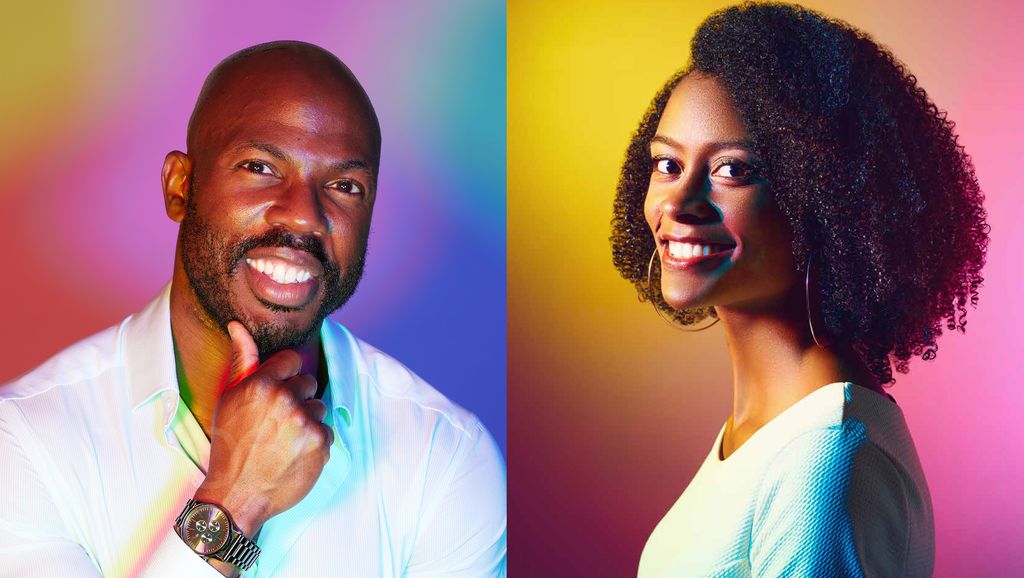

Conversation: Fred Zollo & Harvey Young

CFA Dean Harvey Young and producer Fred Zollo talk about the film Till and the need for more movies about civil rights

