Conversation with Gregory Williams about postwar art in Germany

By Arthur George Kamya (American & New England Studies)

July 2020. Professor Gregory Williams of BU’s History of Art & Architecture department was awarded a 2020 NEH Summer Stipend to work on his book project Practical Aesthetics: The Object of Postwar Art and Design in West Germany. NEH Summer Stipends support projects in the humanities where summer funding is limited compared to the social and natural sciences. What follows is Williams’s discussion of his current work with the Center’s graduate intern, Arthur George Kamya.

Does Practical Aesthetics grow out of your first book Permission to Laugh: Humor and Politics in Contemporary German Art? Why postwar Germany? Why Germany, laughter and humor?

Permission to Laugh grew out of my pre-graduate school experience working in museums in the US and spending three years studying and working in Germany. As I struggled to learn the language, I came to the realization that there is much about Germans and German culture that remains incomprehensible to Anglo-American scholars. For example, the false trope of the humorless Germans. On the contrary, close examination of German literature and visual art reveals a deep comedic tradition from corporeal humor in the middle ages to 18th and 19th century adherents of the grotesque. Permission to Laugh not only spotlighted the salience of irony, jokes and play in contemporary West German art of the 1970s and 1980s; it also revealed a specifically German variant of postmodernism, with a skepticism toward tradition, institutions, and linear history that links it with developments in the US and elsewhere in Europe. In the case of German culture, this turn to humor was marked by a critical reflection on taboos of speech and image-making in relation to Germany’s fraught past.

Permission to Laugh grew out of my pre-graduate school experience working in museums in the US and spending three years studying and working in Germany. As I struggled to learn the language, I came to the realization that there is much about Germans and German culture that remains incomprehensible to Anglo-American scholars. For example, the false trope of the humorless Germans. On the contrary, close examination of German literature and visual art reveals a deep comedic tradition from corporeal humor in the middle ages to 18th and 19th century adherents of the grotesque. Permission to Laugh not only spotlighted the salience of irony, jokes and play in contemporary West German art of the 1970s and 1980s; it also revealed a specifically German variant of postmodernism, with a skepticism toward tradition, institutions, and linear history that links it with developments in the US and elsewhere in Europe. In the case of German culture, this turn to humor was marked by a critical reflection on taboos of speech and image-making in relation to Germany’s fraught past.

Working on the 1970s piqued my interest in German art over the course of the previous couple of decades — the subject of Practical Aesthetics. But, to answer your question, this project has little to do with the emphasis on linguistic and visual play of the first book. The new project benefits from the fact that West German artists of the 1950s and 1960s have enjoyed something of a critical renaissance of late. The idea for the book grew out of a presentation I gave at a 2010 symposium on the work of one of these artists, Franz Erhard Walther. The symposium accompanied an extraordinary exhibition of one large work (or group of works) by Walther, known as his First Work Set (1963-69). Displayed at the Dia:Beacon art museum in New York, the First Work Set consists of over 50 objects with which viewers were meant to interact — by feeling, touching and even wearing them — as single individuals and as groups of people. In dialogue with 1960s themes of minimalism, participation, environment, and phenomenology, Walther both engages and transgresses those discourses. His oeuvre not only interpolates the textual and the representational, it also complicates the body’s relationship with art, especially sculpture. Having made this work in the 1960s and produced a great deal since then, Walther, who is still very active, has gained significant international visibility only in the past decade.

First Work Set, 1963-1969

Detail: Form for Body (No. 29), 1967

Franz Erhard Walther Foundation, Fulda, Germany

What role do these Werkkunstschulen — the innovative schools of art and design responsible in part for the vaunted post-war German economic miracle — play in Practical Aesthetics?

Unlike their predecessors who would have trained entirely at prestigious art schools, the artists I address, including Walther, initially attended these regional schools where they imbibed a vocational ethic. Having received training in less overtly art-based skills such as typography and hand-lettering at the Werkkunstschulen, they were able to produce work that disturbed traditional conventions of artistic expression. First, by effacing the signature brushstroke of the artist as singular creator, they removed the romantic artist from the pedestal, moving toward a more collaborative creative process. Second, by replacing individual-artist-centered media such as paint and canvas with industrial forms, they permitted materials to speak for themselves.

Loosening the boundaries between object and subject and conflating the viewer with the work, Walther roots himself firmly in cultural developments of the 1960s and 1970s. The tendency of these artists to deconstruct the ideal of the brooding genius artist was consistent with the larger project of Germans in the post-war period to come to terms with their history. Whereas many of these artists ultimately— later in life — reproduced some of the hierarchies they had initially challenged, the book seeks to identify a certain subversive esthetic imparted by their vocational training that nonetheless still marks their works.

Do you consider yourself an art historian or a German Studies scholar? Do you study the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) as well as what was known as West Germany before reunification?

