Majority of US Mayors Worried about the Racial Wealth Gap in Their Cities

In an effort to address the racial wealth gap, the city of Stockton, Calif., has piloted a universal basic income program, providing a group of low-income residents $500 per month for two years. Photo by iStock/DenisTangneyJr

Majority of US Mayors Worried about the Racial Wealth Gap in Their Cities

Latest Initiative on Cities Menino Survey of Mayors: city leaders support targeted actions helping people of color own businesses and homes

- 67 percent of US mayors are concerned about the racial wealth gap in their cities, though Democrats’ and Republicans’ views differ.

- Of those mayors worried about a racial wealth gap in their communities, most support targeted programs supporting Black and Latino constituents to own businesses and homes.

- 81 percent of mayors believe that limits on access to capital hurt small business owners of color, and support using technical assistance to help these business owners get loans.

A strong majority of US mayors (67 percent) say they are worried about the racial wealth gap in their communities, with elected leaders in cities with larger populations and higher costs of living significantly more concerned about the issue.

Those mayors who identify the racial wealth gap as a problem for their cities are close to unanimous in their support for programs designed to benefit small business ownership and homeownership for people of color. But when asked about specific programs targeting these problems, most said they would not back them in their own communities.

These are among the top findings in a report issued March 23 by Boston University’s Initiative on Cities (IoC), titled “Closing the Racial Wealth Gap,” which asked elected city leaders about their views on racial inequality in their communities and how cities should address the issue.

The report, coauthored by Katherine Levine Einstein, David M. Glick, and Maxwell Palmer, all College of Arts & Sciences associate professors of political science, is the third in a three-part series of survey results from the 2021 Menino Survey of Mayors.

For the survey, IoC staff interviewed 126 mayors of cities across the United States with more than 75,000 residents. The first report, released in December, examined mayors’ concerns about the mental health of residents coping with the COVID-19 pandemic and cities’ plans for spending federal aid. The second report, published in January, highlighted mayors’ views on homelessness as a crisis they are held responsible for, but said they lack influence to address.

The IoC received support for this research from Citi and the Rockefeller Foundation.

The report’s authors note that American cities “are home to profound racial inequality” that persists across housing, businesses, and retirement assets, especially when comparing the resources available to Black and white residents. In Washington, D.C., for example, white households had a net worth that was 81 times greater than that of Black households in 2014. That same year in the Boston metropolitan area, US-born Blacks had a median wealth amounting to $8 compared to $256,500 for whites.

While two-thirds of mayors in the survey said they are concerned about these trends, the 2021 Menino Survey of Mayors found significant differences in views depending on the type of city and the political party of the mayor. Leaders of cities with larger populations (more than 117,000 residents) and less expensive housing costs (median housing prices below $245,150) were more concerned. While 58 percent of mayors of larger cities expressed concerns about racial wealth disparities, only 26 percent of mayors leading smaller cities said they shared these concerns.

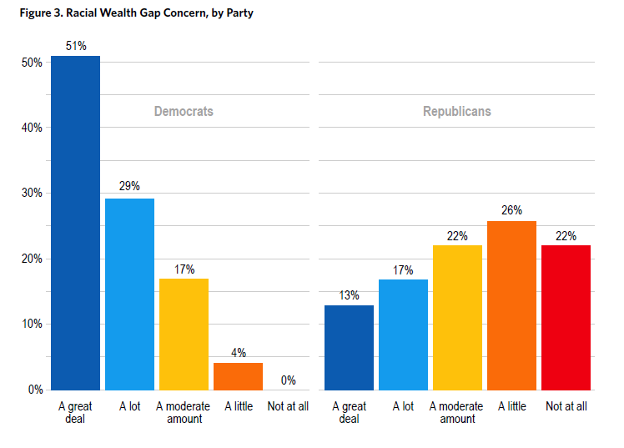

Partisan differences were stark: 80 percent of Democratic mayors expressed concerns about the racial wealth gap in their cities, compared to 30 percent of Republican mayors.

Among those mayors expressing concerns about the racial wealth gap, most said they supported implementing programs to address the problem, including programs to improve access to capital for Black and Latino small business owners, and to increase Black and Latino small business ownership in general. This subset of mayors also voiced strong support for programs to expand Black and Latino homeownership.

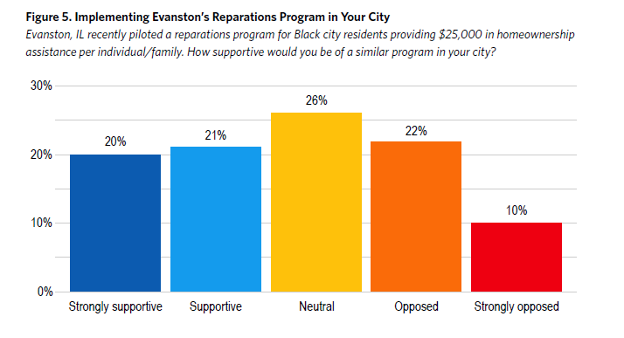

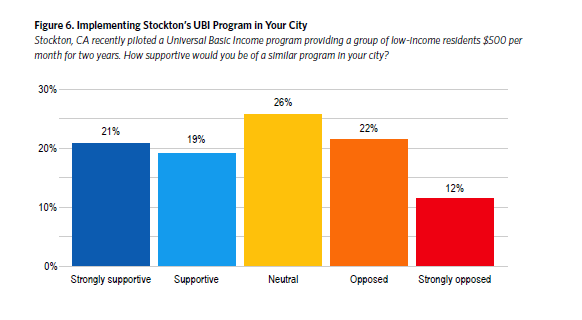

But when it came to specific programs that some cities are trying today, mayors in the survey were less supportive. For example, only 41 percent of mayors who are concerned about the racial wealth gap support implementing a program to provide $25,000 in homeownership assistance to Black city residents, like Evanston, Ill., has done. And only 40 percent said they backed a universal basic income program like the pilot in Stockton, Calif., to provide a $500 monthly payment to a group of low-income residents for two years.

