Welcome to America?

Examining the history of anti-immigrant sentiment

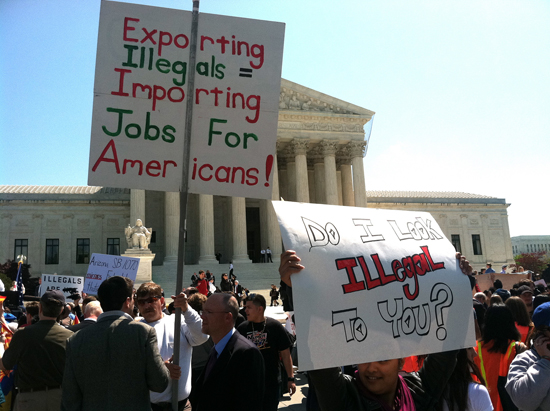

Protesters for and against Arizona’s recently invalidated immigration law demonstrate the country’s conflicted view of newcomers. Photo courtesy of Talk Radio News Service

Class by class, lecture by lecture, question asked by question answered, an education is built. This is one of a series of visits to one class, on one day, in search of those building blocks at BU.

Waves of immigrants have heeded the poet’s call to give America “your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” Yet there’s a backlash of fear that foreigners will snatch precious jobs from native-born workers—a reaction all the more virulent because many newcomers are minorities. Rachel Schneider sums up the objection for the 20 students in her class: “This is a perfect worker, if you’re a boss. But if you’re competing with them…”

Such is politics—in the Gilded Age. For all today’s Sturm und Drang over immigration, Schneider (GRS’14) actually is describing the run-up to the first federal anti-immigrant laws, which targeted Chinese workers in the 1870s and ’80s. That fear for lost jobs “might be a bit more familiar to us now in our current climate,” Schneider says, underscoring the relevance of history and this particular history course, Anti-Immigrant Sentiment in the United States.

A graduate writing fellow at the College of Arts & Sciences, Schneider directs students’ gaze through both the rearview mirror of the past and the window of the present to observe the country’s conflicted heritage of welcome for, and aversion to, new Americans.

The lesson learned by class member Claire Peaceman (CAS’16) is that this debate “is nothing new. We’ve been arguing the same things for almost two centuries.” That’s an important perspective at a university with a significant international student presence, and in an election year in which illegal immigration has become a flashpoint. More than 800,000 people—immigrants brought to the country illegally when they were children and meeting certain conditions—are eligible for a two-year moratorium on deportation under a policy President Obama approved in June. Republican rival Mitt Romney has pledged to honor the moratorium if elected; meanwhile, the GOP platform would require employers to confirm that workers are in the country legally, would ban federal support to state universities granting in-state tuition to illegal immigrants, and calls for “humane procedures” encouraging voluntary repatriation.

Opening with the surge of Irish Catholic immigration in the mid-19th century, Schneider moves on to the subsequent hostility against the Chinese who came because of the California Gold Rush and to build the transcontinental railroad; the post–World War I immigration quotas sparked by fear of European refugees; and the 1965 lifting of restrictions on immigrants, Asians particularly, which continues to redraw the face of the country. The course also ponders such contemporary conflagrations as Arizona’s tough immigration law. (The Supreme Court invalidated most of the law in summer 2012, but kept a provision allowing police to check the immigration status of anyone they detain.)

Arizonan Celia Simpson (CAS’16) took the class precisely because of her home-state debate. “I have learned just how far back the sentiment goes in American history,” she says, “and that it has been for reasons other than the economic toll that people claim immigration takes on our country, which is the main battle cry I hear in the current debate.”

Her own stance remains undecided—and that’s to Schneider’s credit, Simpson says. Her teacher “does a really good job of presenting the lessons in an unbiased way, and I think that we are expected to take the reading and information and form an opinion independently.”

Throughout, the class asks, how do you know you belong to a community, and who decides that? The advantage of history in considering those questions is that it insulates students from the electric shock of current controversy. Schneider hopes students simultaneously welcome immigrants and listen to the arguments of those wary of them for reasons of economic insecurity. The battle lines in this debate can be surprising, she says; she’s had native-born students with a multicultural outlook who say, “We can bring in whomever,” while a lot of first-generation Americans from immigrant families endorse limits on who can enter the country.

Anyway, times and attitudes change. We know from history how the anti-immigrant movie ended when it starred Irish newcomers in the 1800s. Looked down on, discriminated against, hired for only the most menial jobs (“Irish need not apply”), they fought their way up by sheer volume of numbers, especially in the Boston area. Schneider tells an anecdote she heard from a recent BU graduate studying Irish immigration, who interviewed an Irishman here illegally. “This man said he came over to the United States, and that you’re supposed to have enough money to prove that you can buy a return ticket,” says Schneider. “He only had $50. The immigration official just waved him through and said, ‘Welcome to Boston.’”

This Series

Also in

One Class, One Day

-

November 30, 2018

Breaking Bad Director Gives CAS Class the Inside Dope

-

October 31, 2018

Trump and the Press: We’ve Been Here Before

-

August 3, 2018

A Scholarly Take on Superheroes

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.