Boston Art Review feature: Photography Into Palimpsest, In Conversation with Toni Pepe

Toni Pepe inside her Malden studio. Photo by Carlie Febo for Boston Art Review.

Boston Art Review feature: Photography Into Palimpsest, In Conversation with Toni Pepe

This interview was first published in the Boston Art Review on December 19, 2022. By Michelle Millar Fisher

Toni Pepe is an Assistant Professor of Art, Photography, and Chair of the Department of Photography at BU School of Visual Arts.

Excerpt

Toni Pepe is a visual artist deeply curious about how photography shapes lived experience. I was fortunate enough to visit with her on a sweltering day in August when she opened her shaded home studio, cracked open cold seltzers for us, and showed me the work she’d been preparing for an upcoming exhibition at the Danforth Art Museum at Framingham State University (“Toni Pepe: Ordinary Devotion,” on view through January 29, 2023). What follows is a condensed version of the day’s conversation.

I was first drawn to Toni’s work because of my own research around how art and design meets the arc of human reproduction, historically and today. My interests resulted in a book and an exhibition, Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births, on which I collaborated with another wonderful design historian and a team of brilliant colleagues. Toni’s oeuvre doesn’t only focus on motherhood, but a substantial part of it does. So, we had a lot to talk about.

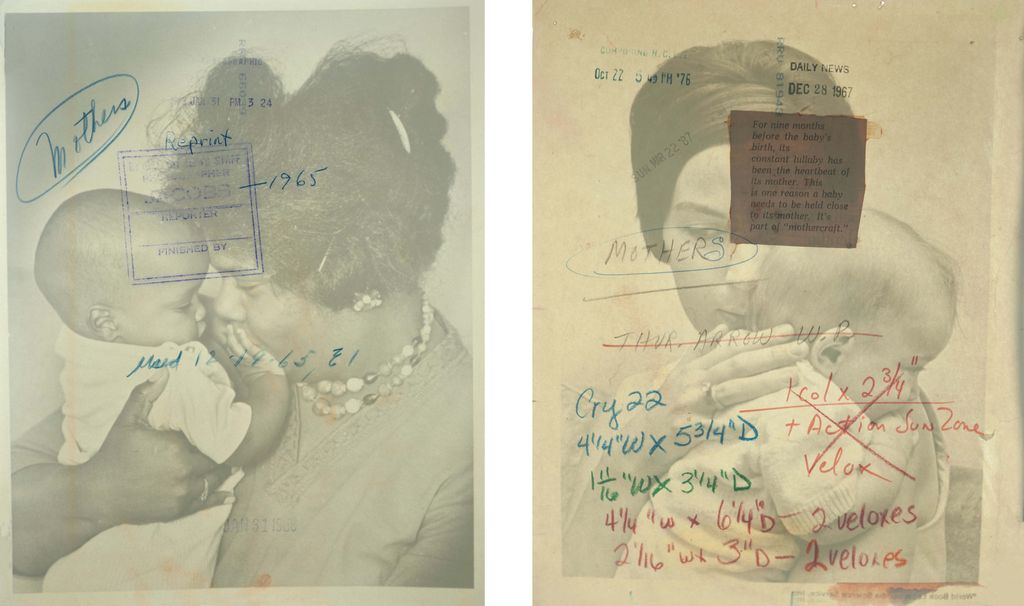

Toni’s work is the closest I’ve seen photography get to sculpture and installation. Her approach to the medium is multifaceted. Sometimes she’ll shine a strong light through an archival photograph that she’s found on eBay or in a library collection such that, when she re-photographs it, she captures both the image on the front and the marginalia scribbled and stamped on the back. At other times, she’ll arrange found photographs—including glass slides, negatives, and prints curled at the edges that look like they’ve been torn from someone else’s family album—in constellations held in place with prism slivers and telescopic lenses. Another approach etches found images onto glass and, using projected light, enlarges them as shadows on a wall. The result in each case is a palimpsest that turns image into object, recasting our relationship to it.

Both Toni and I are drawn to the topic of motherhood not because of any shared biology, but because it has historically been seen as marginal, taboo, and unworthy of sustained scholarly attention. We’re interested in the everyday, and we find richness in things that patriarchal, racialized socio-economic structures have resisted interrogating. I think we both enjoy doing work we’ve been told we’re not supposed to, and finding kinship in the very many people whose lives have been touched by reproduction, birth, pregnancy, and postpartum. After all, it’s how we all got here in the first place.

Fisher: For those who do not know your practice, can you introduce it?

Pepe: In my work, I think specifically about our experiences of time and space—how a photograph compresses, distorts, and manipulates them, and how a photograph shapes our sense of self, both individually and collectively. What does it mean to look back at yourself and others repeatedly and from seemingly innumerable perspectives? And how does photography ground identity but then also splinter it? For the past ten years, my work has focused on motherhood and caretaking more broadly. In my practice, I allow my ideas to lead me toward materials or a particular process—and I use a range, from archival photographs, found family photographs, and laser etching to mold making and traditional photographic processes like cyanotype or digital capture. I want to illustrate the complexity of care.

Fisher: That leads perfectly to my second question. The theme for this issue of BAR is burnout. It’s a term that has proliferated in use over the last couple of years. What does that term mean to you personally and professionally?

Pepe: For me, burnout doesn’t necessarily compartmentalize into professional and personal. It’s really about that push and pull between the two. I find the most fulfillment in my role as a mother alongside my role as an artist and educator. These roles come with many demands on my time, body, and emotions. I think a lot about the early years of parenthood; they’re incredibly physically and emotionally taxing. At that point, burnout just felt inevitable to me—all those sleepless nights. I wish I could go back in time and just be kinder to myself, telling myself, “You’ll get through it.” Now, I think less about each task having some sort of finish line. I think that’s what led to some of my burnouts; I felt like, “Oh, if I just finished this one thing, then I’ll be done.” But caretaking and art making are similar in that they’re never done. They’re endless. That finish line is an illusion. And I wouldn’t want them to be done; they’re a critical part of my humanity.

Fisher: Can you talk a little bit about your Mothercraft series, which is what we initially bonded over? How and why did you come to this work?

Pepe: Mothercraft is an ongoing body of work in which I’m using press photographs that I have found at flea markets or through deep dives on eBay. I’m using them to reconsider twentieth-century depictions of mothers in the US media. I initially came to this work after being asked to participate in the Yellow Rose Project, a photography-based collaboration amongst one hundred artists across the US that responded to the centennial of the nineteenth amendment. That shifted my focus from family albums or vernacular photographs to press photographs, and I became more interested in public-facing images of women. The images I found ranged from the invention of the birth control pill to Mussolini on a balcony, giving a fascist speech praising the mothers of Italy for strengthening the country because they’re giving birth.

I’m attracted to old things that are used and marked by time. And some of these press photographs are just falling apart. They are objects in their own right—dirty, stained, marked, and layered. Much of that attraction comes from growing up with a father who worked with his hands and could fix anything. His garage is a lot like my studio; it’s just filled with objects that someone else deemed obsolete, but they would eventually find a new life and a new purpose in his hands. I always really admired that. In my studio, you’ll see similar things, too: a broken slide, or glass negative, or bits and pieces of a photograph, things that might appear to be trash, or were things that people just abandoned, but I take them in, and I’m hoping to give them a new life, to really show that their story isn’t done, that there’s some sort of legacy there to be recognized.