Looking at Children’s Lit in a New Way

Class plumbs classics for adult themes like economic inequality, power

Class by class, lecture by lecture, question asked by question answered, an education is built. This is one of a series of visits to one class, on one day, in search of those building blocks at BU.

The course title is straightforward enough—Children’s Literature: Fairy Tales, Fantasy, and Imaginary Spaces. Then instructor Anna Henchman chalks up the blackboard with discussion topics like ECONOMIC INEQUALITY and POWER + FORMS OF POWER.

Toto, we’re not in the Kansas of traditional story time anymore.

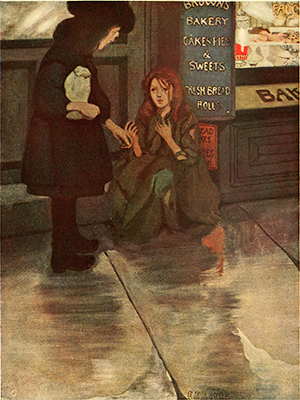

That opinion is confirmed as the class begins hashing out the day’s assignment, A Little Princess, the 1905 novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett about a rich boarding school student who is reduced to penury and a job as a servant. Henchman, a College of Arts & Sciences associate professor of English, zeroes in on scenes where Sara, the heroine, is repulsed by rats in her dingy attic room, only to shed her fear through imagination and empathy. She pretends that she and the rodents are prisoners in the Bastille during the French Revolution—and realizes that she’s looked down on the rats in the same way that adults look down on her in her poverty, one student notes.

Insights effervesce from all corners of the 34-student class regarding Sara’s reaction to her changed economic circumstances: “Things happen to people by accident.” “It’s not really an accident she finally recovers her wealth. It’s what goes around comes around.” “Money isn’t innately good or bad.…People are good and bad, and money can bring that out.”

Henchman enthusiastically conducts the dialogue, noting that when the novel was first published, and during the revolution Sara conjures in her imagination, inequality was as much a live wire as it is today. “This is not a revolutionary text,” she concludes, “but it is raising these questions and this feeling of discomfort.”

You might be thinking, What happened to simple “lived happily ever after”? Truth be told, that notion about kiddie lit is as imaginary as Sara’s Bastille: much children’s writing has plumbed adult themes of power and inequality, Henchman says. Her new course, which probes those themes, was developed in part through an Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program project last summer (UROP provides funding for faculty-mentored research by undergrad students). Having decided to create the class, Henchman enlisted UROP student Nina Becker Jobim (CAS’16) to research authors and assemble readings for the syllabus.

The School of Education runs a certificate program in children’s and young adult literature as continuing education for teachers. The CAS Writing Program also offers a children’s literature course this spring, but it discusses nonfiction (which Henchman avoids) and more contemporary works than those tackled in Henchman’s class.

“I’m looking at fairy tales, and then the golden age of children’s literature, which is 1860 to 1920,” and finally at some more recent authors, including J. R. Tolkien (The Hobbit, 1937) and C. S. Lewis (The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, 1950), she says. Her goal is “to reimmerse students in the stories that are familiar from childhood, and then encourage them to analyze the choices and the assumptions that are built into those stories.”

Cinderella, for example, assumes a world with a black-and-white option for its characters, Henchman says: “either abject penury and hard work or being the princess and having this glorious palace.” That either-or world is also the one depicted in A Little Princess.

The princess-or-peasant economy certainly existed in the feudal societies that are the settings for many fairy tales. But the golden-age Anglo-American literature that is the focus of Henchman’s course was produced by capitalist societies, marked by “rapid movements of wealth to poverty or poverty to wealth,” she says, so that rags-to-riches tales are an enduring kiddie-lit meme.

That these stories were meant as more than childish entertainment is a revelation to students. “I found it interesting that most of the children’s stories from years and years ago…were meant to give kids a sense of awareness, to warn them to behave, or else something bad could happen to them,” says Carly Kinscherf (COM’18). “They’re basically morals for kids.…I didn’t really think about the meanings behind them when I was younger.”

“I’d echo that statement,” says Dylan Berkey (COM’18). “It’s pretty funny to go back and read them and see what kind of themes pop up again and again.”

For Henchman, the professional is personal, and not just because she’s the mother of a six-year-old. She developed the class in part because as a child, she believed in Aslan, the titular feline in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, who represents Jesus Christ. “I was brought up by atheists, who told me they didn’t believe in God, and so I started to find my structures of meaning and my belief systems and my sense of right and wrong in children’s books. I literally believed that I would be kind of saved or at least watched over by Aslan.…I feel like my incredible attachment to the books that I read as a kid is exactly why I’m a professor now.”

This Series

Also in

One Class, One Day

-

November 30, 2018

Breaking Bad Director Gives CAS Class the Inside Dope

-

October 31, 2018

Trump and the Press: We’ve Been Here Before

-

August 3, 2018

A Scholarly Take on Superheroes

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.