Emily Sanchez (middle row, far right), an Army captain stationed in San Antonio, Tex., was mobilized to run food service operations at a field hospital in New York City when COVID-19 spiked in the city. Photo courtesy of Emily Sanchez

CONTACT TRACING HAS BEEN LAUDED AS A KEY TOOL IN THE EFFORT TO STOP THE SPREAD OF THE NOVEL CORONAVIRUS, breaking the chains of transmission and preventing infection surges by identifying and helping those potentially exposed to the disease. It’s also one of the oldest public health tactics around: the Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC) Infectious Disease Bureau—founded in 1799 and initially led by Paul Revere—has used it to control the spread of diseases like cholera and tuberculosis. When the volume of cases from the COVID-19 pandemic overwhelmed the small nurse-staffed office, officials reached out to Boston’s higher ed community for help.

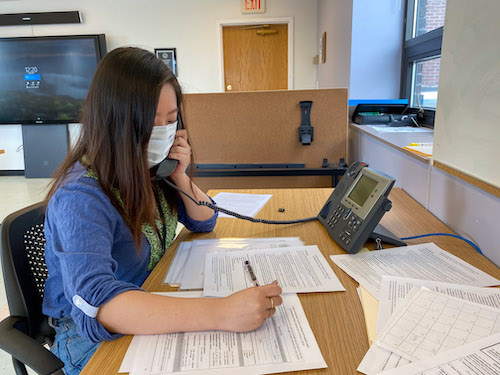

Shelley Brown, a clinical assistant professor of health sciences, emailed a group of her students, including those who’d lost internships because of the pandemic. Within two hours, more than 30 students had responded, and 10 ultimately volunteered.

The BU volunteers each made 25 to 30 calls a day during six-hour shifts at BPHC’s Dorchester offices. The city offered scripts to the contact tracers, but most participants say their real-life conversations took freewheeling twists and turns.

Natalia Kelley (CAS’22, Sargent’22) says she tried to let her calls unfold like conversations to build a sense of trust before asking people intimate questions about their symptoms and recent personal interactions. But it wasn’t always easy. One woman was angry that the city received information about her positive diagnosis. Others shared their symptoms in graphic detail. In fact, many were comfortable right away talking about their health symptoms, whether diarrhea, excess phlegm or mucus, or other less-than-pleasant topics, because they wanted to help the city’s efforts to curb the virus’ spread.

The contact tracing effort also helped record the demographics of Boston’s infected population, which contributed to broader information nationally. According to the COVID Racial Data Tracker, a collaboration between the COVID Tracking Project and the BU Center for Antiracist Research, Black Americans are dying from COVID-19 at a rate almost 2.5 times greater than white Americans. Latinx people are dying at a rate 1.3 times greater.

Some of McKenzie Beaton’s calls were to Spanish-speaking immigrants—many of whom were not getting needed healthcare services before the coronavirus or fact-based information during it. Beaton (’20, SPH’20), who is bilingual, says many of the people she spoke with were living in small or crowded apartments and struggled to avoid contaminating others. “This systemic inequality—I’ve been studying it for four years,” she says. “It’s a really hard pill to swallow.”

—Megan Woolhouse

WHEN THE PANDEMIC HIT BOSTON, UMA KHEMRAJ (’21) LEARNED THAT MANY OF THE city’s homeless shelters were struggling to obtain hand sanitizer. The shortage was so severe that, by late March, even 25 percent of healthcare facilities were almost out of hand sanitizer, according to an Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology survey. The founder of a student club focused on healthcare advocacy, Khemraj decided to take action.

She had started Healthcare Improvement, Inc., in January, after taking a health and human rights course at BU School of Public Health. The organization’s aim is to advocate for improved healthcare at all levels of government, with an emphasis on human rights—and the COVID-19 pandemic provided an immediate focus. “It’s unacceptable that there were so many people disproportionately affected by the virus because of their socioeconomic circumstances,” says Khemraj. So she put out a call to local businesses and schools for sanitizer donations.

By late April, the organization had collected around seven gallons of hand sanitizer from Short Path Distillery in Everett, Mass., and GrandTen Distilling in Boston, as well as students from BU and other universities.

Khemraj personally delivered the donations to Boston Rescue Mission, Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, and Haley House. “There were so many people lining the streets without masks and without gloves,” says Khemraj of her visit to the Boston Rescue Mission. “That really made an impact on me.” It inspired her to research additional ways to support those disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, focusing on other critical health resources. One of her next goals is to publish a journal about the intersection of economics, public health, and medicine. “It’s all about getting the word out,” she says. “We can really make a difference here if enough people know and if enough people care.”

—Jacob Gurvis

ambulatory COVID-19 testing site. Photo courtesy of Lauren Tamburello

ambulatory COVID-19 testing site. Photo courtesy of Lauren Tamburello[/caption]

IN MARCH, AS BOSTON’S CORONAVIRUS CASES BEGAN TICKING HIGHER AND HIGHER, THE CITY’S HOSPITALS were stretched thin. With elective and routine appointments put on hold, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) was one of those that asked for staff volunteers prepared to switch to frontline care. Lauren Tamburello was quick to raise her hand. “My boss was not surprised,” she says. “She knows I like to be in the action.”

A program manager at BIDMC’s Division of Urology, Tamburello (’15, SPH’17) typically works to improve processes and programs that enhance the patient experience. In mid-March, she was redeployed and assigned as a site manager at BIDMC’s ambulatory COVID-19 testing site. There, she handles the day-to-day operations of the hospital’s outdoor, drive-through location, where a team of nurses, medical assistants, and other allied health professionals—including occupational therapists, audiologists, and radiation technologists—perform the nasopharyngeal swab test.

