Images of Motherhood

Toni Pepe finds inspiration and meaning in 20th-century newspaper photography

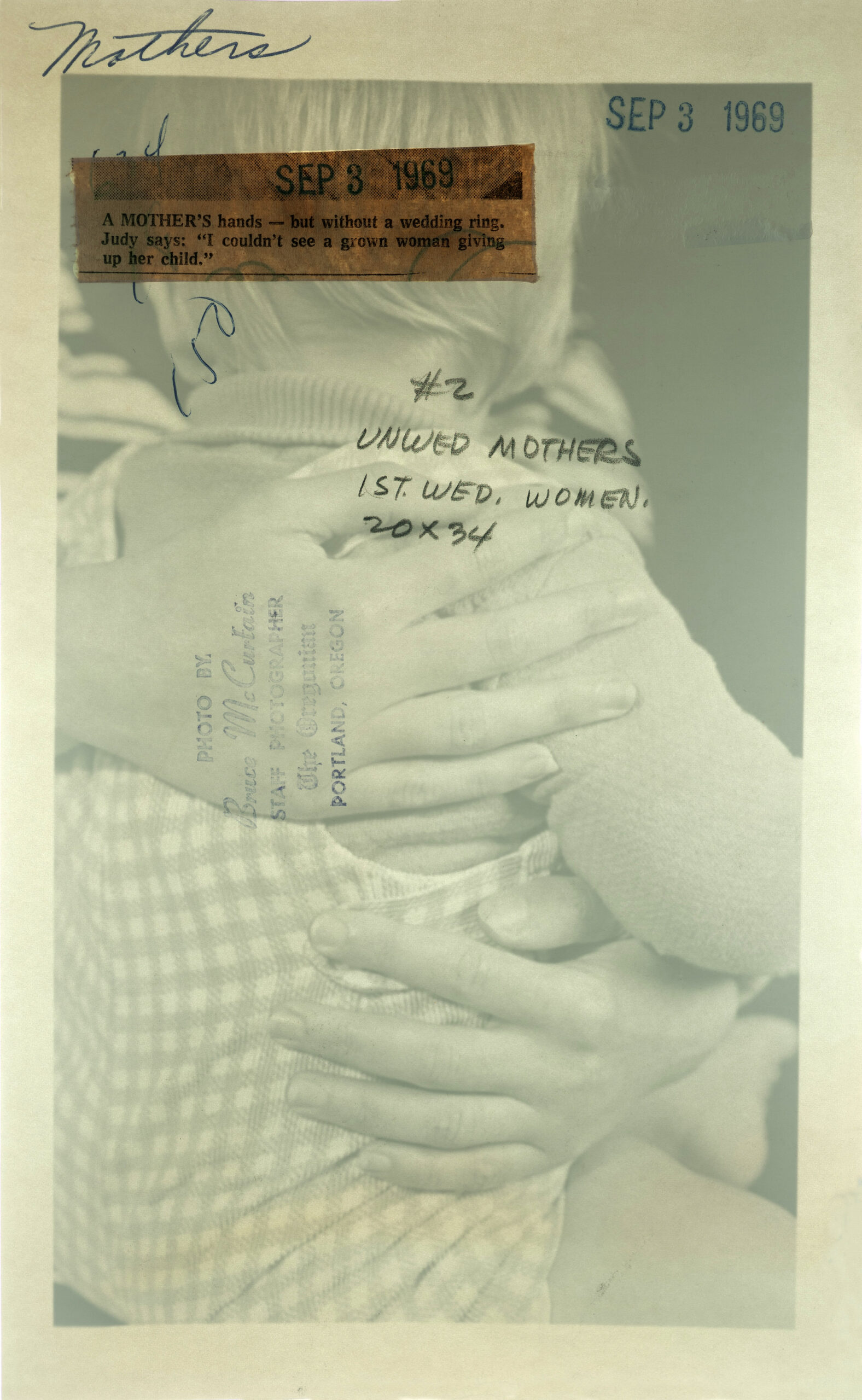

Unwed Mothers (2020) Archival Inkjet; 13 x 16 in. All images courtesy of Toni Pepe

Images of Motherhood

Toni Pepe finds inspiration and meaning in 20th-century newspaper photography

Toni Pepe’s studio is packed with boxes of vintage photographs. She’s collected entire albums from her family. Photos of total strangers come from flea markets, thrift stores, and online purchases. More arrive in the mail every week. Pepe’s photography is often inspired by these old images. She references them when staging self-portraits and incorporates them into mixed-media works of art. “My work has always been loosely related to the family album,” she says.

