Super Animator

Jeff Wamester brings your favorite comic characters to life onscreen

Jeff Wamester is a director at Warner Bros. Animation, where he oversees direct-to-video films based on DC Comics characters. Photo by Patrick Strattner

Super Animator

Jeff Wamester brings your favorite comic characters to life onscreen

When Jeff Wamester was growing up in the 1970s and ’80s in a small Connecticut town, his world revolved around drawing, cartoons, and comics. He looked forward to Saturday mornings, when he could plant himself in front of the television and watch his favorite animated series for hours. “I was absolutely fascinated with shows like Voltron and Macross, which were part of the beginning of anime gaining popularity in the United States,” he says. “I couldn’t get enough of them.” After his morning cartoons, he’d slip away to sketch or pore over a stack of comics. “I read everything from Marvel and DC Comics. I’d borrow them from my local barbershop of all places. They had a bunch of comics that had just been sitting there for an eternity. Some of them were 30 or 40 years old.”

By the time Wamester (’94) was nearing high school graduation, he realized that reading comics and watching cartoons could be more than just hobbies—he wanted to make them for a living. He studied art and illustration at BU and the University of Connecticut and today works for Warner Bros. Animation. As a director, Wamester oversees direct-to-video films based on DC Comics characters, including Justice Society: World War II (2021), which features the Flash, Wonder Woman, Superman, and Hawkman; and Legion of Super-Heroes (2023), in which Supergirl attends a superhero training school.

“Working on these projects is exciting,” Wamester says. “One of the things I find the most fun is trying to dig deep into these characters and consider how they are going to react to certain situations, and how they are going to grow. Every scene means something toward that.”

Building a Film

Wamester’s filmmaking process starts when he gets a script from the writers. It’s his job to make the visuals that bring those words to life. First, he oversees the creation of a storyboard, or a series of drawings that roughly illustrate key moments in the script. He works with a group of storyboard artists, sometimes 10 or more, going over the aim of the film and assigning each one a section of the script to illustrate using the software Storyboard Pro.

“Making storyboards can be a real grind because it’s a lot of drawings you have to do,” he says. “We’re talking probably around 1,000 to 1,200 individual panels that need to be drawn.” Wamester speaks from experience. He got his start in the industry as a storyboard revisionist for the animation company Film Roman’s TV series Ultimate Spider-Man, and continues to work on storyboards on a freelance basis. Revisionists step in after directors request changes to storyboards. They’ll change frames to better fit the timing of the film or television show, add elements to a scene (or take them out), and clean up the drawings to get them ready for the next step: creating the animated version of the storyboard, called the animatic, which plays the rough drawings in sequence, timed to voiceovers and sometimes music.

Wamester has been obsessed with comics and animation since he was a child growing up in a small town in Connecticut. He would borrow stacks of old comics from his local barbershop. “They had a bunch of comics that had just been sitting there for an eternity. Some of them were 30 or 40 years old.” Photo by Patrick Strattner

The foundational skills Wamester developed in classes at CFA, including understanding color theory and rendering three-dimensional objects, have helped him in his animation career. “All of the drawing classes that I took, too, made a huge difference,” he says. “I found that because I had a lot of life drawing experience, I am able to draw really quickly, really accurately, and proportionally. I spend less time thinking about how I’m going to draw something and more time thinking about the story and the points that we’re trying to make. If you haven’t honed your drawing skill like that, then you’re fighting between telling the story and trying to draw the picture.”

There are different approaches to creating storyboards, but the process always starts with a series of more rudimentarily sketched-out versions—the “roughs”—and ends with a set of more polished panels called “cleans.” It can take about eight weeks to storyboard just 7 to 10 minutes of film.

For each film he directs, Wamester oversees the creation of a storyboard, a series of drawings that illustrate key moments in the script. It can consist of more than 1,000 individual panels, like those above from Legion of Super-Heroes. Images courtesy of Jeff Wamester

“Some people pick out key points,” Wamester says, “and they board those first and then go back and connect them. Some people do it more straightforward. I’ve taken that approach. I read the whole story, so I know it in my head, and I’ll start drawing it out chronologically. If I see something’s not working, I’ll backtrack and fix it until it’s got the functional trail or sequence that I want to create in the setup for that moment.” The first draft, he says, is usually just for placing characters and seeing how they are moving through a scene. In later versions, the drawings get more detailed and characters begin to look truer to their final form, with their emotions and expressions added.

