One Class, One Day: The History of Rock and Roll

A good beat, and social commentary as well

Class by class, lecture by lecture, question asked by question answered, an education is built. This is one of a series of visits to one class, on one day, in search of those building blocks at BU.

Ohio radio DJ Alan Freed was the opening act for a revolution when he dubbed the pulsing, edgy music he was playing in the early 1950s “rock and roll.” He stunned one performer familiar with the term as a euphemism for sex. “I can’t believe you said that on the air,” he told Freed.

The anecdote is one of many that William McKeen drops like doo-wops in his summer term medley of music and social history, The History of Rock and Roll, covering R&R’s roots from its pioneering performers to 1970. This course sways to both the classic songs McKeen plays and the stories he tells to humanize the genre’s icons.

“I teach rock and roll history and defend my job with a straight face,” McKeen, a College of Communication professor of journalism and department chair, writes in his 2000 book, Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay. “The course exists for a good reason: more than any other form of popular music, rock and roll has embraced social commentary. It has a real historic value.” Rockers’ first cause was the one that plagued the country from its founding: race relations. By reinterpreting the R&B work of African American musicians in his first single in 1954, Elvis Presley integrated music at a time when much of America, including radio, was in Jim Crow’s grip, McKeen’s book argues.

Elvis, of course, is among the pivotal figures covered in the course. Yet he was an “interpretive” artist of others’ music, McKeen told students during a class focused on the man he calls rock and roll’s first great creative artist—Chuck Berry. Berry, he noted, wrote his own songs, made his on-stage “duck walk” famous, and became more than just a performer in the process. McKeen stressed the lyricism of “rock and roll’s first poet” and “the economy of his language. He can tell you an awful lot with a little.” Nadine, for example, describes a beautiful woman walking like a wayward summer breeze toward a coffee-colored Cadillac. “You can kind of see her as she sashays away,” McKeen said.

Berry’s lyrics fried bigger fish than merely describing cars and women. Brown-Eyed Handsome Man was actually code for “brown-skinned,” the song becoming an early anthem of pride for people of color, McKeen told his students. Too Much Monkey Business is “kind of a serious song” about a disaffected Army vet reduced to pumping gas after serving in a war. Perhaps most poignant is Memphis, about a six-year-old whose parents’ breakup leaves her waving good-bye to her father with hurry home drops on her cheeks.

McKeen described the genesis of Berry’s duck walk (he invented it while working as a barber to make people laugh) and of his first hit (he took a blues tune titled Ida Red to a record company exec, who found it too slow and told him to “goose it.” Berry came back with Maybellene.) He noted that for all Berry’s pioneering music, his only number-one hit was a 1972 novelty song about his sex organ, My Ding-a-Ling. According to McKeen, Berry never intended the song for release. “He was furious, until he started getting the royalty checks. Then he got over it.”

The main lesson McKeen wants students to learn is “the role that rock ’n’ roll played in introducing black America to white America. Because radio didn’t obey Jim Crow laws, it took music into places it normally wouldn’t be heard.”

These morsels are a highlight of the class for Nate Fisher (CFA’13). McKeen “knows so much about every story that influenced every event,” he said. Fisher wanted a summer class that could fulfill his liberal arts requirement, and “this is perfect. Music is my favorite thing in life.” He has long idolized Berry, thumped out Bo Diddley’s trademark beat on the table when McKeen asked if anyone knew it, and also accepted the professor’s invitation to do a pitch-perfect impression of Little Richard’s stratospherically high Wooooooo!

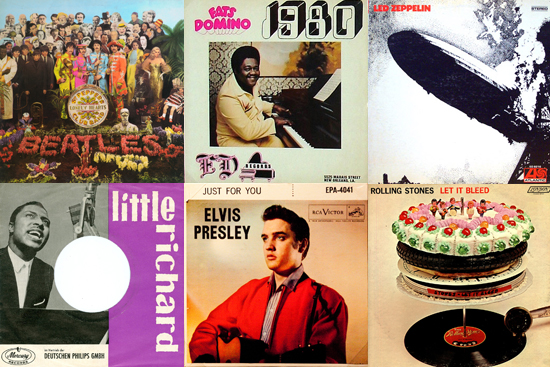

This enthusiasm, Fisher admitted, probably makes him unusual for his generation, to whom the 1950s might as well be the Middle Ages. (One quarter of the class hails from Metropolitan College’s Evergreen program for learners 58 and older.) “There are probably not a lot of kids my age listening to old rock and roll,” Fisher said. “But kids interested in music? Definitely.” And even nonfans appreciate the music and music-makers the class studies in rock’s later period, he said. “The Beatles, the Stones, Led Zeppelin—they’re never going to not be listened to.”

Anyway, old rockers never die; they just release children’s albums later in life, as Little Richard did with his 1992 CD Shake It All About, familiar to some in Fisher’s generation. As the man said, rock and roll is here to stay.

This Series

Also in

One Class, One Day

-

November 30, 2018

Breaking Bad Director Gives CAS Class the Inside Dope

-

October 31, 2018

Trump and the Press: We’ve Been Here Before

-

August 3, 2018

A Scholarly Take on Superheroes

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.