Glick says that researchers, who conducted interviews during summer 2021, were interested in exploring mayors’ views on racial wealth disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic, given the rising pressures on small businesses and the racial inequities in healthcare outcomes that people of color experienced. Given the timing of the research, it was not surprising that most expressed concerns. What was notable, and could require more research, the authors say, is why many were cautious in their support of specific remedies that target recipients by race.

“In general, I think once you start talking about racially targeted policies, some people get uneasy,” Glick says. “There’s clearly something interesting going on there. We don’t have an answer to it, whether it’s that mayors are interested in some [policies] but just haven’t found the right ones, or they are just lacking information or ideas for these types of programs. Whether it is a case of things looking good in the abstract, but the specifics are more challenging—either politically or policy-wise—or some combination of those things.”

In a statement that accompanied the release of the report, Quinton Lucas, Democratic mayor of Kansas City, Mo., says that local governments can make an important difference to the racial wealth gap by making investments.

“Breaking cycles of poverty and building wealth in our communities of color strengthens our economies and builds healthier neighborhoods,” Lucas says. “Local government’s role is about investing in people and places which have for too long not seen the level of investment they need or deserve. We can and must take measures that make it easier for our Black and brown residents to own homes and businesses and to access quality education and good-paying jobs. Local leaders are committed to working intentionally and collectively to address our country’s long-standing racial and economic disparities.”

Mayors taking part in the survey showed consensus when it came to assessing the challenges facing small business owners of color and the need to address the problem: 81 percent believe that access to capital disproportionately harms these small business owners, due to factors such as lack of personal assets, weak networks of friends and family to provide monetary help, a lack of technical help, and lenders’ racial bias.

Mayors also expressed support for a range of ways to help. Close to half (48 percent) of mayors support providing technical assistance or mentoring to address racial gaps between businesses. Nearly a third (31 percent) said city purchasing policies could do more to benefit small business owners of color. And 26 percent of mayors said they would support providing modest amounts of direct financial assistance (less than $20,000).

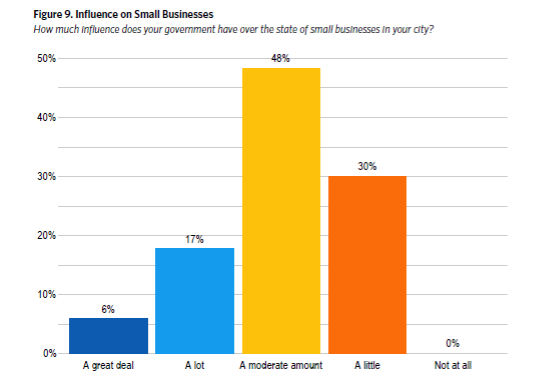

Interestingly, only 23 percent of mayors surveyed said they felt they had a great deal or a lot of influence over the small business environment in their cities, and only 16 percent said they felt they could influence racial gaps between businesses. Glick says that this sentiment—from a group of local elected leaders who like to assert themselves as being able to “get things done” at a local level—could reflect the sense that mayors don’t feel like they have as much power to change large, long-standing societal inequities on the local level.

Palmer says the confidential survey sheds light on mayors’ candid opinions that otherwise would be difficult to study.

“We’re asking mayors hard questions and questions they might not want to answer in public. That is one of the values of the Menino Survey. We never disclose who participates or their answers. And that really gives them the freedom to answer more honestly and to provide views that they might not provide to a journalist or in a public meeting,” Palmer says.

As part of their inquiry into mayors’ views on the racial wealth gap, researchers asked mayors about their views on housing developments and gentrification and their potential impacts on minority residents.

A majority of mayors said they support increasing density in popular established neighborhoods, though Democratic mayors were more likely to support this move than Republicans. A majority also said they see building new market-rate housing as a way of reducing overall housing costs.

Most mayors see gentrification as an issue of displacing existing residents with new ones. In survey responses, 65 percent of mayors used the term “displacement” when asked to define gentrification.

“A pretty big majority all mentioned displacement, with many of them explicitly tying that into race and displacement of communities of color,” says Palmer. “They also tended to describe it as a very active process. They often talked about somebody—whether it’s developers or groups of people—coming in and gentrifying, rather than gentrification as an outcome or something that happens as an area improves. That’s really interesting and plays an important role in how we think about gentrification and dealing with this dual problem of how do you improve neighborhoods without displacing communities, when often the very act of trying to improve something might just be seen as gentrification itself?”

In addition to their views on the racial wealth gap in their communities, mayors perceived discrimination in their cities differently depending on their party affiliation. At least half of Democratic mayors perceived that Blacks, the homeless, Latinos, transgender, Muslims, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Indigenous and Native American people face discrimination in their cities. Republican mayors saw less discrimination of these and other groups. A small percentage of Republican mayors also perceived discrimination against white people in their cities.

Glick says the partisan differences among mayors reflects national trends. “It’s clear that there are some of those same partisan gaps that we see nationally filtering down to the city level,” he says.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.