Q&A with Prof. John “Mac” Marston

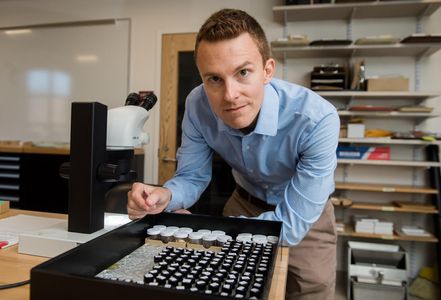

John “Mac” Marston is the Director of the Archaeology Program and the Environmental Archaeology Lab as well as an Associate Professor of Anthropology and Archaeology. His primary research is on environmental, economic, and agricultural archaeology as explored through land use and agricultural strategies of ancient civilizations. Within his lab, Professor Marston oversees research on sites in the Eastern Mediterranean and Central/Eastern Asia.

Q: Welcome Professor Marston! To start can you tell us a bit about yourself? How did you come to teach here at BU?

A: Well, I’ve been teaching at BU for 11 years now and to be honest, had very little thought of ever coming to Boston until I got this job offer. I did my Ph.D. at UCLA and after that, I taught at Brown for two years before I got the position at BU. At this point, I’ve now been teaching for well over 20 years, including in those other positions before I came here.

Q: What made you choose to teach?

A: I have always liked teaching. One of the aspects I really enjoy is the idea of being able to share the way that I do things as well as what I know. You get to share that with not just students but anyone who’s interested in archaeology, so I’ve taught in formal settings like the classroom but also in external contexts, like training students who might come to do an internship in my lab or in the field during the summer. Some of those students may be students I’ve had at BU, but I also get dozens of students from other universities and I get the opportunity to teach them about environmental archaeology. Opportunities like that have always been part of my training and I myself have learned a lot from great teachers so I feel like this is a wonderful career, especially since I get to do that same thing.

Q: That’s great, and you are no stranger to student opportunities. Last year alone, you were published in five different articles, and of those many collaborators were undergraduate, graduate, and alumni students. With all that experience publishing with students, do you have any advice for students who want to maybe publish or work with a professor but don’t really know where to start?

A: Of course! The typical way that students begin working with me in a research capacity is they might email me or take a class that interests them in the kind of research we’re doing in my lab. Then they ask, “Are there any opportunities to work in your lab?” and I say, “Yeah, we’d love to have you as a volunteer!”. After that initial outreach, we work on finding time in their schedule to come into the lab for a few hours a week to work on one of our ongoing research projects. Students often come in through that pathway, get some experience in the lab, and find out very quickly whether they enjoy it or not. And equally important they find out whether the flow of working in a lab is something that suits them. At that point, very often, we have opportunities for undergraduate students to do some kind of a directed research project through UROP, for example, or occasionally through fieldwork-based projects in the summer. Students engage in one of those activities, we work more closely together, and then the experience often culminates in a thesis project. This can be in the form of an honors thesis or we have some students who are in the five-year BA/MA program in Archaeology who end up staying for a master’s degree and doing a master’s thesis as well. After that point of close collaboration, it becomes possible to take the output of that project and turn it into something that can become publishable research. That’s the typical sort of progression for building those research skills and coming up with a project that eventually becomes something that we think is a real, viable contribution to knowledge and can potentially lead to publication.

Q: Speaking of your lab, the Environmental Archaeology Lab has now been at BU since 2013. Looking back at the last 10 years what kind of projects have you seen and what are some current projects?

