For BU’s Deborah D. Douglas, Leading The Emancipator Is Part of Her Life’s Mission

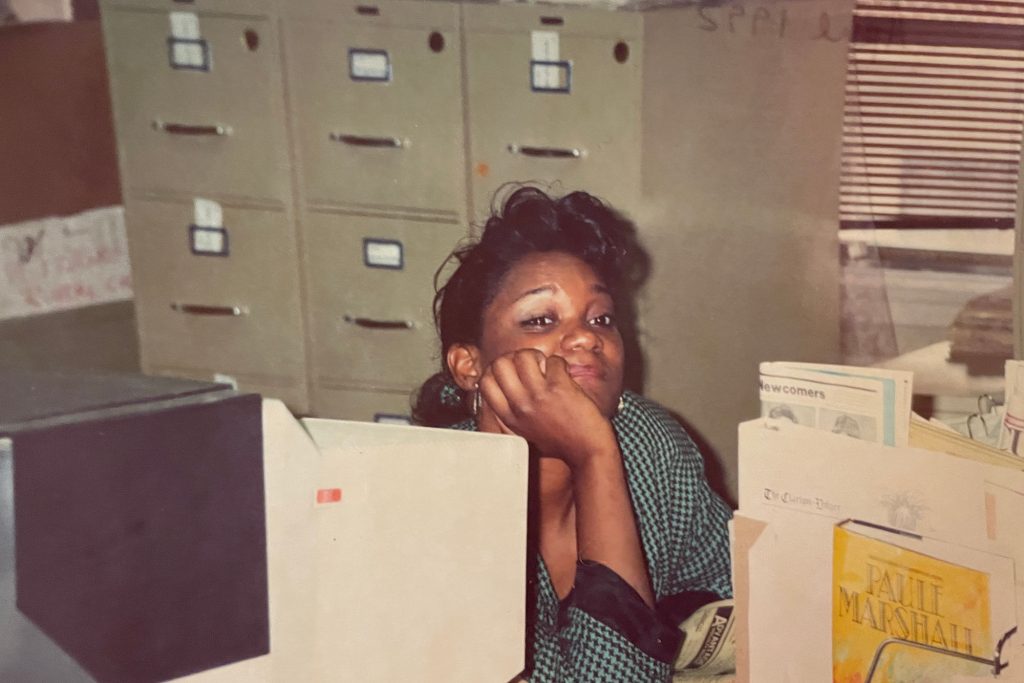

Award-winning journalist Deborah D. Douglas is coeditor of The Emancipator and part of BU’s Center for Antiracist Research. Photo by Ciara Crocker

For BU’s Deborah D. Douglas, Leading The Emancipator Is Part of Her Life’s Mission

Center for Antiracist Research staff member and her Boston Globe–based coeditor, Amber Payne, aim to reframe the conversation around race and help hasten racial justice

Deborah D. Douglas still shakes her head at something one of her journalism professors viewed as news every reader would, and should, care about. “He said, ‘Today there’s something going on in the country that’s really important,” she recalls. “He said, ‘Do you know what I’m talking about? It’s really big.’ And for the life of me, I couldn’t figure out what he was talking about. What was that story he said everyone knew about? ‘It’s Opening Day for the baseball season!’”

“I’m thinking, that’s important to you, white man.” But she kept quiet. “I actually felt shame that I didn’t know it was opening day,” Douglas says. For years she wondered if there was something wrong with her and the way she’d been exposed to culture and life experiences. Until she realized it wasn’t about her. “I’m raised by a series of Black women… They’re not focusing on Opening Day.”

Now, three decades later, Douglas, and another veteran Black journalist, Amber Payne, are the editors in chief of a developing new online platform, The Emancipator. A collaboration between Boston University’s Center for Antiracist Research and the Boston Globe Opinion team, the site will aim to reframe the national conversation around race and hasten racial justice through evidence-based ideas and opinion essays, videos, and annotations of historic documents, poetry and speeches produced by, and with, experts from academia, journalists, and community members.

Douglas, who arrived at BU in July 2021 from DePauw University, where she was the Eugene S. Pulliam Distinguished Visiting Professor of Journalism, works out of the Center for Antiracist Research, and Payne, a former NBC News producer and editor of Teen Vogue, is on the Globe staff. They are laying the groundwork to launch The Emancipator’s website in mid 2022; a weekly online newsletter with original commentary and analyses will begin in January, with simultaneous publication in the Globe’s “Ideas” section and other national outlets. Access to The Emancipator will be free.

The idea for The Emancipator was born amid the nationwide reckoning over race that followed the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and as the pandemic was underscoring persistent racial, economic, and health inequalities. The conversation about race and racism intensified almost overnight, not only in city streets and corporate boardrooms, but also in America’s newsrooms, including the Globe’s, where the editorial page editor and owners wanted to draw on scholarship to reshape the often-ideological debates about racial justice playing out in the opinion news media. Scholar Ibram X. Kendi became an important voice in that conversation, launching BU’s Center for Antiracist Research in July, 2020.

As envisioned by Douglas and Payne, The Emancipator is both a throwback to the 19th-century abolitionist papers that sought to end American slavery and an experiment in journalism’s future. “Our vision is to convene a solutions-oriented community space for analysis, data, and resources as we explore the path toward emancipation from oppression, injustice, misinformation, extremism, and so much more,” says Douglas, who is one of 90 contributors to Four Hundred Souls, A Community History of African America, 1619-2019 (One World, 2021), coedited by Kendi, BU’s Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities, and historian Keisha N. Blain.

“W.E.B. DuBois famously wrote how does it feel to be a problem?” Douglas says. With The Emancipator, “I can pull that throughline and curate commentary and ideas with a solutions focus that invites everyone into the work of dismantling white supremacy by being better informed.”

Charles Whitaker, dean of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, has known Douglas for 30 years, since she was a Medill student, editor of the school’s student magazine, Blackboard, and a Daily Northwestern staff member. And he, for one, thinks she’s perfectly suited to lead The Emancipator. “Deborah is someone who absolutely loves journalism and believes in its power to shape society, to make change,” he says. ”It’s not her life’s work—it’s her life. The Emancipator fuses all the things she cares about—storytelling, writing, showcasing African American achievement.”

Child of the Great Migration

Douglas’ journalism is rooted in her personal history as a child of the Great Migration, who came of age “in the remnant aura of the civil rights movement,” as she writes in her book, U.S. Civil Rights Trail: A Traveler’s Guide to the People, Places, and Events That Made the Movement (Moon, 2021). She was born in Chicago’s West Side Austin community, where her parents, both from sharecropper families, had found opportunity after leaving the Jim Crow South. Her mother worked for the federal government, first as a secretary and then as a Social Security claims representative. Her father was an entrepreneur who ran an auto body shop. Douglas began her schooling in the early 1970s, in post-uprising Detroit, where she lived with her mother and eventually her stepfather after her parents were divorced.

Raised in a strict evangelical Christian home, