The Proof Is in the Music

Ethnomusicologist Grace Koch has spent her career studying the connection between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music and land rights

In this 1898 image, researcher Charles Myers uses a phonograph to record ceremonial music of the people of the Torres Strait island Mer. Photo by Anthony Wilkin, courtesy of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge [N.23209.ACH2]

The Proof Is in the Music

Ethnomusicologist Grace Koch has spent her career studying the connection between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander music and land rights

In March 1898, researchers from Cambridge University set sail from London for the Torres Strait Islands, an archipelago between Papua New Guinea and the northeast tip of Australia. The leader, anthropologist Alfred Cort Haddon, had visited the area a decade earlier and wanted to learn more about the islanders before exposure to white civilization altered their culture forever.

The expedition, like many of its era, left a complicated legacy. Journals from the trip include racist language. Cultural artifacts taken by the researchers remain in British museums. And yet, their musical recordings (on wax cylinders), photographs, and films have provided a way for today’s Torres Strait Islanders to reconnect with their ancestors—and to help them reassert rights to their land.

“It was probably one of the first expeditions to use multimedia,” says Grace Koch (’73), an ethnomusicologist at Australian National University and a researcher at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS)—and a leading figure in establishing the significance of music in the Aboriginal and islander land rights movement.

Koch has studied musical traditions across Australia. One of the consistent themes is a connection to the land. The recordings from Haddon’s expedition, some of the first ever made by anthropologists, provide a unique look at music that has continued to be passed down to younger generations and which, over the past half century, has helped to establish Torres Strait Islanders’ rights to land that had been taken by the British Crown. Those traditions live on in music across the continent. In parts of central Australia, for example, knowledge of kujika—songs about creator spirits moving across the land—was the Aboriginal way of proving title to a piece of land.

“The people who own the songs own the land,” Koch says.

To the Outback

The course of Koch’s life changed soon after graduating from BU with a master’s in music education. Her husband, Harold, had received a PhD in linguistics from Harvard and accepted a job at the Australian National University. The couple moved to Canberra in 1974 and Koch briefly taught music. In 1975, she joined the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies (now AIATSIS). She worked with Alice Moyle, a pioneer in ethnomusicology, the study of a culture’s music.

At the same time, an Aboriginal rights movement had sparked dramatic legislation. In 1976, the country passed the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act (ALRA), covering an area of more than half a million square miles. The new law allowed Indigenous people to obtain a freehold title to their land after centuries of displacement by settlers—but first they had to prove ownership. That left the challenging question of how a document-based legal system would handle claims from societies that rely on oral traditions. One solution was to study their music.

Koch, new to the country and even newer to ethnomusicology, was poised to play a role in a pivotal moment in Australian history.

The Alfred Cort Haddon 1898 Expedition (Torres Strait and British New Guinea) Cylinder Collection. Koch interviewed the descendants of the people featured in these wax cylinder recordings. © British Library Board

Mapping Native Music

Many Aboriginal songs depict the creation of land, including identifiable features like mountains and water sources. Songs also helped generations pass down information critical to survival, such as the locations of certain plants. In Torres Strait, songs helped sailors navigate around islands and reefs. “Because you can map these songs, it’s hard evidence,” Koch says.

Establishing that evidence was a lengthy process, with anthropologists, linguists, and ethnomusicologists providing a bridge between native and European cultures. Koch would travel to the Northern Territory—often remote areas, some without roads—for weeks at a time. Sometimes that meant picking up people at settlements where they’d been forced to relocate and taking them to their ancestral land. She recorded their songs, listened to their stories, and created genealogies. “It was very exciting—we were out there where hardly any white people had been,” Koch says.

As she traveled around Australia, Koch gained an appreciation for how native music varied between regions. She describes the single melodic lines sung by people in Central Australia—though she also recalls listening to a group of women singing a polyphonic song. Each voice began at a different time and created a cluster of sound. “That was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever heard,” Koch says. “Especially because they were so involved with the story and the site they were looking at.”

The evidence that Koch and her colleagues gathered was provided to the Aboriginal land commissioner who would rule on the claim. The commissioners would often hear songs and ceremonies performed by the people making the claim. Many of those claims were successful, but the Land Rights Act only applied to the Northern Territory in north-central Australia.