A: In our lab, we do a variety of different types of environmental archaeology, which is applying archaeological methods to understand past relationships between people and environments. With that context, we are really designed to be a sort of multi-method laboratory and we offer equipment and supplies that can be used to do a wide variety of different types of analyses. That being said, I have a core area of expertise that stems from my own laboratory training and background in the analysis of plant remains and so the lab is fundamentally built around that. We provide really robust sample collections and reference collections that are useful for identifying seeds, pieces of wood, and other macroscopic things you can see with the naked eye. We have also developed new capacities over the years to look at microscopic types of plant remains- things like pollen- that we can recover from archaeological contexts. In those cases, we have kind of extended beyond my own core areas of analytical knowledge, so students who’ve worked in those disciplines have also gotten opportunities for advanced training elsewhere. For example, I have a former doctoral student who wanted to work on phytoliths, which are this type of microscopic plant remain. We sent her off to Barcelona for a semester to train with one of the leading experts in the world and afterward she came back and worked in the lab for her dissertation project. That’s a great example of how students often get involved in these projects based on some interest that they have that intersects with my areas of expertise. In some cases though, students just want a hands-on laboratory experience and this is one of the labs that we have on campus. They ended up trying it out and realize they really enjoy it or it engages some interest they have about topics in the past or the methods that they like, and so they stick with it.

Q: Focusing on your own research, your sites are quite a ways away, stretching from the Eastern Mediterranean to parts of Central and Eastern Asia. Can you tell us a little bit about these principal sites and what it’s like to work outside of the US? How much time is spent on-site vs back in Boston in the lab?

A: Yeah, so most of the projects I work with take place during our summer months because that’s when folks have the flexibility to go and travel. We typically work between May and July, we try to avoid August because it’s just too hot in a lot of places where I do research. My work has traditionally concentrated in Turkey and for the last decade or so in Israel as well. I’ve also taken part in other projects that are further afield, including a rather memorable field season about five years ago in Uzbekistan. We were actually hoping to establish a continuous project there but unfortunately, our key collaborator passed away at the beginning of the COVID pandemic. Hopefully, I will get back there soon, the experience was just remarkable. Working in these different countries, they’re very different from one another and have very different experiences. There are areas of Turkey where I feel, to be honest, more comfortable than other countries I’ve visited like England, which is a surprisingly foreign place to me. Turkey, you know, feels like home- and obviously having some ability to speak Turkish helps to facilitate that. It’s just a very comfortable place because I’ve been doing fieldwork in Turkey since 2002- that was my first field season there, so that’s quite a while ago now! The experience of going abroad on these excavation projects can really vary depending on the country and the location of the site. In one case, in a project I used to work on in Israel, we would stay in a hotel because we were right adjacent to a fairly large modern city in Israel. We would excavate the ancient part of the city and then go back to the hotel where there was a swimming pool and a bar and so on and there were about 100 to 150 people on this project at a time. Then you compare that to when I went to Uzbekistan, it took four flights to get where we were going as well as multi-hour drives and then I’m there in a small rented house with three other Americans, four Uzbek collaborators, and our cook- and that’s it. It was just us in this house, in this tiny village in western Uzbekistan. So the experience of being in the field can vary widely, which is one reason why I love it. Every time I’m involved in a different project, it’s a new experience.

A: Yeah, so most of the projects I work with take place during our summer months because that’s when folks have the flexibility to go and travel. We typically work between May and July, we try to avoid August because it’s just too hot in a lot of places where I do research. My work has traditionally concentrated in Turkey and for the last decade or so in Israel as well. I’ve also taken part in other projects that are further afield, including a rather memorable field season about five years ago in Uzbekistan. We were actually hoping to establish a continuous project there but unfortunately, our key collaborator passed away at the beginning of the COVID pandemic. Hopefully, I will get back there soon, the experience was just remarkable. Working in these different countries, they’re very different from one another and have very different experiences. There are areas of Turkey where I feel, to be honest, more comfortable than other countries I’ve visited like England, which is a surprisingly foreign place to me. Turkey, you know, feels like home- and obviously having some ability to speak Turkish helps to facilitate that. It’s just a very comfortable place because I’ve been doing fieldwork in Turkey since 2002- that was my first field season there, so that’s quite a while ago now! The experience of going abroad on these excavation projects can really vary depending on the country and the location of the site. In one case, in a project I used to work on in Israel, we would stay in a hotel because we were right adjacent to a fairly large modern city in Israel. We would excavate the ancient part of the city and then go back to the hotel where there was a swimming pool and a bar and so on and there were about 100 to 150 people on this project at a time. Then you compare that to when I went to Uzbekistan, it took four flights to get where we were going as well as multi-hour drives and then I’m there in a small rented house with three other Americans, four Uzbek collaborators, and our cook- and that’s it. It was just us in this house, in this tiny village in western Uzbekistan. So the experience of being in the field can vary widely, which is one reason why I love it. Every time I’m involved in a different project, it’s a new experience.