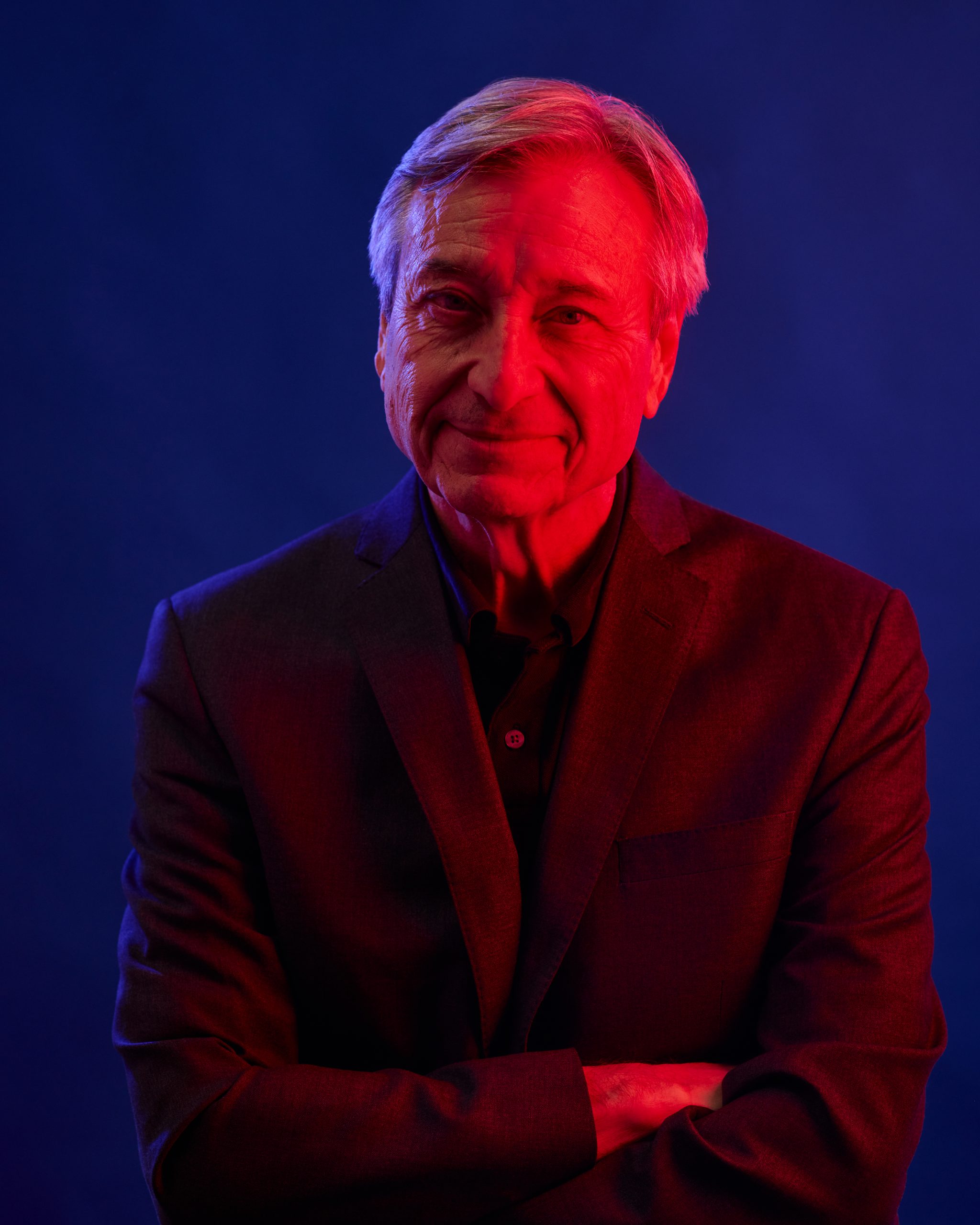

Fred Zollo is one of the most successful Broadway theater producers of all time. He’s been nominated for a Tony more than 20 times and has won the award a dozen times. Doug Levy

Conversation: Fred Zollo

CFA Dean Harvey Young speaks with the producer about the film Till and the need for more movies about civil rights

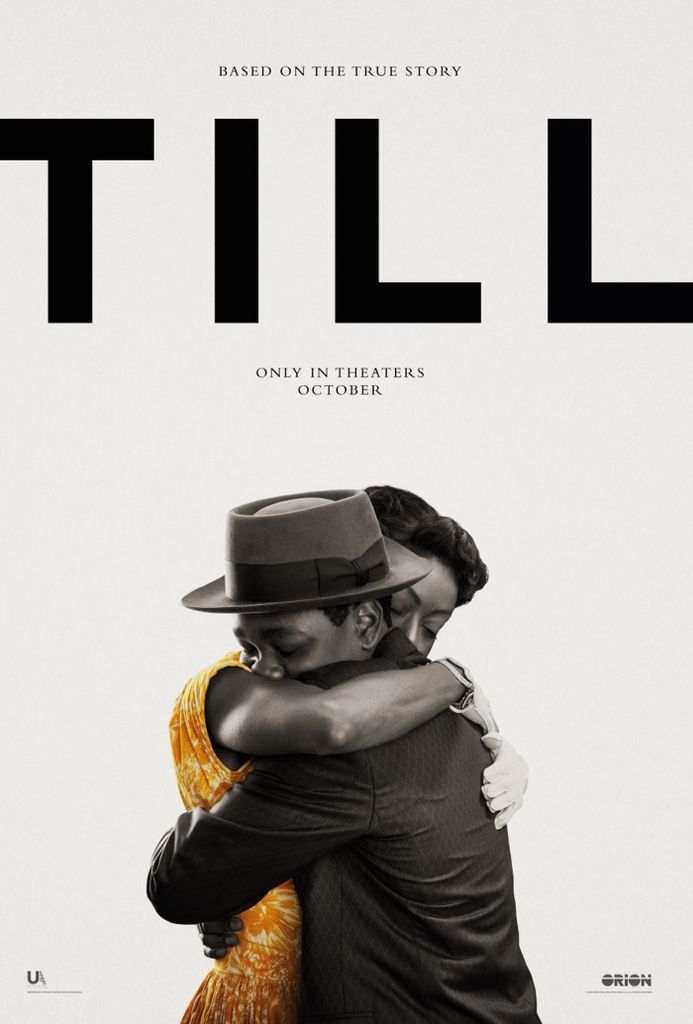

To spend an hour with Fred Zollo is to experience the thrill of talking with a deep thinker. The theater and film producer is gifted with a quick and at times acerbic wit that reveals harsh truths about our society. His perceptiveness and desire to speak out have made him one of our most respected filmmakers. His films include Mississippi Burning (1988), Ghosts of Mississippi (1996), and most recently Till (2022). Till was honored in February 2023 by the Producers Guild of America with the Stanley Kramer Award, which recognizes one film and its producers for using “cinema as a platform to raise awareness for social issues.”

Zollo (CAS’75) is perhaps best known for being one of the most successful Broadway theater producers of all time. But he does not boast about his numerous achievements. In fact, he contends that he doesn’t know how many Tony awards he has won. The answer: he has been nominated more than 20 times and has won the award a dozen times.

