Everybody Is a Gamer

Video game veteran Jonathan Knight wants to make the New York Times the premier destination for digital puzzles. Acquiring Wordle was just the start.

Photos by Gabriela Hasbun

Everybody Is a Gamer

Video game veteran Jonathan Knight wants to make the New York Times the premier destination for digital puzzles. Acquiring Wordle was just the start.

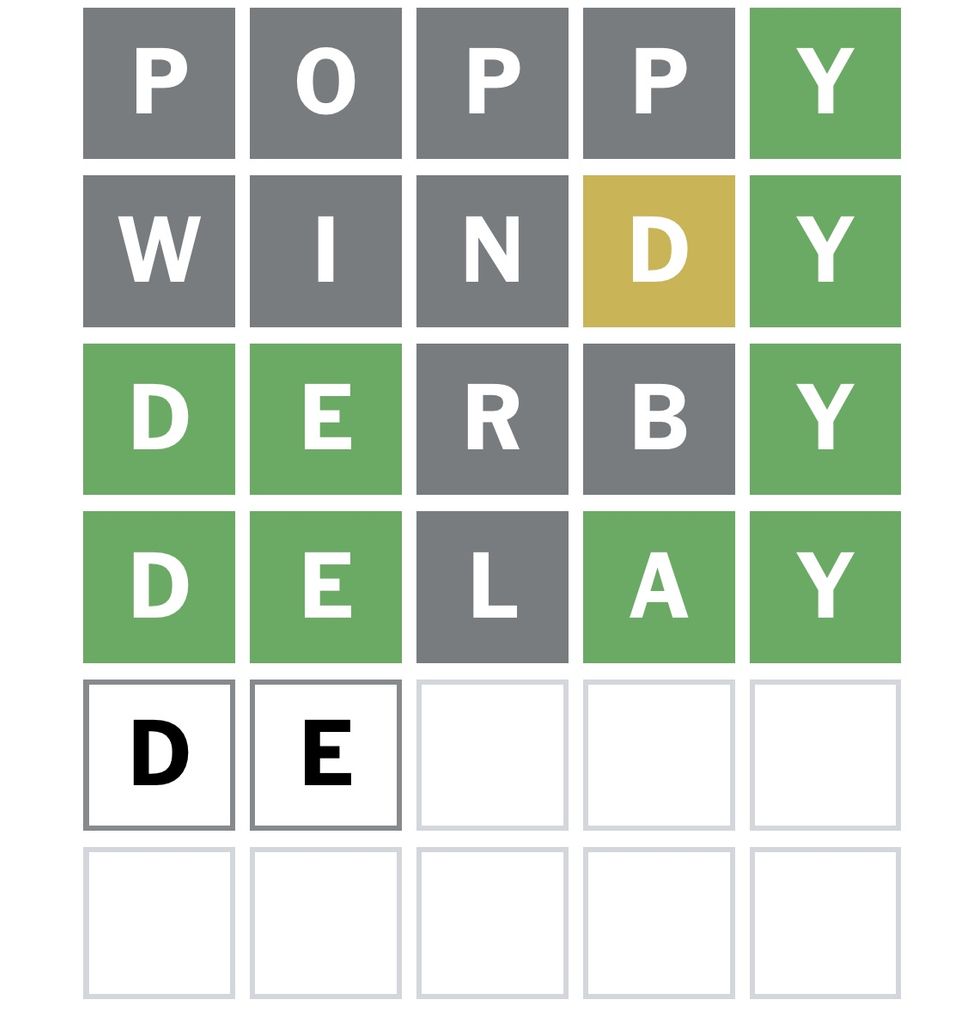

A word-guessing puzzle seems like an unlikely viral sensation, but Wordle was the right game (simple, satisfying, shareable) at the right time (late pandemic doldrums). Players get six attempts to guess a five-letter word. Color-coded tiles reveal which letters they’ve guessed correctly and which they haven’t. Within a few minutes a player can solve the puzzle and share the now-iconic gray, yellow, and green results grid. For many fans, it’s become a daily ritual.