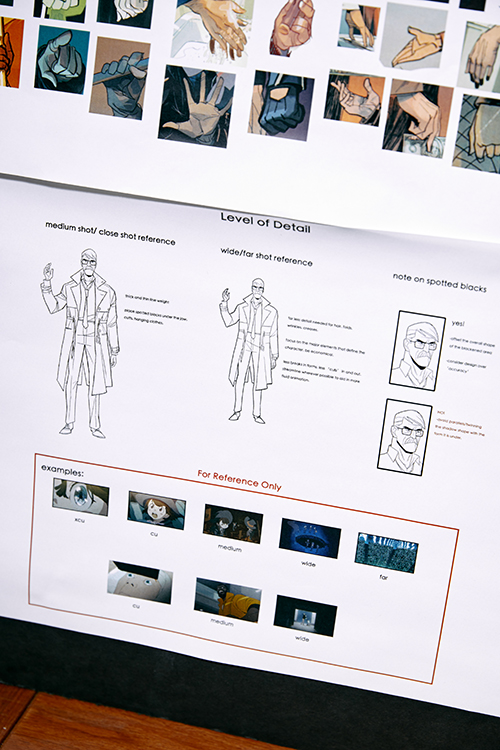

In his role at Warner Bros. Animation, Wamester is also involved in character development and design. Photos by Patrick Strattner

On the films he directs, Wamester gives feedback to storyboard artists as soon as they turn in the first rough panels. “I start making suggestions, like, we need to emphasize this, or this action doesn’t hit the target for what we’re trying to do in this scene, or we can use a better moment here or a different kind of shot.” He’ll get a revised version back to further fine-tune. “Sometimes there will be a story point that I’m like, ‘Oh, this isn’t going to work, whatever way we do it.’ My job is to go to the producer and let them know that I think there’s a problem. Sometimes I’ll even come up with a solution and provide it, writing half a page of the story, or revising lines, adding lines, or pulling lines.”

After the animatic is created, the film heads to production. Using various software programs, members of the animation team refine the pacing and design—including how the characters and environments should look—and animate the sequences, honing the color and lighting, adding voiceovers and music, and working with sound designers to perfect other sonic effects.

All of the drawing classes that I took [at CFA] made a huge difference. I found that because I had a lot of life drawing experience, I am able to draw really quickly, really accurately, and proportionally.

As director, Wamester is also involved in aspects of character development and design throughout the process of making a film. “I go through the script and ask, ‘What is this character’s story, and how do they progress through the story?’” He makes sure that the films stay true to the characters involved. “A lot of the characters we work with at WB exist within this canon. So, when we have a story, we’re thinking about how the canon plays into the story. We’re working within this huge network of stories and interactions, and we’re trying to make sure that what we’re doing is progressing these stories and characters, and motivating them. We want to avoid having a character do something ‘just because.’”

Comic-Con Moment

Wamester will never forget the joy he felt as a kid, reading the comics he borrowed from his barber. “I think ever since I picked a comic up, I’ve wanted to create one myself,” he says. For years, he’d come up with ideas, eventually landing on one he thought was worth pursuing—Electropunk: Children of the Future, an alternative history graphic novel inspired by inventor and engineer Nikola Tesla, who is well known for pioneering the use of AC electricity and who experimented with the wireless transmission of electricity. “Tesla’s lab burned down in the 1890s, and he had said that he had hundreds of experiments in there that were destroyed, a ton of ideas that he was going to follow through on,” Wamester says. “This story kicks in as if that never happened, and through those experiments he discovers there are indeed things that go bump in the night. And so he enlists his orphaned niece and nephew, who he trains from when they’re very young, to help him stop these monsters.”

He pitched the idea to his writer friend B. Dave Walters, who he was hoping would collaborate with him on the graphic novel. “He thought it was such a cool idea,” Wamester says. “We had an initial meeting, and he just took off and wrote the graphic novel, along with a 12-issue miniseries and another origin prequel novel.” In 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, they launched a Kickstarter campaign with the hope of raising enough money to produce the comic. They raised a little more than $45,000, more than their $30,000 goal. After beginning production on it two years ago, Wamester says, they completed a final proof in December 2022 and are looking for a publisher.

In the meantime, Wamester is basking in the full-circle trajectory of his career. In July 2022, he was a panelist at San Diego Comic-Con, where he premiered Green Lantern: Beware My Power, another film he directed for Warner Bros. Animation. He joined the film’s voice actors—Aldis Hodge (Black Adam), Jimmi Simpson (Westworld), and Jamie Gray Hyder (Law & Order: SVU)—onstage to answer fans’ questions about the film. “It’s exciting to have a movie showing up on the screen and have that many people cheer and laugh at places that I had been thinking, ‘Oh, I want to make them laugh here,’” he says.

“It’s hard to explain the level of excitement of people at Comic-Con, and when you get to be onstage, that energy absolutely flows your way. It very much fuels you. I mean, this is stuff that I got excited about when I was a kid, and it’s so cool to be on this end of it now.”