Queen Anne Reconsidered

James Winn’s book examines flowering of arts during short 18th-century reign

As a young man, James A. Winn was often advised that he would have to choose. He could be a serious literary scholar or a professional flutist; it was not possible to be both. Winn proved them wrong. He is now a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of English, director of BU’s Center for the Humanities—and a concert flutist and musicologist, with an appointment in the musicology department at the College of Fine Arts.

As a young man, James A. Winn was often advised that he would have to choose. He could be a serious literary scholar or a professional flutist; it was not possible to be both. Winn proved them wrong. He is now a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor, a College of Arts & Sciences professor of English, director of BU’s Center for the Humanities—and a concert flutist and musicologist, with an appointment in the musicology department at the College of Fine Arts.

An expert on English literature of the Restoration and the 18th century, Winn has written several books, among them Unsuspected Eloquence (1981), a history of the relationship between poetry and music; John Dryden and His World (1987), a prize-winning biography of the 17th-century poet (“the most important biography of Dryden ever written,” according to a review in the New York Times Book Review), and The Poetry of War (2008), an examination of the works of artists ranging from Homer to Bruce Springsteen.

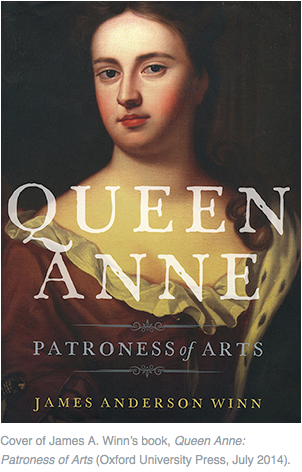

In his most recent book, Queen Anne: Patroness of Arts (Oxford University Press, July 2014), Winn brings together his deep knowledge of both literature and music—as well as the visual arts—to examine the flowering of the arts during Anne’s reign, from 1702 to 1714.

While Anne has often been portrayed as a sad, dull, weak monarch who failed to produce an heir, Winn brings her vividly to life as an accomplished court dancer, harpsichordist, and connoisseur of the arts with an astute understanding of the role that poetry, music, theater, painting, and architecture played in politics and court life.

He also analyzes works by composer George Frideric Handel, poet Alexander Pope, painter Godfrey Kneller, and architect Christopher Wren, as well as anonymous birthday odes, obscene lampoons, and novels about scandal.

With the help of Peter Sykes, chair of the CFA historical performance department and director of BU’s Baroque Orchestra, Winn arranged for a group of Boston musicians to record 28 pieces of music written for Queen Anne, and he has made those works available to readers on his book’s companion website.

Winn’s research for the book was supported by the American Council of Learned Societies, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

BU Today talked with Winn about why he thinks Queen Anne has been overlooked by other historians, his advocacy for an interdisciplinary approach to the humanities, and the importance of writing for a broad audience.

BU Today: Your preface quotes a 19th-century Victorian writer and editor describing Anne as “ugly, corpulent, gouty, sluggish, a glutton and a tippler.” Why were other historians were so dismissive of her? Did you set out to rescue her?

BU Today: Your preface quotes a 19th-century Victorian writer and editor describing Anne as “ugly, corpulent, gouty, sluggish, a glutton and a tippler.” Why were other historians were so dismissive of her? Did you set out to rescue her?

Winn: Queen Anne has certainly not gotten much credit for being effective as a monarch, which she was, as popular, which she certainly was, and as astute, which almost no one recognizes she was—or, for that matter, as well-informed about the culture and arts, which she was.

I think her size is part of that. It’s a sad truth that I think people look at the portraits of her and read about her and make that leap—“fat, therefore stupid.”

Why have historians emphasized her size? Who cares?

My colleague at Loyola, Robert Bucholz, a court historian, has a fine essay about Anne’s body [“The Stomach of a Queen or Size Matters: Gender, Body Image, and the Historical Reputation of Queen Anne”]. He says, and I agree with him, that you can tell a lot about a historian’s attitude toward Anne by the words he or she uses to describe her body. If they say “gross,” “obese,” “fat,” then they’re hostile to Anne. If they say “plump,” “maternal,” etc., then maybe they’re not quite as hostile.