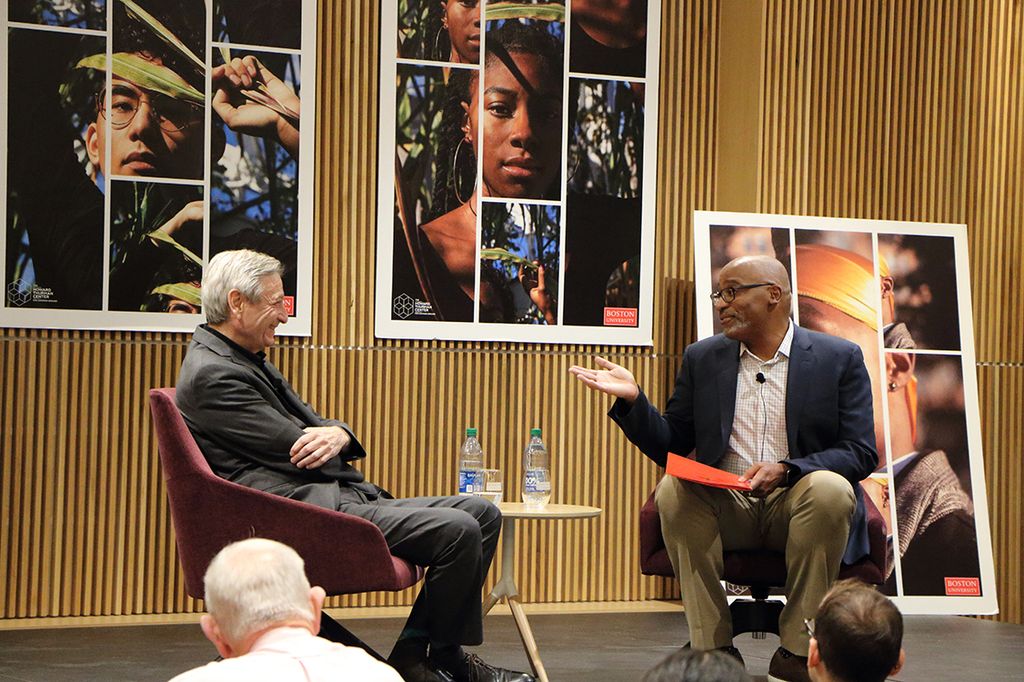

In January, Zollo returned to Boston University—his first visit to the Charles River Campus in nearly 40 years—to speak with me about Till at the Howard Thurman Center. The film tells the stories of Emmett Till, the Black 14-year-old boy who was murdered in a racially motivated attack in 1955, and his mother, Mamie Till Mobley, who bravely displayed her son’s bloated, dead body—and in so doing helped catalyze the civil rights movement. Before a near capacity crowd, Zollo and I talked about the process of making the movie and the urgency of Emmett Till’s legacy in our current Black Lives Matter movement.

Not long after his visit to BU, I called Zollo for a follow-up chat to share with CFA magazine readers. We spoke as he sat in the Hay-Adams Hotel in Washington, D.C., only hours after having been honored by President Joe Biden at the White House, where Till was screened in the East Room in honor of Black History Month. The following, lightly edited for length and clarity, is our conversation.

Harvey Young: Joe Biden hosted you yesterday.

Fred Zollo: He could not have been more kind and supportive. It was great. The last time I was in that [White House] room was when President Obama gave the Medal of Freedom, posthumously, to [Andrew] Goodman, [Michael] Shwerner, and [James] Cheney [civil rights workers who were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in 1964]. Joe Biden was there. We were reminding ourselves of that occasion.

What did President Biden say?

President Biden said it was one of the greatest moments of his presidency to bring Till to the White House. That is quite different than what Woodrow Wilson said at the first White House film screening: Birth of a Nation. He said that D. W. Griffith’s film was “like writing history with lightning.” Lest we forget, Woodrow Wilson was a wretched racist.

Tell me about the process of making Till.

[Director] Keith Beauchamp was only 10 when he saw the Jet magazine photograph of Emmett Till. He committed his life to somehow making the world know about Emmett Till and trying to get some justice for him. Carolyn Bryant, one of the perpetrators [who died in April 2023], pointed her finger at Emmett and set this whole series of terrifying events in motion. No one [was] willing to prosecute her, despite Keith recently discovering a 1955 warrant for her arrest in a DeSoto County courthouse. It was never served. There is a legal question: Is there a statute of limitations on a warrant? There is no statute of limitations on murder.

I met Keith around 2005. I said, “Let’s make a movie of this.” It was very difficult to get people to agree with us and help us make the movie.

Why was it so difficult?

It’s about civil rights. People don’t want to see movies about civil rights. They’re more interested in seeing slave movies. There’s an evil message here somewhere. White audiences will go to see slave movies but not civil rights movies.

