affected by this. You had Israel and European countries, which were right across the sea.”

In an interview, Sarkar, a Pardee School of Global Studies assistant professor of international relations, notes that the course theme—“We’re talking about mass annihilation”—could scour some holiday cheer during Christmas break. Yet some students find that the class actually douses their news-inflamed anxiety.

“I thought maybe it would make me less scared if I knew what was going on,” says Lorena Villatoro (CAS’20). It worked, the international relations major says: “I really did think that countries could just do whatever they wanted and could just build nukes. And there are a lot of sanctions” if they do, she’s discovered taking the class. “Even though some countries don’t follow them, obviously…there are a lot of repercussions if they don’t adhere to it. That is comforting to know.”

(On the other hand, the class also studied Iran. Six months after the United States withdrew from the nuclear deal with that nation, Villatoro says, it—and the United States—have replaced North Korea as the biggest disturbers of her sleep.)

Thanks to the course’s topicality, Sarkar says, “I don’t have to worry about how do I make it relevant. It’s already relevant; they want to know.” But they may not know how much they need to know. There are scientific, political, historical, and anthropological angles to nuclear weapons, requiring students to “dabble in multiple disciplines,” she says. (The syllabus included topics like “Nuclear 101: How Do Nuclear Weapons Work?” during the opening weeks.)

She developed the class last year with financial support from the Stanton Foundation, whose portfolio includes nuclear security studies, and it covers close calls to Armageddon, such as the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Still, the US bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end the Second World War remain the only use of the atomic bomb since its invention. From this history, Sarkar wants her students to extract several key lessons.

One is that unsung efforts by individuals who kept their wits about them at do-or-die moments has kept that 1945 use unique. During the Cuban crisis, for instance, a Soviet sub officer overrode a fire-torpedo order at US ships. It’s a cautionary tale in how to regard opponents “who’ve been demonized, because that’s how crisis works,” Sarkar says.

Second lesson: managing risks, such as nuclear proliferation, including terrorists acquiring nuclear material, is critical. She says some students shrug that we didn’t blow up the world during the Cold War; she tells them that the country’s still here for them to take her class because of deliberate institutional efforts to limit the spread of nukes, such as intelligence cooperation among allies.

Third lesson: occupational hazards of working with nuclear technology, including peaceful use of nuclear energy, are not always part of the political discussion. Sarkar points to one such risk, radioactive poisoning, as a reminder of how even the most non-martial intentions with this dangerous technology can go lethally awry.

These lessons are more than many students knew going in. “I honestly knew the bare minimum, the things that you read in headlines,” says Villatoro. “It can be very dry at times, but…it’s so relevant. Even it if it’s dry, it’s like, this is what’s happening now.”

This Series

Also in

One Class, One Day

-

February 27, 2019

A Class That Explores the Gospel According to Tupac Shakur

-

October 31, 2018

Trump and the Press: We’ve Been Here Before

-

August 3, 2018

A Scholarly Take on Superheroes

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.