Look, she was large, but let’s remember that there’s a double standard here. Certainly in the 18th century, lots of men were huge. Robert Walpole, the prime minister, ruled England for 40 years as the most powerful person in the country. He was enormously fat. There were portraits of him—he could barely button his vest. That doesn’t seem to have been a problem for him, but for poor Anne, especially starting in the 19th century, this got to be a mark against her.

Then, of course, there was her gender. Now you can say, and it was true, that Elizabeth I enjoys a big reputation—a queen who understood power, a queen who defeated the Spanish Armada, who accomplished all these things, and Victoria has pretty good press, but somehow in between them, Anne has not gotten much attention.

I started out thinking about this book as being about the extraordinary flowering of culture that occurred during the 12 years of her reign. And then my hypothesis was, “Surely the queen had something to do with this”—because there wasn’t yet a sustaining commercial system that would have explained why these people were able to make the literature and painting and architecture and music that they made.

So I went looking for “What does Anne know about the arts and does she, in fact, care? Was there a way she was making choices or funneling money to people or in general making the arts happen?” And I found a lot.

You write about the role of the arts in these elaborate court rituals—like birthday parties. Anne had to plan a birthday party for King William, whom she didn’t like.

With good reason.

You write about how she had to plan this party and maybe she’ll arrange for a play to be put on, and she writes a letter to her good friend Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough.

She writes, “I have been told the king does not care for plays.” It’s such a wonderful piece of irony. She knows perfectly well that he’s never gone to the theater in his entire reign. He’s a soldier; he doesn’t care about the arts. But there has got to be either a ball where people learn an elaborate new dance, which is trouble, or they can bring in one of the theater companies and they’ll just put on a play. Because Mary has died, Anne is now the official hostess for these events. She’s trying to think what to do, so she writes this letter to Sarah. It’s just a big private yuck between the two of them.

It’s so dry.

That’s the way she is. That’s why her sense of humor has been missed—because it tends to be understated and ironic like that.

It sounds like you really came to like and respect her.

I did. I see her weaknesses and I see the pathos of her life and the way people kept trying to manipulate her, but I think she showed courage and a profound sense of duty. She could have blown off being queen…and let the men run it. To some extent, some historical accounts of Anne claim that’s what she did, but it’s a bogus claim. She attended more meetings of the Privy Council and of the Treasury board than any monarch of her era.

Her uncle Charles couldn’t be bothered to go to the meetings of the Treasury board. He was going to the play or hanging out with his mistresses. She was very conscientious, and again, you miss that in the kind of breezy dismissal by people who should know better.

Are these people who should know better mostly male historians?

You know, I have to say she’s a ripe topic for feminists, and it’s interesting they haven’t picked up on her.

You get into Anne and some of the gender politics of the time in your book.

Yes, there’s a wonderful moment—there’s a French marquis who’s been captured; he’s in the tower, he’s a prisoner of war. They do prisoner exchanges regularly through the course of the War of the Spanish Succession—this long war they fought against the French. Luttrell, the diarist, reports they were going to exchange him for the daughter of the English consul who’d been captured at Leghorn by the French. But he didn’t want to be exchanged for a woman. And so Anne says, “Fine, you can stay in jail. You think it’s beneath you to be exchanged for the daughter of a diplomat? You can hang in the tower for a while and see how you feel about that.”

Did other people see this correspondence and just overlook it?

You see what you want to see. Absolutely other scholars have read the letters, but everyone comes to even a body of archival material with their own prejudices, their own aims and goals. So what am I looking for? Well, above all else, I’m looking for her to say somebody came and sang for her at court and had a beautiful voice or that she doesn’t want to buy a painting that’s been offered to her or she has or hasn’t read a particular book. All those things appear. Somebody whose particular keen interest is in diplomacy would be looking for all references to the King of Denmark or something like that.

Why are the arts a valuable lens through which to look at history?

If the story we tell ourselves about the past is only about money and power, then we have very little access to how it felt to live at that time, whether that time is the Middle Ages in France or 18th-century England or 19th-century Japan. If our account of history censors, omits, leaves out, obliterates the arts, we’re certainly falsifying the past, and one way of putting this that almost everyone can understand is that we’re especially falsifying people’s emotions.