Not being a scholar of classic German figures like Kleist or Goethe or Nietzsche, and given the fact that I write about international artists on a regular basis, I hesitate to call myself a full-fledged German Studies scholar. Nonetheless, I consider myself a member of the German Studies community. I am a semi-regular attendee of conferences sponsored by the German Studies Association. Perhaps because of their homes in history, literary theory, philosophy, and social science departments, some German Studies scholars have long accommodated and adapted themselves to critical reappraisals of the so-called canon by invoking theories of race, class, gender and post-coloniality. Like those other scholarly communities, German Studies has struggled to come to terms with its own complicity in imperialism, colonialism and racism. Perhaps historically more invested in the immutability of a canon than some fields, my own home discipline of art history has been slow in embracing similarly critical self-reflection. However, I am heartened by what I take to be art history’s more recent openness to self-appraisal. This tendency of art history to learn and grow, in the spirit of interdisciplinarity and crossdisciplinarity, is one I associate myself with wholeheartedly.

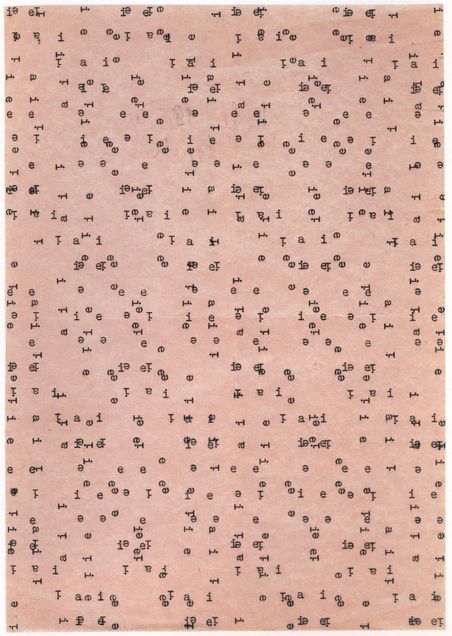

Letternfeld (Letter Field), 1959

Typescript on office paper, 21.0 x 15.0 cm

Carlfriedrich Claus-Archiv, Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, Germany

A major theme of my work has been contextualizing contemporary art in the frame of contemporary politics and society. In spite of long-running assumptions that there was no alternative, non-state-sponsored art in the GDR, artists in East Germany did find space for themselves, despite state censorship, to express critical and independent viewpoints. One such artist, the subject of my scholarship when I was a BU Center for the Humanities faculty fellow in 2017, was Carlfriedrich Claus. He was a kind of utopian communist in the mold of Ernst Bloch, who had no tolerance for the petty corruptions of the GDR state. Claus was extremely well read, drawing insights for his work from sources as varied as the Kabballah, alchemy, Marx, and Bloch himself. He specialized in very delicate poetic pieces, some of which have come to be associated with work by the international network of concrete and visual poets that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. He was also a prolific writer, leaving behind over 22,000 letters and numerous essays. Some of his work takes the form of blending figuration, abstraction, letters and shapes. I am working on a long-term project that seeks to place Claus in dialogue with his contemporary concrete and visual poets in West Germany, Czechoslovakia, France, and Brazil, and other countries. The answer is yes — I work on contemporary art in both the former East and West Germany prior to 1990, though I am still quite new to the burgeoning field of GDR art history.

How does your research inform your undergraduate teaching? Do your graduate students work on the subject matter of your two book projects?

I only teach German art in seminars about once every four years. For the rest of the time I teach on a wide spectrum of contemporary and modern art topics including critical theory, theories of the avant-garde, art and globalization, postwar art in Europe, modern art and comedy, and contemporary exhibition culture. Over the past year, I have had the privilege of supervising excellent PhD dissertations on topics as varied as printmaking in Franco’s Spain, non-profit art spaces in 1970s and 1980s Los Angeles, as well as contemporary art in Poland and Italy. So yes, my general interest in contemporary art informs my teaching. However, because I prefer as much to learn from students as to guide them, I rather enjoy working with students interested in topics that differ from my own scholarly preoccupations.

How have concerns raised by the #BlackLivesMatter and COVID-19 affected you?

As we embark on the brave new world of Learn-from-Anywhere, and as we embrace the urgency of commencing the work of anti-racism, like so many others, I have been engaged in self-reflection and soul-searching both as a scholar and as a member of the History of Art & Architecture department as we explore how best to overhaul our syllabi, curricula, and pedagogies in the interest of greater social equity.

I had intended to use the money from the NEH stipend to fund a summer trip to Germany to do research on Practical Aesthetics. The research was necessary preparation for writing the Introduction and the first chapter of the book. The pandemic has toppled those plans. Fortunately, I had already assembled quite a bit of material that I can put to good use this summer. It is my intention to use the funds instead for a similar trip in the spring of 2021 when I will be on academic leave and when I hope that our world will have reverted to some semblance of normalcy. I hope that any such normalcy would not imply any return to complacency.