Getting Animated

Mai-Han Nguyen turned her love of drawing and printmaking into a career at Nickelodeon

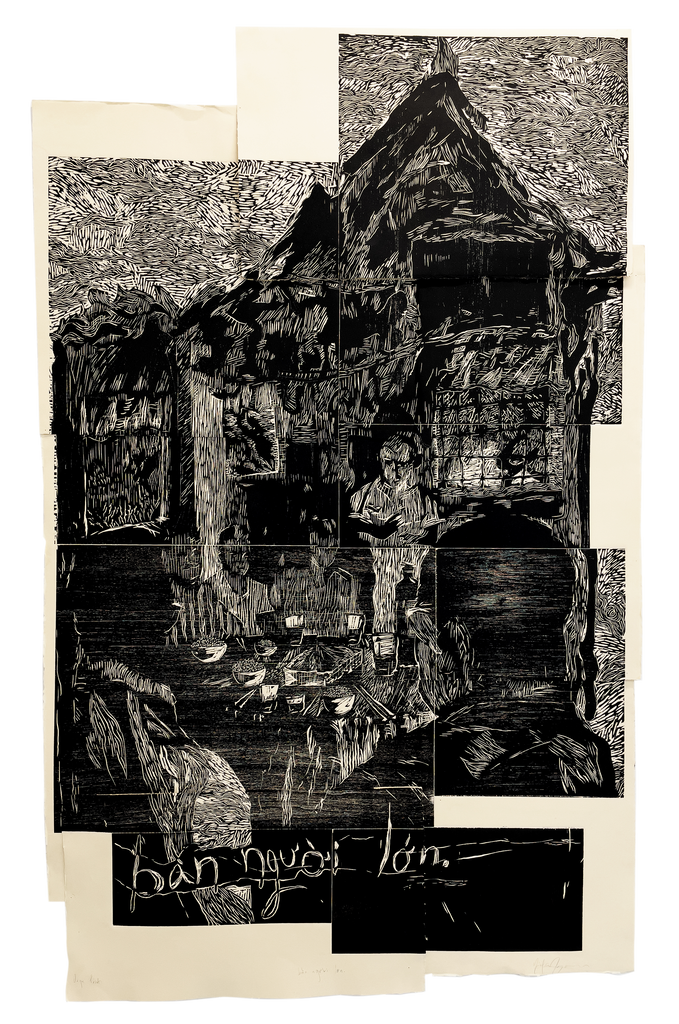

One of Mai-Han Nguyen’s personal story concepts imagines World War II in a sci-fi fantasy universe filled with airships shaped like giant fish. Images courtesy of Mai-Han Nguyen

Getting Animated

Mai-Han Nguyen turned her love of drawing and printmaking into a career at Nickelodeon

As a printmaking major at CFA, Mai-Han Nguyen began every new project the same way—with a handwritten checklist outlining every step of the process. Not exactly glamorous, but precision was critical when it came to mixing pigments or concocting an acid bath to properly etch a metal plate.

It’s a routine Nguyen (’21) brought with her to Nickelodeon Animation Studio, where she is a full-time visual development artist. These days, instead of ink and acid baths, she’s keeping track of file dimensions and organizing her layers in Photoshop. “A lot of the habits that I have in my work now come from printmaking,” she says.

At first glance, printmaking and animation might not appear to have much in common. Printmaking goes back centuries, with some of the earliest examples of woodblock prints dating to Japan, circa 700. Animation, depending on who you ask, got its start in 1892 with Émile Reynaud’s film Pauvre Pierrot or 1908 with Émile Cohl’s Fantasmagorie. Printmaking is a physical, tactile process that can be done by a single artist, while 21st-century animation happens primarily in the digital realm and is almost always a team effort.

But for Ngyuen, printmaking was key to unlocking the skills that she uses daily at Nickelodeon.

“There’s an exactness to both,” she says. “That’s the throughline that I really like.”

THE DRAW OF ART

Growing up, Nguyen was made to understand that art was a hobby, not a career. “I always remembered my grandparents and everyone in my family talking about how there’s this artistic inclination that runs in the family, in every generation,” she says. “My grandfather had it before he came to the US—even back when he was in Vietnam. But because we weren’t wealthy, he couldn’t give art much of his attention.”

