Felt, with Feeling

Elizabeth Stubbs uses wool to bring magical scenes—and the occasional political bogeyman—to life

Photos by Simon Simard

Felt, with Feeling

Elizabeth Stubbs uses wool to bring magical scenes—and the occasional political bogeyman—to life

Felt was one of humankind’s first textiles. The nonwoven fabric, typically made from wool, is so durable it’s been used for millennia to make shoes, yurts, and even armor. The oldest known example, however, was decorative: a wall hanging from 6500 BC Turkey.

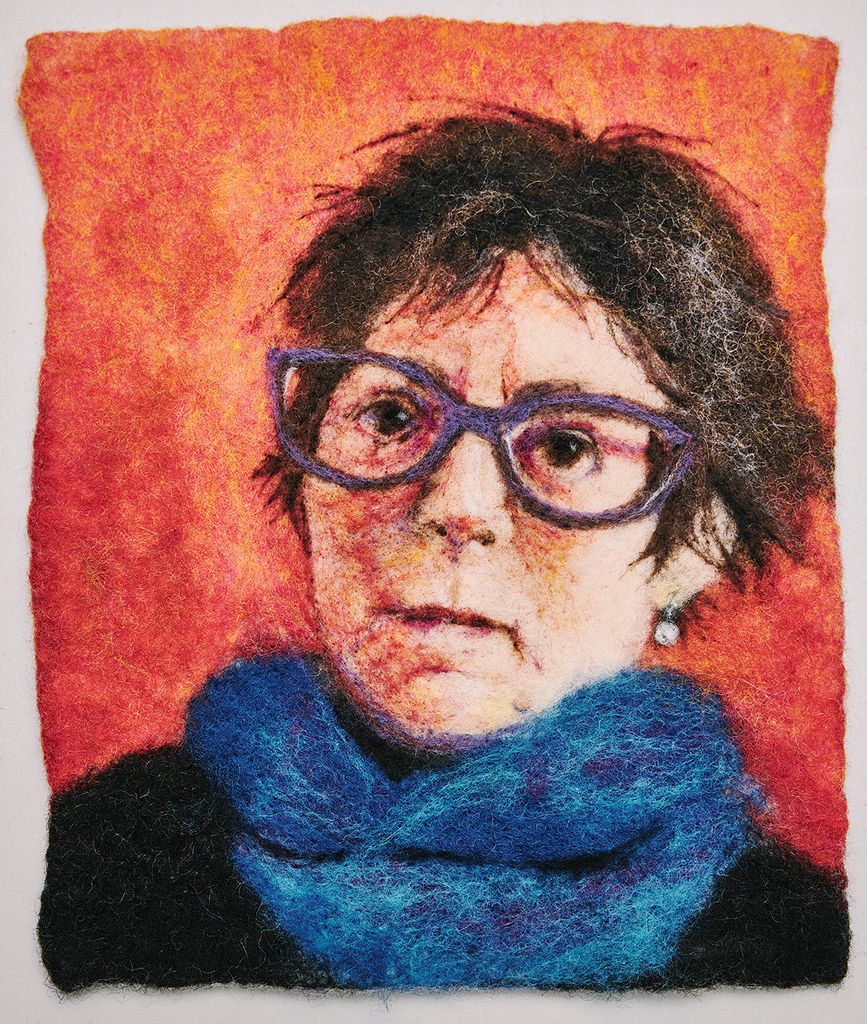

Elizabeth Stubbs has been creating art with felt since 1997, when she was training as a Waldorf early childhood educator. Waldorf philosophy prioritizes art and the use of natural materials. “The whole idea is that the children take substances and transform them into other things—and wool is an excellent substance to transform into other things,” she says. Stubbs (’74), who had worked as a painter and an illustrator for more than two decades, has worked with wool ever since, creating landscape “paintings,” sculptures, and vessels.

“It’s amazing to touch,” she says. “That tactile quality is extremely appealing. It’s very earthy and has a distant connection with other cultures and other times.”

Stubbs typically uses a wet felting technique. Working on a granite counter in her basement studio, she lays different shades of wool in layers, building an image from background to foreground. To turn wool into felt, she sprays it with a shower of soapy water. That opens the scales along each fiber, which then entwine and lock the wool together as she agitates it by rolling it vigorously with a piece of foam pipe insulation.

“All these little wisps of wool melt into one another so they are suddenly on one plane,” she says. “You never know exactly how that’s going to go. I love that element of surprise.”

Once the wet felting is complete, Stubbs often does needle felting—repeated stabs with a barbed needle that bonds the fibers—to add details to her work.

Stubbs guesses that she has 50 pounds of wool in her studio but only needs 3 to 4 ounces to create an image. She prefers working with Merino wool, from humanely raised sheep, because it felts more easily than coarser varieties.

