Our Fragmented Selves

Hoda Kashiha’s paintings depict gender politics with cartoonish flair, tongue-in-cheek humor, and a relentless urge to experiment

In Appreciation of Blinking (2021) Acrylic, silkscreen print, and wood glue on canvas (set of eight works); each canvas 83 x 69 in. All images courtesy of Kashiha

Our Fragmented Selves

Hoda Kashiha’s paintings depict gender politics with cartoonish flair, tongue-in-cheek humor, and a relentless urge to experiment

How does artist Hoda Kashiha find humor in her work? The Iranian national lives and paints in a suburb just outside of Tehran, the capital of a country that has grappled with decades of gender inequality. Since 1983, women in Iran have been mandated to cover their hair with hijabs or face jail time, and a morality police force was established in 2005 to enforce modest dress, among other strictures. An Iranian woman’s body is a highly politicized landscape, and attempts to flout convention can incur serious penalties.

Yet women’s bodies are front and center in Kashiha’s works—breasts, legs, buttocks, genitalia, and all. They are sometimes rendered in jagged, cartoonish strokes, often accompanied by a leering or condemnatory male presence—a garish reminder of the spaces where women’s rights are restricted.

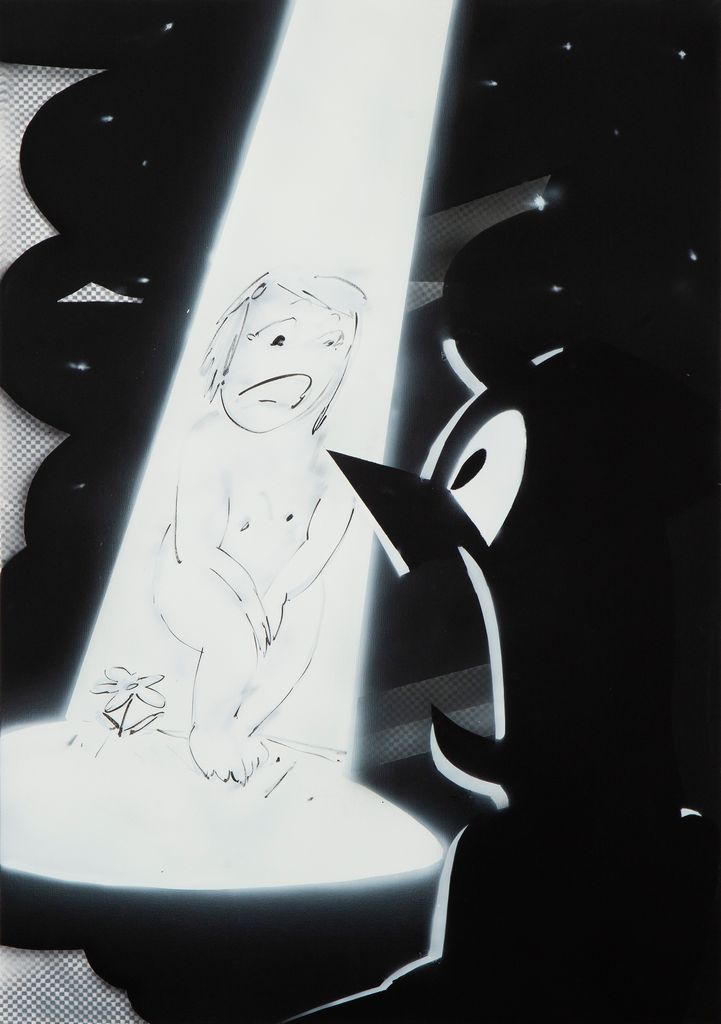

Much of the flamboyance in her work is an overture to something a little darker. Spotlight shows a black-and-white nightmare scene where a woman, trapped in a harsh white stagelight, attempts to shield her nakedness from a man whose shrieking face takes up most of the foreground. She’s rendered like a notebook doodle; he, with his upturned nose and bulging eyes, looks a bit like a Looney Tunes character. She’s vulnerable; he’s outraged.

The deconstructive tangle of body parts, the gawking eyes, the boldness of depicting this in the first place—is there any levity to be found in this message, at a time like this?

“Lots of tragic things have happened in our culture, but we always joke about them because it chills the situation and relaxes you,” says Kashiha (’14), a graduate of CFA’s MFA program in painting. “At least you can laugh.”

Left: Water Like Mirror Hugged My Profile Face in the Red Hot Sky and Now My Full Portrait is Unveiled in the Soaked Chilled Sky (2023) Acrylic on canvas and steel structure; 39 × 47 in. Right: Spotlight (2020) Acrylic on canvas; 39 x 27 in.

From Tehran to Comm Ave and Back Again

Kashiha’s last show in Iran was in 2021, at the Dastan Gallery in Tehran.

“I didn’t really have a big problem with censorship, but there were some pieces that I knew that I could not show,” she says.