Josh Wardle, the software engineer who designed the game for his partner, released it to the public in October 2021. Within three months, 300,000 people were playing each day. Within four months, Wardle was a millionaire.

Following a January 3, 2022, New York Times story about the phenomenon—“Wordle is a Love Story”—the number of players shot up to 2 million a day. One of the new converts was Jonathan Knight, senior vice president and head of games for the Times. “I woke up the next day, and the first thing I wanted to do was solve the new Wordle,” he says. “It really sticks with you.”

Knight (’94) had joined the Times in 2020 with a mandate to grow the company’s games division. The simplicity of Wordle evoked games the Times was known for, like the classic crossword puzzles and Spelling Bee, which challenges players to form words from a cluster of letters. Knight reached out to Wardle and, on January 31, 2022, the Times announced its acquisition of his game. According to the paper’s own reporting, the price was “in the low seven figures.”

Games have been an important feature of the Times since 1942, when the paper began including a crossword puzzle for entertainment during wartime blackouts. The recent explosion in gaming on smartphones has opened the door for innovations—from improving on old classics to finding the next big thing. The Times launched a crossword app in 2014 (saving puzzlers from the eternal question of pen versus pencil) and has slowly introduced new games since then. Globally, video games now out-earn the film and music industries combined, pulling in almost $250 billion last year. For the Times, games are a revenue source and a gateway for players to find its other products. And to maximize that potential, the company turned to Knight. A veteran of the video game industry, he had worked on titles that helped revolutionize console, mobile, and social gaming. More important, he’s an evangelist for all kinds of games.

“I really believe that everybody is a gamer,” Knight says. “It’s fundamental to human nature—we have a deep need for play.”

Jonathan Knight is senior vice president and head of games at the New York Times, where he’s met his mandate to grow the company’s games division.

Gamer becomes game-maker

Knight had an unorthodox background when he hit the job market in 1994. He had majored in drama and minored in math at Colorado College, where he’d taken the few computer science courses he could find. Then he earned a master’s in directing at the CFA School of Theatre.

Knight also had a lifelong passion for games. He and his brothers had played hours of Risk, Monopoly, and Civilization when they weren’t at the arcade. Their father was such a board game fanatic, he special-ordered games from England before their US release. They moved to video games and learned to write code after the family bought an Apple II computer. Knight even designed a text-based Star Trek game. But, he says, “it was such a hobbyist kind of environment.”

That changed by the time he graduated from BU. The video game industry was maturing, and his combination of skills was appealing. “That was a time when technology and entertainment hadn’t fully intersected, so I had a pretty unusual résumé.” Interplay Productions, a video game company in Irvine, Calif., hired him as a line producer, which involved scheduling, tracking, and some design work.

A video game, it turns out, has a lot in common with a play. “Figuring out how all the different pieces of the video game team need to be motivated and taken care of was, in retrospect, kind of similar to actors and set designers,” Knight says. “The people who make these things need to be organized and directed to get a final product.”

After a year at Interplay, Knight began ascending the ranks at some of the biggest companies in gaming. At Electronic Arts, he directed and executive produced Dante’s Inferno, a game that debuted with a splashy Super Bowl ad, and oversaw its The Sims franchise, then among the best-selling games of all time. As a senior vice president at Zynga, he worked on FarmVille and Words With Friends, games that revolutionized mobile and social media gaming. When the New York Times hired him, Knight was a studio head for WB Games, overseeing development of games in the Harry Potter, DC superhero, and Lord of the Rings universes.

The hobbyist environment that Knight recalled from his childhood is long gone. “A blockbuster video game is the biggest entertainment launch of our time,” he says. “Grand Theft Auto 6 comes out in 2025. It will be bigger than any movie’s opening weekend.”

Games can satisfy a need for validation, competition, or social interaction. Knight saw the power of games to unite people when he worked on Words With Friends, which is similar to Scrabble. Words With Friends took advantage of mobile platforms to allow distant friends and family or total strangers to play together. A few people met their future spouses in the game.