Many of Stubbs’ pieces are inspired by nature, and she uses dozens of colors to create them, from deep blues and purples to earthy oranges and browns. Some of her most striking works are landscapes.

It’s amazing to touch. That tactile quality is extremely appealing. It’s very earthy and has a distant connection with other cultures and other times.

“Wool is sort of blurry and doesn’t lend itself to a lot of small details,” she says. And yet, she expertly uses the tiniest splashes of yellow to capture autumn leaves falling to the ground and dark greens to create crisp shadows across a field. The use of different wool fibers, laid out in layers and felted together, creates the sense of an image constructed from a group of distinct objects, part sculpture, part painting. Stubbs often combines several prefelts—small pieces of partial felt—into larger scenes. She compares this process to that of Eric Carle, the late children’s book author and illustrator, who created characters like Very Hungry Caterpillar and Brown Bear with vivid tissue paper collages.

Left: Allegory: Garden of Good and Evil (2022) 33 x 31 in. Right: Birches by the Water (2021) 9 x 10 in.

In a landscape she completed during the COVID-19 pandemic, Stubbs used a blend of blue, purple, and white to create a sky. A creamy yellow wool gives a warm glow to sun rays reflecting off a river. Orange and brown reeds, which she needled on after finishing the wet felting, define the foreground. Birch trees with white bark crisscrossed by delicately needled black lenticels split the right side of the frame.

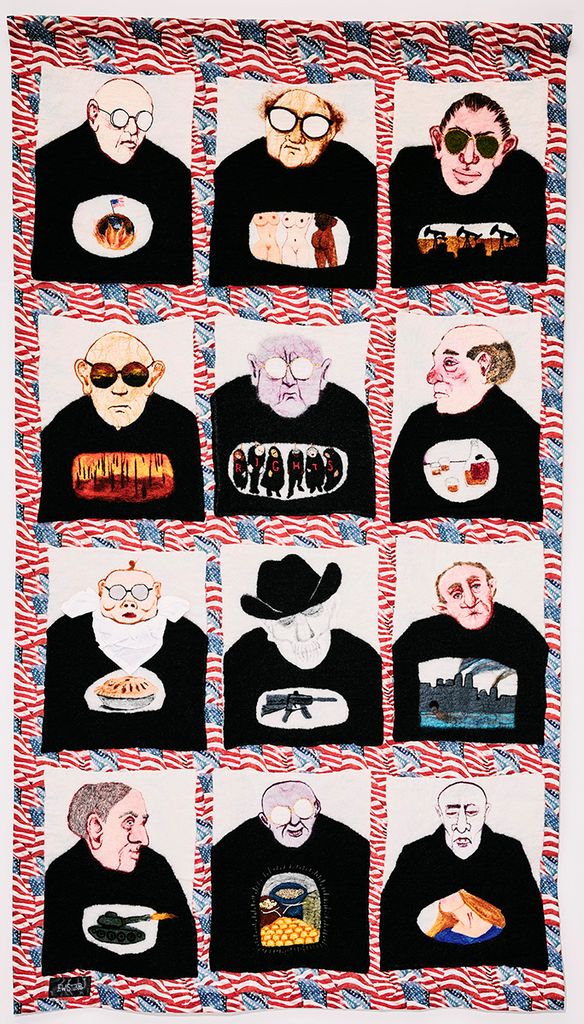

Another inspiration for Stubbs’ work has taken on more and more prominence lately: politics. “Every day there’s some new outrage,” she says. “It makes me sick. I have to get it out somehow.”

One of Stubbs’ largest pieces, completed in April 2024 after two years of work, features a series of individually felted figures stitched to an American flag backdrop. The 68-by-37-inch Patriarchy includes images of a dozen ghoulish men, each with an image on his chest that represents what Stubbs calls “a window into his soul.” One profits from war, one covets women. One of the men “wants all the pie,” she says. “I have been constantly shocked at the behavior of those who seek to be in power. The selfish pursuit of money and power—at the expense of the environment and all human rights—is really beyond my comprehension.”

Stubbs explored that intersection in This Land is YOUR Land?, which she created for Ribbon of Highway, a November 2024 exhibition by the Northeast Feltmakers Guild in Basking Ridge, N.J. Artists were given a strip of gray gauze and instructed to use it as the highway from Woody Guthrie’s folk song “This Land is Your Land.” Stubbs’ 18-by-24-inch piece shows a group of animals, from a tiny turtle to a bull moose, locked in a standoff with a truck. She created each animal separately and sewed them to a wet-felted background. She needle felted details to the truck and used locks from a blue-faced Leicester sheep—known for their fine, curly hair—to create the foliage on a copse of trees in the center of the image. The finished piece is bright and cheerful, despite the tension of the human–animal conflict. “I think the world needs beautiful pictures,” she says.