It took over 18 years. Barbara [Broccoli, coproducer] was extremely helpful. She brought along MGM and now Amazon. They do the James Bond films. Simultaneously, MGM revived a company that I had a long relationship with, Orion Pictures. That’s where we made Mississippi Burning. It was a reunion of sorts. Orion is [now] run by a brilliant young woman named Alana Mayo. Rare in Hollywood: a woman of color who runs a major movie studio.

You were at this year’s Producers Guild of America Awards.

Till got the Stanley Kramer Award. It is a very high tribute. Stanley Kramer meant a lot to me as a kid. He made a lot of movies: Inherit the Wind, The Defiant Ones, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. He was a remarkable guy. We’ve had a little problem with some of the awards. Apparently, they don’t want to give awards to this subject matter, and they don’t want to honor Black film artists anymore.

And that is shocking. Last fall, there was such buzz. More recently, there’s been a pushback against recognizing Black artists.

They tried to find excuses at first—“We don’t want to see Black people tortured on-screen.” There isn’t anybody tortured in the movie. It is a difficult subject matter. When you put all the excuses aside, it is an all-white Academy [of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences]. The notion that they changed anything is ridiculous. They haven’t. It’s at best sugarcoating without the sugar. It’s still all old, white men, like me.

Civil rights movies—there aren’t many of them. I have now made three of them [including Ghosts of Mississippi].

People don’t want to see movies about civil rights. They’re more interested in seeing slave movies. There’s an evil message here somewhere. White audiences will go to see slave movies but not civil rights movies.

It’s amazing to think about the mainstream circulation of slave movies versus civil rights movies. Not only do slave movies outnumber civil rights movies, but they also gain more audiences and, often, more awards. You will recognize someone for being a slave before you would recognize someone for being a leader of civil rights.

I was talking the other day about a Quentin Tarantino movie that ends with horrific violence against women. No one has a problem with that in Hollywood. They love it. The abuse of women is what Hollywood is all about. Racism and the abuse of women. No matter what the academy says they’re doing, they’re not.

Why do you keep making films when there is such resistance?

I don’t know. All the effort that went into making this film—it is very special. We have this brilliant Black female director, Chinonye Chukwu. There were two Black female directors who did amazing work this year. Viola Davis’ film, The Woman King, is a terrific movie. The director of that film is Gina Prince-Blythewood, who is also brilliant. None of the best director Oscar nominees were women. In a year with Sarah Polley [who wrote and directed Women Talking], Prince-Blythewood, and Chukwu, how was not one woman nominated? And no one in the media cares. Where was the front-page New York Times article?

In looking at the coverage, it’s almost like there is an effort to excuse the absence by noting that women directors won the Oscar in the past two years—which itself was an anomaly in the history of the awards. It does not make any sense.

It does make a lot of sense. The same people are running the show. No matter what they say, they have made no effort at the academy. That’s my opinion.

My dear friend Whoopi Goldberg is on the Board of Governors of the academy. I’ve been hoping that she can convince them to do something different and not do something that obviously isn’t working. You have a situation where a wonderful actress who is not well-known in America—Andrea Riseborough—somehow gets a nomination [thanks to a social media campaign] on a film that has grossed $23,000. Good for her. But it had nothing to do with the normal way that that [nominations] happens. It proves that you can put the fix in if you know the right people. Welcome to America, right?

What are some of your upcoming projects?

We were about to open Sing Street on Broadway—the marquee was up and we were moving into the theater—when the pandemic hit. It opened in Boston in 2022 at the Huntington, and it’ll be coming soon [on Broadway]. There’s a play with Mark Rylance that we’re going to do. It’s a wonderful play that Barbara and I did about 15 years ago, called Frozen. Not to be confused with the Disney musical.

That would really surprise kids [laughs].

It’s a really moving play. Mark Rylance would be extraordinary in it.

Things sort of come around. I’m finally going to do a play by Richard Nelson that I’ve been trying to do. I was going to do it with Mike Nichols 45 years ago, but that didn’t quite happen. Robin Williams was going to be in it.

You were recently back on campus. What still resonates with you?

I was very impressed. I am very happy to see the construction, the cool new buildings, including the Booth Theatre, which is incredible. But it was more the feeling. There is a feeling of excitement there. There is an old television show called Room 222, about a high school in Los Angeles. It opens with a famous theme song as students go into the school. They like the school. The principal is a great guy; he’s trying to do good things. The energy of the students as they are walking into the school in the opening credits—I was thinking about it as I was walking down Comm Ave with you. There is an energy of excitement or “we’re really happy to be here.” That’s the great legacy of Dr. Brown and you. You brought this electricity there. I was very excited by it.

This Series

Also in

Conversation

-

June 3, 2024

Conversation: Gail Shalan and Erin Ruth Walker

-

December 19, 2023

Conversation: Martin Sherman & Kirsten Greenidge

-

June 17, 2022

Conversation: Emily Deschanel and Daria Polatin