In 1992, Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2) brought the issue of native title—a legal recognition that Indigenous people have rights to their land based on their own traditions and customs—national. Eddie Mabo, a native of the Torres Strait island of Mer, had become a prominent advocate for Indigenous land rights and, in his lengthy legal battle, he frequently cited the importance of songs.

Everybody who listened to it was so moved—a lot of people cried. This was very important to their own identity. It gives them a link to their past.

The ruling on the case came from the High Court of Australia, which rejected the idea that there were no legal claims to Australian land before the arrival of British settlers. The Native Title Act was passed in 1993, allowing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to claim title to their lands.

In 2013, Koch published the results of a study of the prevalence of music as evidence in land rights and title claims. She found that 64 of 67 land claims made under the ALRA through 2010 cited music, ceremony, or dance. Songs or ceremonies were performed for the land commissioners in more than half of those hearings. A majority of the 108 title claims made between 1993 and 2010 also included references to song and ceremony. Repeatedly, the commissioners and justices ruling on the claims cited the importance of music in determining ownership of the land.

A Return to Torres Strait

In 2019, after decades of helping Australia’s Indigenous people communicate the importance of their music to Western society, Koch received a unique invitation. Researchers at the British Library, with funding from the Leverhulme Trust, a UK grant-making organization, and the UK government’s Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy, had launched the True Echoes project, an effort to make portions of its sound archive more accessible, and to reconnect with the Oceania communities where the recordings were made. They wanted to interview descendants of the people recorded by Haddon’s 1898 expedition.

Years earlier, Koch’s mentor, Alice Moyle, had worked with the British Library to identify and sort the Haddon recordings. To assist with the delicate process of bringing those recordings back to the Torres Strait Islands, they enlisted Koch. Once again, she was mediating between cultures. She found local scholars, familiar with Torres Strait history and customs, to conduct the interviews.

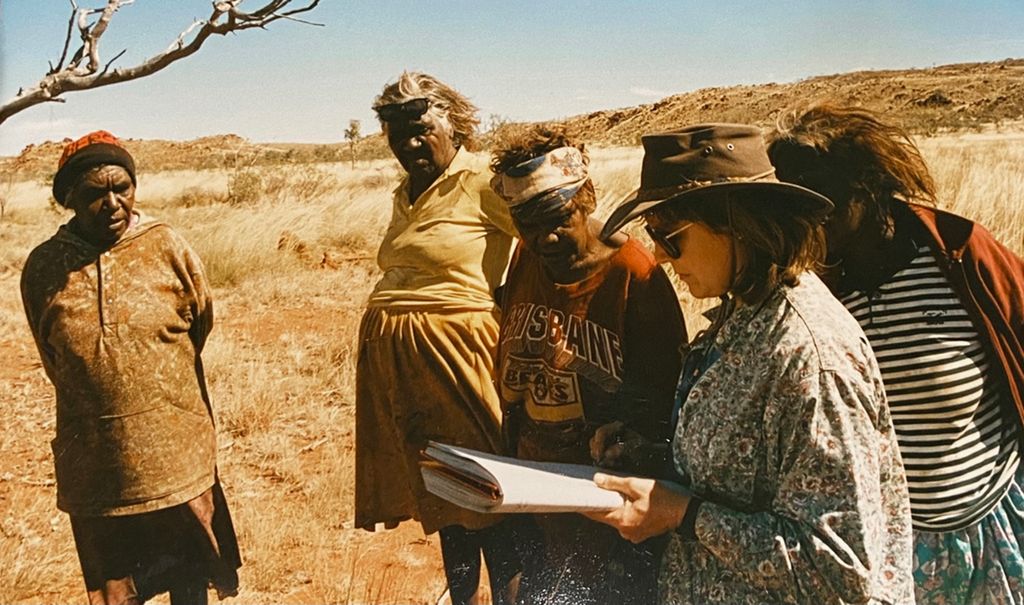

Koch works with claimants for the McLaren Creek land claim in the Northern Territory in 1986. Courtesy of Koch

Participants found the music of their ancestors was still familiar—after all, land remains the theme in their music today. One man sang along to a recording.

“Everybody who listened to it was so moved—a lot of people cried,” Koch says. “This was very important to their own identity. It gives them a link to their past.”

That musical legacy is so powerful, it has reshaped a nation. After nearly 50 years of the Land Rights Act and 30 years of the Native Title Act, First Nations people have rights to approximately half of Australia’s Northern Territory and 85 percent of the coastline.

Those who own the music, own the land.