Becoming a mother in 2012 sharpened her focus. “It just felt natural to explore this new identity that comes with a lot of baggage. It was this marvelous, crazy, magical experience that I felt compelled to somehow unpack,” says Pepe (MET’11), an assistant professor and chair of photography. She began by including her children in her photographs—and she contemplated new projects. One night in 2016, Pepe typed “mother and child” into an eBay search and discovered some old press photos. The images, abandoned when newspapers transitioned to digital archives or went bankrupt, provide glimpses of how mothers were viewed across the 20th century. Pepe began buying photos and thinking of ways to use them. In 2019, she launched an ongoing series: Mothercraft.

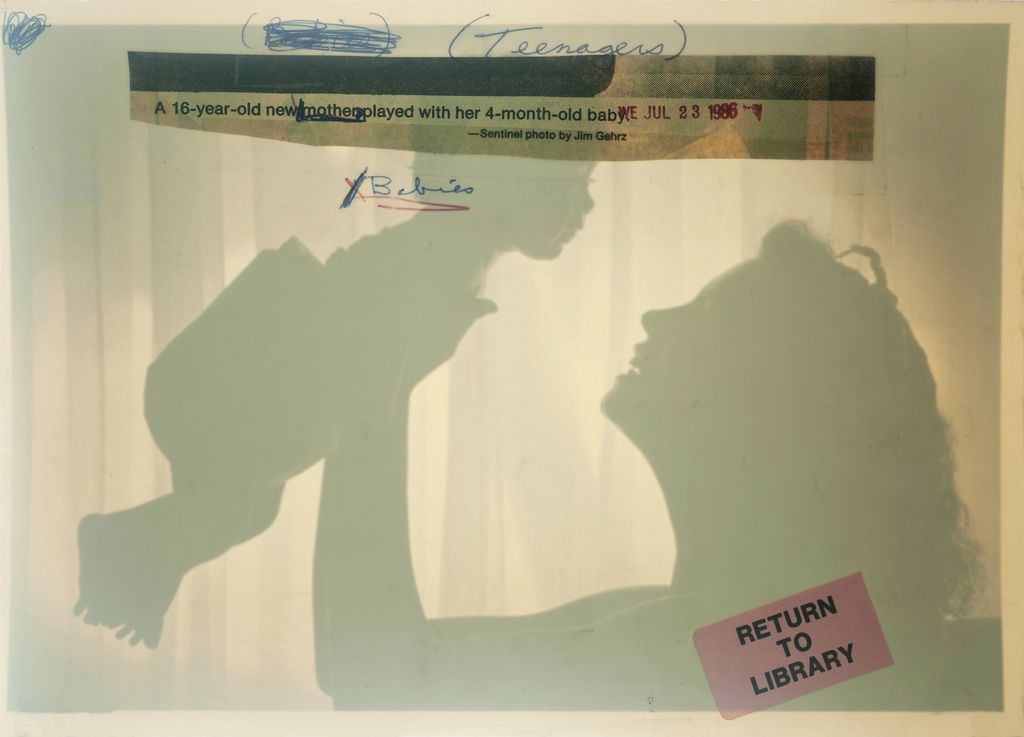

Left: Mothercraft (2020) Archival Inkjet; 28 x 35 in.; Teenagers (2023) Archival Inkjet; 35 x 28 in.