Nguyen didn’t take her first art class—introduction to drawing—until high school. Her work drew the attention of the head of the department, Michelle Cobb, who asked her whether she’d considered pursuing art professionally.

When Nguyen told her she planned on majoring in environmental science, Cobb urged her to think about it. “You can go down this path that you think is right, or you can take a chance,” Nguyen recalls her saying. And suddenly, Nguyen was crying. “I broke down in the middle of the art studios,” she says. “Anyone could have walked in, and I’d be sobbing hysterically. That almost emotional breakdown solidified that there was this lingering regret inside me that I was trying not to acknowledge.”

She made up her mind: she would study art in college, a choice her family greeted with some resistance. “I just bulldozed ahead through that,” she says. “I made the decision that there will always be time to redirect my path if I need to. But at least in this moment, this is what I wanted to do.”

As a printmaking major at CFA, Nguyen experimented with wood cut prints, watercolor monotype, lithography, etching, and other disciplines.

As a compromise, she enrolled in a dual degree program in painting and environmental science at BU. Sophomore year, she studied abroad in Venice, where she took her first printmaking course, at the local Academy of Fine Arts. “It blew me away,” she says. “The studio equipment is too expensive not to be shared, creating an extremely collaborative environment. Everyone’s constantly sharing knowledge about how to use certain tools or certain chemicals. I really fell for that atmosphere.”

For most people, freedom means fewer rules. But for Ngyuen, the strict guidelines around the printmaking process unlocked her creativity in ways that a more open-ended artistic practice wasn’t able to do. “I loved learning about the restrictions within certain materials,” she says. “Having these limitations made me feel like I was more able to come up with my own ideas and concepts. It really suited me really well. I found a lot of freedom in that guidance.”

Upon her return to campus, she officially switched from painting to printmaking—and dropped environmental science. She likely would have sought an internship at a printmaking studio after graduation, if it hadn’t been for the pandemic. The lockdown gave her time to consider what she wanted to do next. “The printmaking studio itself was collaborative,” she says, “and that was great. But I kept thinking that I wanted to work with more people —not just from the US, but from around the world—on projects that were bigger than just what was in front of me.”

She explored other artistic disciplines and found the Creative Talent Network (CTN), an animation organization that hosts an annual expo. In 2021, the event offered online-only tickets, allowing her a convenient way to dip her toe into the world of animation. And what she discovered fascinated her.

THE ANIMATION PIPELINE

Animation is a hugely complex undertaking, with dozens or even hundreds of artists working on a single project—from character design to color palettes to storyboarding. Visual development artists (also referred to as “concept artists”) are one link in that chain. Their job is typically to bring the world to life based on the animatics—a story-board in motion, essentially—by filling in the details.

“You’re helping someone else visualize that idea in their head that they can’t really see yet,” Nguyen explains. “So it’s all these abstract ideas, and it’s your job to take those ideas and make them into a tangible reality. You have to convince an audience that this is something that can exist.”

That’s where research comes in. References are critical to understand how everything works, even the more fantastical elements. “It’s very easy to draw a car, but in order to make that car look specific to the world, you have to know which parts you can manipulate and which you can take out,” says Nguyen. “And that theory is applied to everything in the world—you have to know how it works in order to take it apart and make it into something that fits.”

Through CTN, she found out about a real-world production pipeline class run by James Lopez, a veteran animator at Disney. The project the class would be working on was Cowabunga, a four-minute short chronicling an alien ship’s madcap attempt to abduct a feisty bovine. Nguyen applied for the production stage, and spent six months filling in the details of the world that had already been storyboarded by the previous cohort—from the shape of the grass to the style of fencing used on the farm.

Cowabunga “has a special place in my heart,” Nguyen says. “All of us were so new to the industry at that point. It was the first time I got to work with other people on anything similar to an animation pipeline. I realized how much effort it took. It was definitely stressful, but seeing it come together was kind of like my test. Being a part of that production was trying to see if this was something that I wanted to do as a career.”

The answer was clear. Now, she just needed to find a job. After completing Cowabunga, she freelanced on two more projects—one with a studio in Singapore, on a film set in 1941 during Japanese occupation; another with a studio based in Germany, about a baby Loch Ness monster—and participated in a mentorship program through the nonprofit Women in Animation with an animator from Dreamworks. She worked on her own concepts too, like an alternate version of World War II, where humankind has bioengineered airships out of gigantic fish.