Knight says that when he announced he’d be joining the Times on LinkedIn in 2020, his Silicon Valley friends were surprised. “All of my network was like, ‘The New York Times makes games?’”

“I think Wordle was so awesome at this,” Knight says. “It brought the English-speaking world together at a moment, late in the pandemic, when people were super burned-out and partisan. Suddenly, here was this thing we could all agree on and do together and share with one another.”

Games have even become a form of communication. Just look at the 2022 story of Denyse Holt, Knight says. An avid Wordle player, Holt religiously shared her results with her daughters. Then, one day, she didn’t. Alarmed, they reached out to neighbors and notified the police, who found Holt trapped in a bathroom where an armed intruder had locked her 20 hours earlier.

We’re doing something unique. We offer elegantly designed, clean puzzle games. It’s one a day—you put it down and come back tomorrow. It fits into your life.

The next big thing

Games were expanding at the Times before Knight’s arrival. The crossword app had a devoted following. In 2018, they moved another print game, Spelling Bee, online. According to Vanity Fair, there were 850,000 subscribers paying for full access to the games library by 2020. Still, Knight’s Silicon Valley friends were surprised when he announced his career move on LinkedIn. “All of my network was like, ‘The New York Times makes games?’” he says.

Knight, however, saw great potential: a prestigious brand, dedicated to crafting classic games. Three years into his tenure, the games team has grown to about 100 people. They include puzzle editors, software engineers, designers, product managers, producers, data analysts, and marketers. They’re responsible for a range of daily games, including the Crossword, Mini crossword, Spelling Bee, Wordle, Connections, Sudoku, Letter Boxed, Tiles, and Vertex. Most can be played for free, once a day, but $6 per month unlocks the iconic Crossword and other features, including a 10,000-puzzle archive. Knight’s pitch for upgrading? “It’s the cost of a Starbucks!”

Since buying Wordle, NYT Games traffic has increased by 10 times, Knight says. According to Axios, that translates into 8 billion games played in 2023. Converting even a fraction of those players to subscribers to one of the Times’ products—such as stand-alone subscriptions for news, sports, recipes, and product reviews, in addition to games—is a lucrative prospect at a time when many newspapers are going bankrupt. For Knight, there’s another indication of success: these days, he’s attending Times’ board of directors meetings. “The spotlight is definitely on us,” he says.

Behind the scenes, his team is trying to design the next big thing. They hold an annual hackathon where anyone in the company can pitch ideas. The best ones go through a development and review process and, if they survive that, get beta tested. Then the team uses analytics to see which games are drawing players back again and again. Two 2023 beta tests led to opposite fates. Digits, which challenged players to combine numbers in a series of mathematical equations, was released in April but was discontinued four months later. Connections, which requires players to identify themes in a set of words, was released in June and took off, quickly becoming the Times’ second most played game behind Wordle.

“We’re doing something unique,” Knight says. “We offer elegantly designed, clean puzzle games. It’s one a day—you put it down and come back tomorrow. It fits into your life.” There’s no attempt to encourage binge playing. You can subscribe or play for free, but you won’t be bombarded by in-app purchases or unskippable ads, the bane of many free-to-play mobile games. And, in this age of artificial intelligence, Knight is proud that Times games still have a personal touch: “We’re offering a handcrafted experience. We’re humans making these puzzles every day.”

What’s next for NYT Games? They began a beta test of Strands, a modern take on the word search and launched a redesigned Games app in March. What, exactly, the Games team will unveil next is a closely guarded secret—but Knight trusts their process and promises it will be exciting. “It’s working,” he says. “And I think we’re winning.”

That’s not hyperbole. The booming popularity of Times games prompted a 10-page feature on Knight and his team in the February 2024 Vanity Fair. The video game industry has taken notice as well. Polygon, a Vox Media site that covers gaming, named Connections one of the best games of 2023, on a list dominated by massive, world-building adventure games filled with photo-realistic graphics.

And when Knight goes to the annual Game Developers Conference, he no longer gets blank stares. “Now, everyone’s like, ‘Oh, it’s the Wordle guy! Can I get a selfie?’”