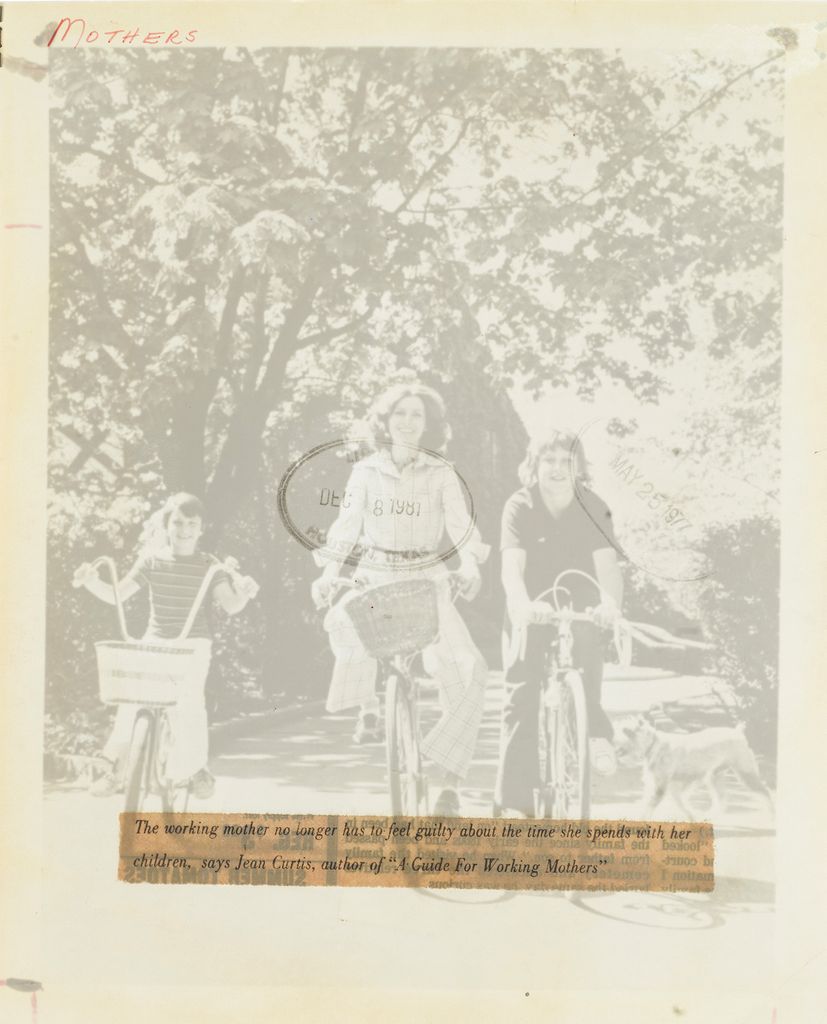

The press photos are distinct because the backs of each print bear the marks of a bygone era of journalism. Cursive pencil script communicates instructions to printers, rubber stamped dates create a timeline of usage, and typed captions explain the subject of each image. “It was really the text that drew me in,” she says. “They are like these little time capsules.” Pepe makes her own photographs of the press photos by hanging them from a wire in her studio, backlit with strobes. The blast of light provides the contrast she needs to capture the image from one side and the text from the other in a single frame.

The name of the project comes from one of the first press photos that Pepe acquired. It’s a yellowed print of a mother comforting her infant. A piece of newsprint, pasted to the back, reveals the text that accompanied the picture in the paper: “For nine months before the baby’s birth, its constant lullaby has been the heartbeat of its mother. This is one reason a baby needs to be held close to its mother. It’s part of ‘mothercraft.’”

Another image in the series shows a bawling baby clutching the side of its crib. The caption reads, “Dennis O’Neal, 6 months, screaming for his mother who is off playing bridge.” Pepe often uses the copywriters’ words to title her pieces, including Mothercraft, Off Playing Bridge, Test Tube Baby, and Illegitimate.

“Sometimes they’re hilarious, and other times they’re incredibly upsetting,” Pepe says of the captions. “I like when the text points toward a time period and the kind of belief and value system of that time.” A 1941 photograph of a baby with its diaper around its feet illustrated a story about the childcare needs of women working during World War II. The child is identified as “A tiny inmate” at an emergency hostel. The caption for a 1969 photo reads, “A mother’s hand—but without a wedding ring.”

“I’m really interested in how photography has shaped what our idea is of a mother and what a mother should look like and how she should behave,” Pepe says. The series now includes more than 100 images, and they reveal many historical stereotypes and tropes. Captions focus on marital status, career decisions, birth control, and gendered parenting roles. “These identities maybe aren’t created by the press photos, but it’s one way in which they were disseminated,” she says.

“I’m really interested in how photography has shaped what our idea is of a mother and what a mother should look like and how she should behave.”

Pepe was also drawn to the physical nature of press photos. They’ve been handled and scribbled upon, stained and creased. “They’re not precious,” she says. “They start as objects in the world, and I want them to end as objects in the world.” To accomplish that, she prints them on thin kozo paper, made from the paper mulberry plant, then pins each print in a frame so it can hang loosely and bend and curl naturally. She prints some in a large format, 35 or even 50 inches wide, and groups others in grids of smaller prints.

More than 30 images from the series are on display at the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, Ore., this year. One piece, Mothers, is part of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, exhibition Tender Loving Care, which runs through July 2025. Pepe has also begun thinking about designing a book.

As Mothercraft has expanded, Pepe’s changing experiences as a mother have shaped the project. “I’m starting to turn toward other kinds of imagery, and thinking more broadly about time and our experience of it,” she says. “That’s one of the reasons I wanted to explore motherhood—because my own experience of time was totally disrupted.” Press photos of the cosmos, calendars, and timepieces have joined the images of moms and babies.

From left: The Time She Spends (2022) Archival Inkjet; 28 x 35 in.; Off Playing Bridge (2020) Archival Inkjet; 28 x 35 in.; Mothers (2020) Archival Inkjet; 28 x 35 in.

Assembling Mothercraft altered Pepe’s understanding of time in another way.

A recurring theme across the series is abortion. “I would read these stories and I felt kind of distant. I was looking to the past and thinking, ‘These poor women—what a terrible time,’” Pepe says. There’s coded language used to describe one woman’s death “under strange circumstances.” Another image, depicting a happy young woman playing on a beach, accompanies a story about the arrest of her doctors on charges of homicide “as a result of an abortion.”

When the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, ruling that abortion is not a constitutional right, Pepe began looking at her project in a very different light. “My relationship to time is different. Time doesn’t necessarily mean moving forward, doesn’t necessarily mean progress.”