In managing the testing site, Tamburello has had to quickly adapt to changes in hours, testing guidelines, staffing, and even the weather. As of mid-August, the site—which operates seven days a week and, on the busiest days, tests more than 100 patients—had administered more than 15,000 tests.

“Our team is doing a fantastic job of taking care of our patients,” Tamburello says. But, she adds, it’s been emotionally and physically exhausting. “I’ve seen staff who are having a difficult time working in this COVID testing environment when they’ve lost loved ones to the virus. I’ve seen staff members who are ‘swabbers’ or work in the test scheduling office who are concerned because they have little ones at home,” she says. “It’s been one of the hardest and most challenging things I’ve had to do in my career, but also the most rewarding.”

—Mara Sassoon

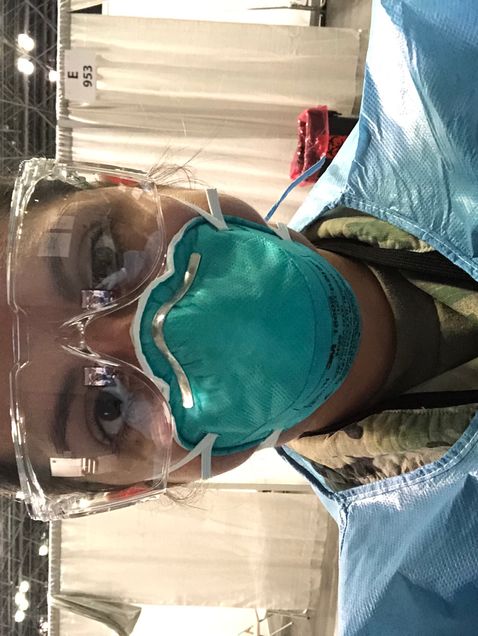

WHEN EMILY SANCHEZ (’13) GRADUATED, SHE APPLIED FOR THE US MILITARY–BAYLOR Graduate Program in Nutrition in San Antonio, Tex. Despite having no military background, “I really felt like being an army dietitian, I would never get bored,” says Sanchez, who is now a captain. “I would always be challenged and, every couple of years, have to tackle new problems.”

In late March, after seven years of clinical nutrition and dietetic work at army medical centers in Georgia and Texas—most recently as chief of community and outpatient nutrition at the Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio—Sanchez received an assignment that would test her nutrition expertise and military experience in new ways. At the height of COVID-19’s initial spike, she was mobilized to run food service operations at the Javits New York Medical Station, a field hospital built in a convention center in Manhattan, which opened March 31.

Sanchez’s primary focus was ensuring that the hospital received all the supplies and food it needed from outside partners—which included more than 40 collaborating agencies. Sanchez also oversaw a team of dietitians and nutrition care specialists, working to provide healthy meals and nutrition services to all patients.

The hospital served more than 1,000 patients by the time it concluded operations on May 1, with Sanchez and her team distributing more than 15,000 meals. Though her service in New York lasted just five weeks, the community’s support has stuck with Sanchez. She recalls New Yorkers applauding as she and her colleagues returned to their hotel after each 12-hour shift.

“It was a small act of kindness and gratitude,” says Sanchez, “but it meant so much to me and my team, knowing that what we were doing in New York had meaning and affected the people living there every day.”

—Jacob Gurvis

IT WAS BUSINESS AS USUAL AT THE BOSTON CONVENTION AND EXHIBITION CENTER IN JANUARY 2020: an auto show, an RV and camping expo, trade shows. By early April, its typical run of annual meetings and events had been canceled and the sprawling venue turned into a temporary, 1,000-bed field hospital, Boston Hope. Over the next two months, the hospital would treat hundreds of postacute COVID-19 patients. And it was Nicolette Maggiolo’s job to make sure they all got healthy meals.

From April until June, Maggiolo (’15), a registered dietitian, was the nutrition and food services manager at Boston Hope. She oversaw food service and nutrition counseling for more than 750 patients at the temporary facility, which was built and operated by her employer, HomeBase, a Red Sox Foundation and Massachusetts General Hospital program that provides clinical care and wellness education and support to veterans and their families.

Her role included managing Boston Hope’s clinical nutrition staff, helping patients plan for their transition home, and coordinating with the convention center’s catering company. Working with a nonmedically trained catering company in an untraditional hospital space provided its challenges. But obstacles aside, Maggiolo says the nutritional health of the hospital’s patients was critical to the healing process.

Nothing could fully prepare Maggiolo for such important work, but she was confident her Sargent training would help her rise to the occasion. “I always had such incredible mentors at BU,” Maggiolo says. “They always gave me the confidence that no matter where I landed or whatever role I was asked to take on—even if I wasn’t totally sure I had the résumé or the exact qualifications for it—that I could do it, and that I could do it well.”

Maggiolo called one of those old friends for advice. Emily Sanchez—see above—gave Maggiolo her first tour of Sargent, and Maggiolo credits her as the reason she chose BU.

“To call her and collaborate with her and pick her brain and bounce ideas off of her was so, so helpful for me,” Maggiolo says.

Looking back, Maggiolo recalls her final day on the job. The staff of Boston Hope formed a tunnel outside the convention center to cheer on the final patients as they were discharged.

“That will forever be a part of me,” she says. “I’ll always think back to that tunnel and those patients being wheeled out and making their way home after being treated at Boston Hope. That was a really beautiful day.”

—Jacob Gurvis