The fight for women’s rights in Iran reached a watershed moment in 2022, as the world reeled from the death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman arrested for allegedly violating the hijab law and who was, according to witnesses, beaten to death while in custody. Scores of Iranian women responded in protest, many by refusing to wear hijabs and others through mass demonstration, bringing new attention to a decades-old plight.

“Power can delete a body, but cannot cut it from its root,” Kashiha told writer Hanno Hauenstein in a conversation for Art Basel. “Physically, that body no longer exists, but the idea and the soul remain and continue in other bodies. The Iranian protest movement has led me to articulate much better why I work with bodies and also to feel a stronger sense of connection to my homeland.”

Kashiha developed a love of visual arts while attending a government-led afterschool arts academy in Tehran. In 2010, a year after completing her undergraduate painting degree at the University of Tehran, she began her graduate studies at BU. Until her time at CFA, she was concerned with technical precision, with perfection.

“This is not my concern now,” she says. “When I was in Iran, some of my teachers told me, ‘You cannot bring these cartoonish things into your work.’ But when I came to the US, I learned a lot of things that changed my work.”

I like to bring the idea to my work of being a fragmented person—which is so feminine. It’s that you cannot define yourself as one person in the way I think a masculine view of the world pushes you to do.

The tension between Kashiha’s old and new styles is distinct in her paintings. Cheeky, caricature-esque squiggles mingle with glossy shapes that look like they’ve been rendered with a computer program. Kashiha honed her technique at several artistic residences, including the MacDowell community in New Hampshire. She headed back to Tehran in 2016.

Kashiha, who has exhibited work on three continents and in seven countries, asserts that the scope of her subject matter is global.

“Within the art history of each country, women are ignored a lot,” she says. “I think there is a fight between feminine and masculine views of the world.”

In her work, Kashiha rearranges and skews women’s bodies with a Cubism-inflected sensibility. The human forms are typically the most representative elements on the canvas; most nonhuman objects are condensed into avant-garde shapes and swashes of color. The effect is that of a collage, a jumbled-up world that can exist in no physical location.

“One reason that I like to bring bright and sharp colors into my work is that they are so beautiful, but they can really bother you,” she says. “I am always working with dual meanings: beautiful and ugly, love and hate.”

Kashiha likes to play with established gender tropes—some sitcom-y and some literary, some abstract and some figurative, some concerning the male gaze and some the female—that take on a more somber context when considering the country in which she’s painting them. Women are shown regarding themselves, as with her Look at the Mirror, or are regarded via a lampooned male gaze, as with The Eye, The Eyehole, The Hole. Much like her personal and artistic refusal to commit to a single geopolitical characterization, Kashiha won’t adhere to a single point of view or dominant narrative. In fact, there’s meaning to be found in the disparity.

“I like to bring the idea to my work of being a fragmented person—which is so feminine,” she says. “It’s that you cannot define yourself as one person in the way I think a masculine view of the world pushes you to do.”

Left: Look at the Mirror (2021) Acrylic on canvas; 59 x 51 in. Right: The Eye, The Eyehole, The Hole (2021) Acrylic and wood glue on canvas; 47 x 39 x 1 in.

Bodies of Work

While Kashiha has made a strong impression on the art world with her bold colors and wry representations of gender conflict, assigning her a signature style or subject matter would be doing her a disservice.

“I usually try to create different bodies of work and each has its own statement,” she says.

Not every Kashiha painting is cartoonish or highly colorful, or features a human body. Brush techniques vary widely—from Expressionism to eerie perfectionism—oftentimes within a single canvas. What Kashiha wants her audience to take away from her eclectic catalog are musings “about power, about narcissism, about bodies that are fragmented, and that are joining together.”

Another theme that unites her works is the practice of seeing. Although she’s often depicted gendered ways of viewing a woman’s body, her most recent narrative series tackles the notion of vision in general.

“I made a body of work that was all about blackness, and I named it In Appreciation of Blinking,” she says. “I made eight canvases; in the first canvas, the eye is open, and then it becomes more and more closed, so that at the eighth canvas the eye is completely closed, and [the canvas] is totally black.”

In Appreciation of Blinking is about a woman who is born in the first canvas—eyes open to a vivid collage of motion, figuration, and color—and dies in the last, where the subject’s eyes finally close for good. Each canvas in between gets a progressively larger wash of black paint to mimic a closing eye. It’s Kashiha’s favorite series, she says. It was also a major change of form for Kashiha, who doesn’t typically gravitate toward multi-canvas series, the concept of life and death, or painting an entire canvas black. But if there’s one thing to remember about Kashiha, it’s that she is constantly coming to new understandings about the world and herself. Deep down—beneath the humor, frustration, and joy—is an enduring question that keeps her returning to the easel.

“I am always asking myself if I am one person or if I am fragmented,” she says. “Are we single bodies that are separated from each other or are all of us in a kind of continuity with each other?”