So the experience of being in the field can vary widely, which is one reason why I love it. Every time I’m involved in a different project, it’s a new experience.

Q: Sometimes we tend to see cultural anthropology and archaeology as two separate disciplines. As a professor in both the archaeology and anthropology departments do you see this divide reflected in classes or research and if so how do situate the two disciplines together?

A: Well, most archaeologists in the United States are trained as anthropologists so we have strong backgrounds in biological and cultural anthropology as well as in archaeological methods. A lot of the theoretical frameworks that we work with come from anthropology writ more broadly. That is certainly a very comfortable theoretical space in which I find myself, but I also work at the very science end of the spectrum in archaeology. We have folks here who are more at the historical end or more on the social theory end of things and I find myself really on the science end. As such, I really find myself working with primary materials that are actually more scientific methods and literature often written by geologists, botanists, and other folks like that. Because of that, I’ve always been somebody who’s been between and among different disciplines. Here at BU, I’m also on the faculty of the program in Biogeoscience, which is primarily comprised of faculty from Earth and Environment, Biology, Chemistry, and a few other departments. That’s another place where that sort of inter-disciplinary, intersectional area between the sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities, is a place where I’m quite often finding myself.

As such, I really find myself working with primary materials that are actually more scientific methods and literature often written by geologists, botanists, and other folks like that. Because of that, I’ve always been somebody who’s been between and among different disciplines.

Q: It shows that intersectionality is a major factor in your research and teaching. With buzzwords from different disciplines like ‘environmental archaeology and ‘agricultural economy’ popping up in your research how do you define your central research topic and how do you connect the dots so to speak?

A: My core interest is in using the study of agricultural systems in the past to understand connections between people and environments, and the connections that we can see through agriculture are particularly meaningful for understanding that relationship because people use agriculture as a way to dramatically transform landscapes. People adapt their agricultural strategies to climatic conditions, to the nature of the soils, the plants, or some other aspects of the natural environment. Through this, we observe how humans both respond to environmental change and actively- whether intentionally or not- create environmental change and I see agriculture really at the core of that relationship, which is why it’s always been my focus. I choose to focus on agricultural systems in the areas that I do, in Eastern Mediterranean, Western Asia, and Central Asia, primarily because these areas are rather dry, and yet they’re home to early agricultural societies. As a result, it’s a great place to understand the intersections between the cultural dynamics that are shaping societies over the span of 1000s of years, environmental changes, and agricultural systems that have to function really at the edge of where agriculture is feasible. In some of these places, droughts and bad crop years are huge problems because if you fall a little bit lower than the threshold for rainfall for your crop, you can have fairly massive failures. People need to be very strategic about the way that they do agriculture as a result, as opposed to a place that may have much better or more consistent environmental conditions and agriculture might be less of a risky proposition. There’s a little bit less adaptability in that system, it doesn’t need to change very much to suit the various conditions. I like to instead see how agriculture operates on the edges and how societies respond to that type of dynamic situation.

Q: Environment has been a big topic of discussion in recent years, do you feel like your research on ancient environments feedback into current climate research?

Q: Environment has been a big topic of discussion in recent years, do you feel like your research on ancient environments feedback into current climate research?

