Kirsten Greenidge included in POLITICO Magazine: “What George Floyd Changed”

This article was first published in POLITICO Magazine on May 23, 2021.

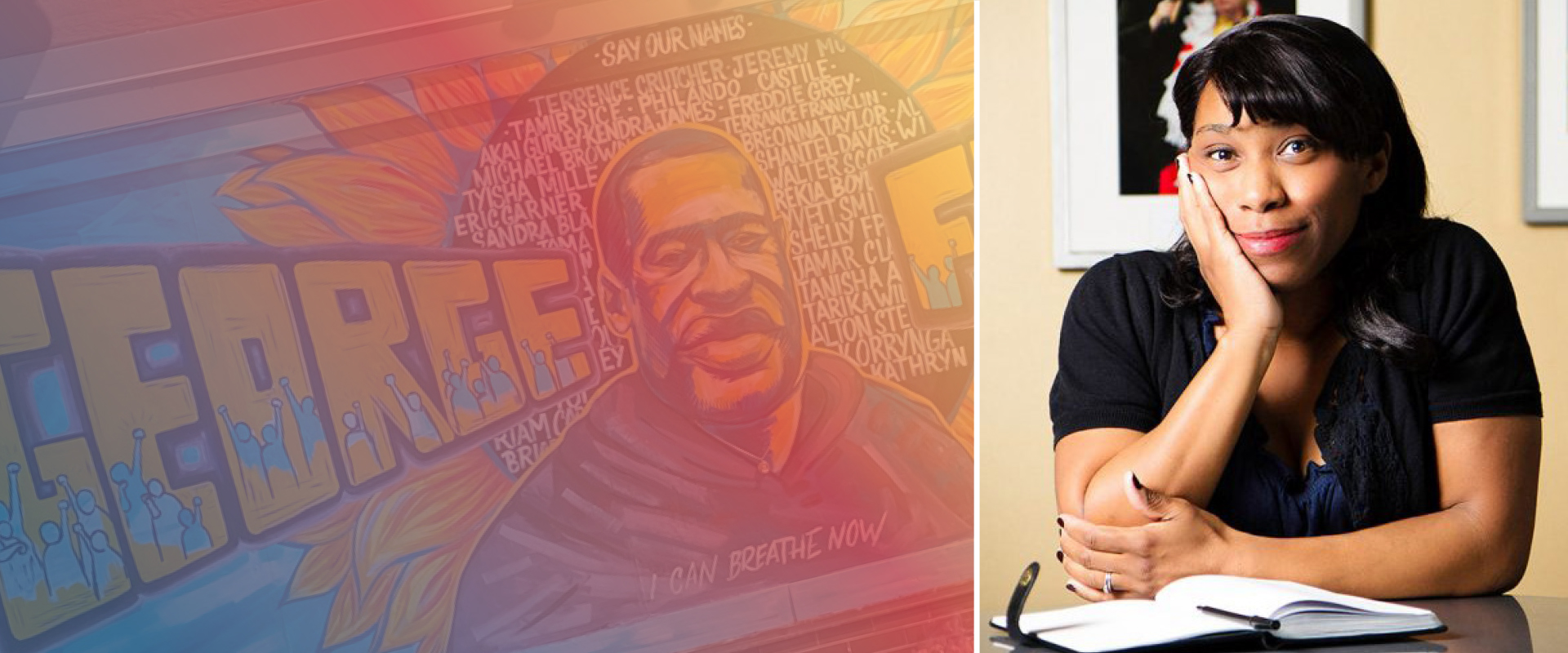

What George Floyd Changed

The protests over one man’s death touched far more aspects of American life than just criminal justice. Seven thinkers reflect on how America is (and isn’t) different now.

EXCERPT

In the year since George Floyd died under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer, the explosive waves of national protest that followed have taken on almost a settled meaning: They were calls for police reform, and for America to take a hard look at the racial injustice threaded through its civic life.

But in its breadth and impact, the reaction to Floyd’s killing also blew through any conventional expectations for what a “protest” might touch. The reckoning it prompted about race in America extended to workplaces, classrooms, legislatures; it shook the worlds of art, literature and media. Americans began to talk about their own history differently. They physically pulled down monuments. The waves crashed against the fence of the White House, and rippled overseas.

POLITICO Magazine asked a range of thinkers to reflect on the surprising ways that Floyd’s death reshaped the country—and what hasn’t changed, too. They noted that many Americans, including political leaders, now talk about race and racism in blunter, more honest ways, and are more willing to rethink the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. Some cities are physically different, perhaps permanently.

Of course, in some cases, they said, the way we talk might be all that’s changed, and not so much the way we act. A year later, a police officer is guilty of murder, but Black people have continued to die. And the next chapter has yet to be written.

…

At BU, Kirsten Greenidge teaches Ensemble I: Introduction to Playwriting with first years, Adaptation for sophomores, and Playwriting Colloquium with seniors. She is the recipient of a Village Voice Obie Award for her play MILK LIKE SUGAR, which was commissioned by La Jolla Playhouse and Theatre Masters, and co-produced by La Jolla Playhouse, Playwrights Horizons, and WP Theatre. MILK LIKE SUGAR has also received a Lucille Lortel nomination, an AUDELCO nomination, and an Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE) Award. Other plays include THE LUCK OF THE IRISH, originally produced by the Huntington Theatre Company; BALTIMORE, which is the product of a Big 10 Consortium Commission, a program created to address the lack of roles for female BFA candidates; ZENITH, most recently produced by San Francisco Playhouse’s Sandbox Series; BUD NOT BUDDY with music by Terence Blanchard (Kennedy Center; Metro Stage); BOSSA NOVA (Yale Rep); SPLENDOR (Company One Theatre Company); and SANS-CULOTTES IN THE PROMISED LAND (Humana Festival/Actors Theatre of Louisville). Learn more about Kirsten Greenidge and playwriting at BU.