In late 2023, she learned that she’d been accepted into the visual development track of Nickelodeon’s 2024 artist program for emerging talent—a highly competitive role. “It’s always been the timing for me,” she says, of landing the gig. “A lot of it is being able to have your skills up to where they need to be at the time that that job needs them.”

THE NICKELODEON EXPERIENCE

The six-month artist program at Nickelodeon is more than an internship. Everyone accepted is embedded with an existing team of full-time staff, working on a real-life animation project. In Nguyen’s case, that was Avatar: Seven Havens, a highly-anticipated sequel series to the beloved 2000s cult classic Avatar: The Last Airbender, helmed by the original creators, Michael DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko. When the program ended in June 2024, Nguyen was offered a full-time job as a background design artist with the team, working remotely from her hometown of Washington, D.C.

She works long days, often close to eight hours of uninterrupted drawing. “There are a bunch of people that have to review that shot and make sure it aligns with what they’re imagining for it,” she says. “It’s a lot of back and forth.”

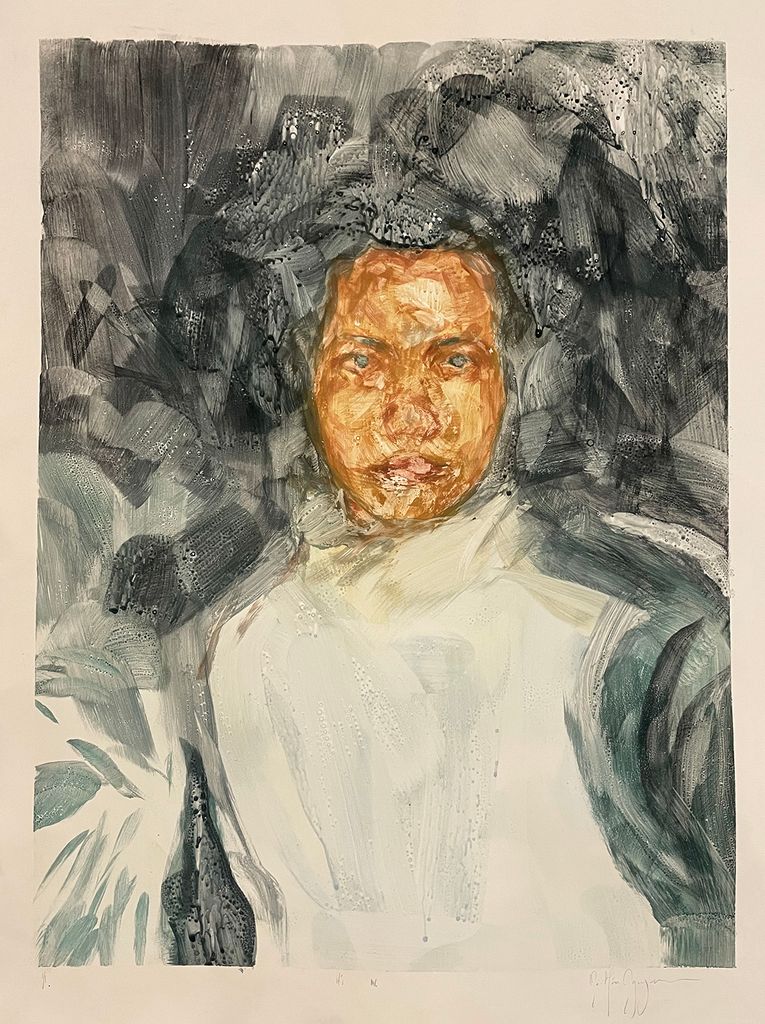

As a visual development artist, Nguyen creates detailed reference works that help bring the story concepts to life.

The process doesn’t faze Nguyen, though. “I come from a fine arts background, and so we get a lot of critiques—really, really hard critiques,” she says. “You have to be able to take any notes that you’re given and translate it into what you think they want, which is tricky, but also it’s my favorite part about the job. I think the back-and-forth is what makes it so interesting. It feels like a challenge.” For Nguyen, it’s a dream job. “I have everything I want,” she says. “I get to work in art and make a living at it. High-school me would not have thought this would be possible.”