A: Yes, absolutely. One of the reasons why scholars in my discipline study these systems in the past is to gain a better understanding of both the relative dynamics between processes of cultural change and historically contingent phenomena, and how that relates to agricultural practices over millennia. By using the past lens of archaeology we can see the stimulus and the associated response and we can also see what the outcome of that strategy was. In the present day, we can often look at a stimulus and we can see a response or debate responses, but we have no way to see the outcome of it until we wait for the future. So archaeology provides this amazing lens that allows us to use, in a comparative fashion, the knowledge of how people have responded in the past to similar types of stimuli and whether those were successful or unsuccessful for current adaptations to change.

Q: And those dynamics are definitely catching the attention of the public. In fact last semester, you were featured in BU Brink’s Top 10 Discoveries of 2022. Congratulations! Can you tell us a bit about that project?

A: Thank you, that paper was quite interesting for me from a variety of angles. It was, I believe, my only publication in Maya archaeology and the reason behind my involvement was that some collaborators came to me with a botanical question and we solved it together and through that solution found that it gave us a new understanding of an archaeological context. The context was that they’d excavated these pits in the middle of a Maya city, and had found within them instead of the typical types of microscopic botanical remains that we often see such as starch grains or phytoliths -these incredibly durable silica structures that form within plant cells- they found something that kind of looked like starch but wasn’t starch. Through analysis, we were able to figure out that it was a structure called a spherulite. These are formed when starches essentially untangle and reform into something that I can only describe as a three-dimensional koosh ball, it’s this big furry mass. This spontaneous reorganization only occurs under very specific conditions, but in the immediate prior year I’d worked with an undergraduate student here at BU, actually part of her senior thesis, identifying how corn or maize is transformed by the process of nixtamalization. This process occurs when we chemically convert the corn grains into hominy, as we often call it in North America, that we then use to make masa flour for tamales and tortillas. During this process of converting corn to hominy, these spherulite structures form in the starch particles. We found those in this Maya context and a more careful archaeological investigation revealed that what we probably had here was a cistern built into the house. There were two of them next to each other in these small rooms and they seem to contain, well, primarily three things. They contained a bunch of burned ash, they contained lots and lots of these starch spherulites from the nixtamalization process, and they also contained a few eggs from fecal parasites. These eggs were from human intestinal parasites that are spread through that waste mechanism, so we knew we had human feces in these pits. And by putting these pieces of evidence together, we were able to reconstruct that these actually served as latrines. Whether they were always latrines, we don’t know but at some point in their use, they became latrines. People were likely taking the water that they used to create this nixtamal, which had lots of these starch spherulites floating around in it, and they were using it to essentially flush their toilets. Now the advantage to this is that it is a highly alkaline solution because they often used lime, chemical lime, as a chemical to catalyze this process. And that chemical lime is exactly what people dump in pit toilets today to minimize the smell. So by putting lime in there, it kills microbial activity and raises the pH substantially, and here was a liquid that was a waste product anyway, and also happened to be high in lime. They could use that as their flushing liquid and that’s what we think we have in these in these structures which is what the article was about.

Q: Quite interesting, and you can read the full article with BU Brink here. Well thank you for your time today, before we go is there any news, publications, or classes that you would like Anthropology students and faculty to keep an eye out for?

A: I would say probably one of the more exciting things that we have coming up is we are offering a summer class that has recently been converted for the summer session. As part of the spread of BU Hub credits, we have been trying to offer more Hub-related courses in the summer. This newly converted course, which I have taught as well as a colleague, is called AR280, Eating and Drinking in the Ancient World, and carries several Hub credits. The course focuses on the archaeology of food and has also been adapted into an asynchronous online format for the summer. It’s a great opportunity for students who would like to take a summer class but can’t be at BU or maybe have a nine-to-five job during the summer. We offered for the first time last summer and the response was great, the class filled up pretty much instantly! We’re going to offer it again next summer at an even larger capacity so hopefully, people will be able to take advantage of it.