Writing a new prescription for Lesotho

BU professors try to put the "system" in the African nation's health-care system

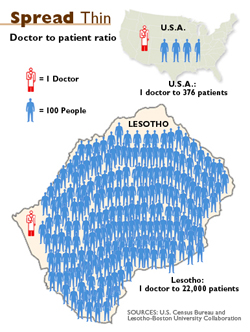

There are only about 90 doctors for the two million people living in Lesotho, a small, landlocked country in southern Africa, where the World Health Organization estimates that nearly one of every four adults, and more than 30 percent of pregnant women, are HIV-positive.

And Lesotho’s medical problem is not just about numbers. William Bicknell, a School of Public Health professor of international health, a School of Medicine professor of family medicine, and the director the Lesotho–Boston University Collaboration, says it’s also about inefficiency and lack of training. Administrators in the handful of district hospitals wait for months, or even years, for the central government’s OK for such things as repairing holes in the ceiling or replacing a much-needed doctor or nurse. Aid organizations donate expensive medical equipment, but there are no funds allocated to maintain the equipment, and foreign anesthesiologists are sent to hospitals that lack surgeons. Meanwhile, the country has no medical school and has trouble luring back native-born doctors trained in other countries, such as South Africa, because Lesotho lacks opportunities for more specialized medical training.

Earlier this year, the Collaboration, founded by Bicknell in 2003, was awarded a $195,000 grant from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. The money, says the BU professor, will help implement a five-year plan to strengthen Lesotho’s health-care system.

“The hospitals and clinics need help in terms of managing their scarce resources,” says Bicknell. “In addition to HIV/AIDS, all the other diseases are still there. They need to give physicians the skills to handle really sick people in a hospital and skills in front-line medicine and trauma care. And because physicians in district hospitals are also usually in charge of them, they need training in things like contracts and budgets.”

.jpg)

Bicknell is heading to Lesotho in June to meet with government ministers and health-care workers to draft a five-year plan to streamline how hospitals are managed and to lay the foundation for clinical training programs. Several BU colleagues will accompany him, including Mark Allan, faculty director of health sector management at the School of Management.

“It’s very challenging to run a health-care system when you have so little in terms of resources,” says Allan. “There are a lot of outside NGOs that have presences there, but our goal is to make the system work from the inside.”

On the managerial side of things, Allan says, the central government should give the district hospitals more autonomy in terms of their budgets, purchases of equipment and medicines, and decisions on hiring new doctors and nurses. “Right now, everything is too centralized. They can’t do anything without permission from the central government,” he explains, which creates “constant frustration” for hospital staff.

Plus, more autonomous and efficient hospitals will help the grant’s other main objective: getting more doctors and nurses to work in Lesotho, says Larry Culpepper, a MED professor and chairman of medicine and chairman of the department of family medicine at Boston Medical Center, who participates in the Collaboration and is the grant’s official recipient.

Consequently, Bicknell and his colleagues plan to establish a family medicine residency program in Lesotho and to develop curricula for additional training in obstetrics, surgical skills, and trauma skills, among other disciplines.

“The country is small enough that there’s tremendous potential to have a positive impact on the health-care system,” says Allan. “It doesn’t need to be elaborate. It doesn’t need to be fancy. But it has to be tied to people’s concrete needs and not abstractions."