One Class, One Day: Beauty and the Body

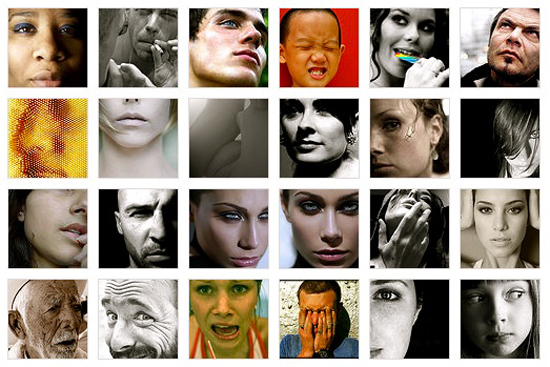

Is your idea of beauty racist and sexist?

Class by class, lecture by lecture, question asked by question answered, an education is built. This is one of a series of visits to one class, on one day, in search of those building blocks at BU.

If you think beauty is the subject of eternal, universal agreement, Jared Champion has a suggestion for you: take a look at Michelangelo’s famous statue David. Back in the early 16th century, says Champion, noting the statue’s modest genitalia, “large penises were considered grotesque.”

These days, when an entire cable TV series is built around a character who is well-endowed, it’s obvious that that standard of attractiveness has changed.

Hence the message of Champion’s College writing seminar, Beauty and the Body: notions of beauty are “not static, which means they’re not inherent, which means we have a lot more control over them than we think,” he says. The course is an offering of the College of Arts & Sciences writing program, required of most undergraduates at BU, regardless of school.

In a recent class, graduate writing fellow Champion (GRS’13) draws two stick figures on the board—one male, the other female. You might think such drawings would lose their pedagogical punch around the time students stop unfurling rugs for noontime naps, but Champion uses them to illustrate his students’ latent prejudices about a simple question: what is beauty?

Champion divides his class into two groups, assigning each a stick person and asking them to describe the appearance, from body shape to dress, that would qualify each as beautiful. Afterwards, both groups write their agreed-upon descriptions on the board. The ideal woman, according to the students, sports daisy dukes (super-short shorts popularized by a 1970s TV femme fatale), looks “all-American,” and has “relatively large” breasts, naturally blond hair, and fair skin. The supposedly gorgeous guy, meanwhile, wears boat shoes, a blue dress shirt, khakis with a belt, briefs, and a Movado watch.

Champion quickly spots some instructive points. Unlike the description of female beauty, the students’ vision of male beauty includes no body features.

What type of muscles should an attractive man have?

“Not obvious,” replies a female student.

“I’m supposed to go bust my ass,” Champion says, “to get some not-noticeable muscles?”

“Toned and sculpted,” the woman clarifies.

Champion pressed on: what about body hair?

“He doesn’t have any,” Sara Bustos (CAS’16) says.

“He looks like a nine-year-old?” says Champion to laughter, while more seriously noting the squarely upper middle–class background of a man who has such an expensive watch.

That “all-American” woman, meanwhile, is assumed to make slightly less than the man and is obviously white. Yet the group has given the male “more flexibility to not be white,” the teacher notes.

The bottom line, says Champion, is that “our notions of beauty are racist, they’re sexist, and xenophobic.” Perhaps, he concludes, we were raised with notions of beauty that are “untrue or incomplete.”

This is more than an aesthetic concern, Champion says. “There are power dynamics set up that are tied to these issues of beauty.” He notes that voters who watched the 1960 presidential debates thought the handsome senator, John F. Kennedy, whipped the wan, sweaty vice president, Richard M. Nixon, even though those who heard the debates on the radio gave Nixon the edge. Class readings include Ways of Seeing, British artist and critic John Berger’s book about unspoken underpinnings, such as male fantasies or social status, of Western art, and The Male Body, a feminist scholar’s take on social influences on our ideas about the body.

Nick Reisert (SAR’16) confesses that he signed up for Champion’s class because he figured that a course about beauty and the body had a high probability of being “full of girls.” And while that assumption turned out to be true, Reisert says, Champion’s discussions have become his favorite for reasons unrelated to the male-female ratio. With fewer than 20 students and lots of interesting conversations, “It is a great relief to take a break from large chemistry and biology lectures and talk about how we see each other through the looking glass.”

And yes, Champion has convinced him that “our views of normative beauty are skewed by things such as race, sex, and social class.”

Champion has also persuaded his audience that ideas about beauty change, sometimes more quickly than we imagine. He says that when he first taught this class several years ago, students offered the likes of Brad Pitt and Jennifer Aniston as examples of beautiful people. More recently, he says, celebrities like Jennifer Lopez, whose look is more exotic than Aniston’s girl-next-door image, and actor Jason Statham, who’s more muscular than the lean Pitt, have cropped up.

Everything changes, even our ideals, Champion says, and maybe they should, because the big question he wants students to wrestle with is this: what is it you think you know, and what are the assumptions that undergird it?

This Series

Also in

One Class, One Day

-

November 30, 2018

Breaking Bad Director Gives CAS Class the Inside Dope

-

October 31, 2018

Trump and the Press: We’ve Been Here Before

-

August 3, 2018

A Scholarly Take on Superheroes

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.