Seeing beneath the Sugarcane

Technology and biology conspire to make buried settlements visible

For the past 1,500 years, crops have been grown with great success in the Chicama Valley on the north coast Peru, one of the driest places on Earth. The Moche people, who occupied the area from AD 100 to 800, cultivated chili peppers and potatoes, supplementing the area’s 0.2 inches of annual rainfall with water from an irrigation system that modern archaeologists only partially understand.

Today, irrigation in the Chicama Valley is typical of 21st-century agriculture. Only now, sugarcane blankets the region, much to the consternation of archaeologists, who know that ancient structures of the Moche people lie hidden beneath the ground. The densely grown 10-foot-tall stalks of cane are impossible to walk through without serious machete-wielding.

Boston University archaeologists have found a solution—remote sensing, which uses satellite cameras to record information about buried sites. Remote sensing is so effective that it can save archaeologists years of footwork by showing them where to dig, says William Saturno, a College of Arts & Sciences assistant professor of archaeology and a principal investigator of a Chicama Valley project funded by a NASA ROSES (Research Opportunities in Space and Earth Sciences) Space Archaeology grant.

In the video above, William Saturno and Benjamin Vining explain how remote sensing reveals long-buried structures in northern Peru.

“By using remote sensing, we essentially make the invisible visible,” says Saturno, who is collaborating with BU postdoctoral fellow Benjamin Vining (GRS’11) and archaeologists from Harvard and the University of Alabama. “We have the ability to see things that we would never be able to see by flying over a field or cutting down a field. We can get a sense of what no one else can see, and then use that to guide further research.”

For decades, the Chicama Valley has lured archaeologists with its massive 160-foot-tall mud-brick pyramids, called huacas. Huacas were sacred sites to the Moche, and their noble dead were often buried in them, alongside pottery, ceramics, and elaborate metalwork. Surrounding the huacas, and hidden beneath the thick sugarcane, are the ancient settlements where the common people lived. Those villages are what Saturno and Vining hope to study, because there, they say, is where the real stories of the lives of the Moche can be found.

Vining uses the analogy of future archaeologists trying to define life in New England by excavating the State House, Beacon Hill, and the Back Bay. “That would give you a very narrow and distorted view of what was happening,” he says. “We’re trying to identify and describe areas that would be analogous to Allston and Brighton to find more about the social lives of these people.”

Can be seen—just not by human eyes

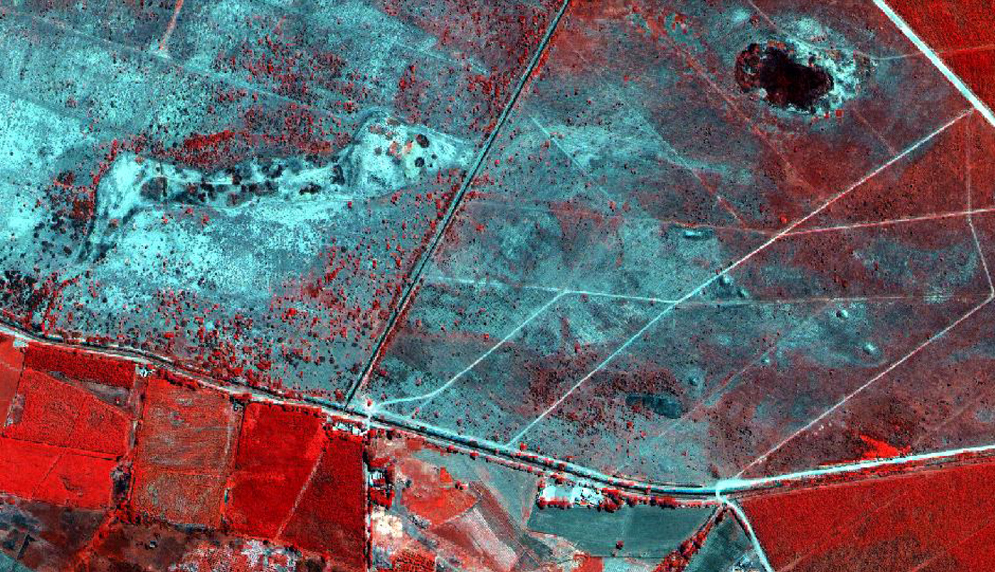

Fortunately for Saturno and Vining, the location of the buried settlements can be seen, just not by human eyes. Satellite-mounted remote sensors, which measure the wavelengths of light reflected from sugarcane, show a clear difference between cane growing above buried ruins and cane growing in settlement-free ground.

“We can see only a very narrow range of visible light that conforms to blue, red, and green wavelengths,” Vining says. “But satellites take a broader range of that spectrum, particularly in infrared wavelengths, and divide those up into multiple images. We can then manipulate those mathematically to look for relationships or patterns and focus on what is happening in the vegetation.”

In most cases, he says, vegetation is displayed in the red color. If it’s healthy vegetation, it will show up as bright red, if it’s sick or dying it will appear as dark red.

“Our research is showing that these archaeological sites accelerate the growth of plants,” Vining says. “The sugarcane is growing earlier and faster, but also dying off faster. It’s a more complex dynamic, and it’s out of phase with all of the plants around them. What is happening is different amounts of chlorophyll or different amounts of water are changing how the plants reflect light.”

When the team compares images taken during different times of the year and during different growing periods, they can spot small changes in the sugarcane leaves, and those changes can lead them to long-buried structures. Vining says the subtle shifts, seen in the reflection of light, indicate biochemical changes in the plants.

Vining says that in most cases, vegetation is displayed in the red color. If it’s healthy vegetation, it will show up as bright red. Sick or dying vegetation will appear as dark red.

Saturno says minute differences in sugarcane leaves have revealed settlements, unexplored huacas, and ancient irrigation canals. So far, he says, they have identified 550 growth anomalies in the fields of sugarcane using remote sensing. Approximately 120 of these are associated with previously identified huacas that can be seen rising above the sugarcane fields. The remaining 430 unexplored areas are ripe for future digs.

Saturno and Vining’s research may also help local farmers. If researchers can prove that the irrigation practices of the past covered broad areas using a low-cost gravity-fed irrigation system, the team could suggest improved agricultural practices, which could increase or improve the farmers’ production. And not just in Peru. The team believes that their findings about low-tech irrigation could also benefit farmers in other parts of South America, as well as in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

“This land is desertic, except for these valleys that are irrigated,” Saturno says. “The Moche had an important relationship with their environment in order to bring about the types of developments that they did. And we want to understand this relationship a little bit better.”

This Series

Also in

Dig

-

November 9, 2014

Secrets of the Three Cranes Tavern

-

November 9, 2014

Picturing a Long-Gone Citadel

-

November 9, 2014

Vikings: Menacing Marauders or Homebodies?

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.