On Their BEST Behavior

Every summer, the Museum of Science, Boston, offers children’s programs on subjects like rockets, dinosaurs, and electricity. The programs are popular with children on the autism spectrum, who may have an aptitude for science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), and develop focused interests in these areas. These children also have difficulty with social interaction; at the start of a program, they would be more likely to pull out a book during lunchtime, rather than eat with the other kids, says Annette Sawyer, director of the museum’s education and enrichment programs. As the program progressed, however, Sawyer noticed that the children and their peers connected through their shared interest in science. Sawyer set out to see if there was more the staff could do to create a supportive learning environment for the children with autism. In 2009, she called Sargent for help.

Ellen Cohn, a clinical professor of occupational therapy at Sargent, and her colleagues began working with Sawyer and her staff to make the museum more inclusive. In 2011, this collaboration expanded into the Buddies Exploring Science Together (BEST) program, a partnership of Sargent, the museum, and Boston Public Schools (BPS) that serves children with autism. Each spring semester, the OT students from Cohn’s Group Leadership Experience course co-lead a group of 15 BPS students ages 9 to 16 on weekly field trips to the museum. Now in its fourth year, the BEST program “flips the conversation about youth with autism” says Cohn, who is also the director of Sargent’s Entry-Level Doctorate in Occupational Therapy (OTD) Program.

Typical interventions for people with autism focus on addressing an individual’s social deficits and on teaching social skills, such as making eye contact and conducting a reciprocal conversation. These lessons often take place in a classroom or clinic and are not easily transferable to other environments and situations, says Cohn. “We know it is helpful to teach in context, and the Museum of Science is a highly engaging, interactive, and motivating environment,” she says. “Because the content of the exhibits is so compelling to youth, they have a great desire to be at the museum, and because they have an interest in the exhibits,” they’re more likely to share that interest with others. They’re learning new things, and they are interacting socially—and spontaneously—with support from Sargent’s OT students.

For the first two weeks of Cohn’s class in January, the OT students get to know the children in the BPS classroom setting. Together, they develop social stories, booklets that outline the activities the children will participate in at the museum and identify the behavior expected of them. For example, “When we get to the museum we will walk together to meet Museum Teachers. Museum Teachers wear red coats and they will help us learn about science.” They also set learning and social participation goals for their visit, such as “I will ask my friends questions about themselves and their interests” and “I will share things with my partner.” This goal-setting process is vital, says Cohn, because the children “are more intentional when they set specific goals, and we see better outcomes when the goals are co-constructed or negotiated” between the OT students and the children.

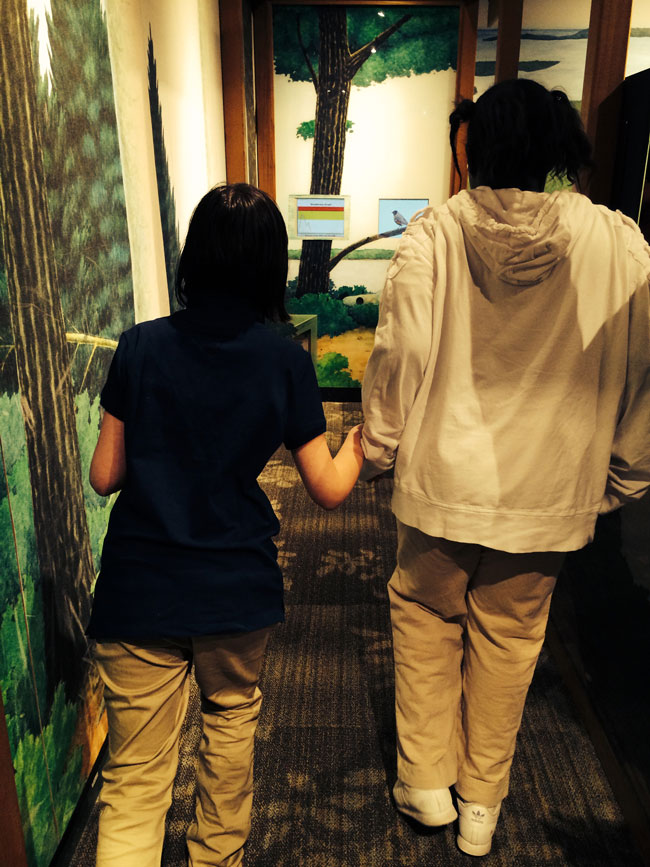

The children’s enthusiasm underscores the success of the program. They have expressed excitement with comments like “awesome” and “cool,” asked questions, and participated in presentations. During the time provided for independent exploration, they often lingered at exhibits that interested them. One child asked a friend to “come over here and look at the armadillo,” and another asked his teacher to join him in looking at a shell. “That’s the kind of spontaneous interaction that happens at the museum that we don’t think would happen in the classroom,” Cohn says.

At the end of each visit, the OT students reinforce the children’s goal-setting by pointing to specific examples of their successful behavior. It’s important for the youth to assess for themselves whether they met their goals because “we’re trying to promote their perceived sense of competence in their ability to be successful science learners and social participants,” Cohn says.

At the end of the program, the OT students and museum staff also interview the teachers about how the visits benefit their students, and how BEST reinforces their learning goals. According to teacher assessments before and after the 2014 program, 9 of the 15 children demonstrated improvement in skills such as participating in group activities, sharing with others, and demonstrating flexibility in unplanned situations. The children, too, reported improvement in their social skills and behaviors.

The OT students benefit as much as the youth. “It’s all about the community,” Cohn says. Through the BEST program, the OT students “learn that some of our partners don’t necessarily have to be medical practitioners in a hospital or rehabilitation hospital. Our partners can be educators and exhibit designers and docents in museums.”