The arts are a complex and sophisticated way of expressing, among other things, emotions. It’s been my drive throughout my teaching career and throughout my writing career to try to see some pieces of history whole, or as whole as I can.

Was this way of thinking inspired by one of your teachers early on or does it come from the fact that you’re a literary scholar—and an accomplished musician—yourself?

The moment for me that I often think about—which was a moment of personal advice, not of intellectual content—happened in my freshman year in college. I was 17, just off the Greyhound bus from Kentucky, eager and naïve, and I had the good fortune to have as my faculty advisor a 29-year-old assistant professor named Robert Freeman, who went on to become for 30 years the head of the Eastman School of Music and then for 10 years the dean of fine arts at UT-Austin. A wonderful man.

I said to him, “Do you think it would be possible for me—not only here at Princeton as an undergraduate, but in life—to be both a serious student of literature and a serious flute player?”

And he rocked back in his chair and said, “Why not?” And that “Why not?” has sustained me for about 50 years now, because he believed I could do it. Many other people at later stages of my career urged me in quite specific terms to give up one or the other. They would say, “You play the flute well enough to do it, why are you messing about getting a PhD,” or they’d say, “This is for serious scholars, you can’t waste it on playing the flute every day.”

So it is the case that I have had two careers, as you can tell by looking at my schizophrenic website. And because of that, I think I have been more open to the idea of looking at the past through more than one lens and trying to bring together what are normally thought of as materials pursued by one or another discipline and to bring them into conversation with each other.

You’ve devoted your life to the humanities, but funding cuts and dropping enrollments have changed things. You spoke at the University of Connecticut, urging scholars to make the case for the value of the humanities.

I don’t think the right strategy for us as humanities faculty at a major research university is to fold our tents or to fall back on whining. I think we need to be supple and nimble and creative. We need to try to find ways to dramatize what we teach and why it’s important for today’s students. We need to remind our students, our colleagues, and the wider world of the function of the humanities, the study of what my theologian father once called “the wonder and worry of being human.

It’s really hard to get research money in the humanities today.

You apply for a grant to the National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH), the hit rate is six percent. We’re trying to train the faculty that you don’t always win the NEH, but also how you win. You don’t write a grant proposal that makes sense to only the four other people in your subfield.

Right now, I am Mr. Broad Appeal. It’s something I’m able to do here with our resident humanities fellows. We have a seminar where they read each other’s works in progress. I tell them, “If you can’t write a chapter that the other eight people here are interested in, you’re in trouble.” You might be in religion, they might be in anthropology, but you want to write something that’s at least of interest to other bright scholars, let alone the larger public.

Why do some people in academia seem to write only for other people in their disciplines?

They’re marinated in their discipline. Some people never come up for air and shrug it off. It’s partly the system—peer-reviewed journals, the damn tenure process. By the time you get tenure, which takes longer and is farther out than it used to be, your first book is on the early Byzantine arch. Your second book is on the later Byzantine arch. Then you write a bunch of scholarly articles about special features of the Byzantine arch. It’s not everybody else’s fault that we have less of a public than we used to, and it has everything to do with why we don’t have the funding we do. We need popularizers and people in academia fear popularizers. They fear they’ll be superficial and they’ll just do bumper stickers. My friend Simon Schama, I think he’s done a world of good for history.

What other popularizers from academia do you admire?

Skip Gates—he was my colleague at Yale. Stephen Greenblatt. Jill Lepore. These are crossover artists. They are people who teach at a university, but can actually write an article in the New Yorker. We need more of that. Every time something like this happens, it’s good for the humanities. Right here at BU, my colleague Stephen Prothero has engaged a national audience in thinking about images of Jesus, and my colleague Charles Griswold has written a philosophical book about forgiveness, something we all need to consider at one time or another.

Watch video interviews with James A. Winn about Queen Anne posted by Oxford University Press:

- On the intelligence and good taste of Queen Anne.

- On the importance of looking at Queen Anne through the arts.

- How did Queen Anne support the arts?

Listen to James A. Winn’s solo performance of the Bach partita for flute at Marsh Chapel in October 2014.

A version of this story originally appeared on the BU Research website.

Author, Sara Rimer can be reached at srimer@bu.edu.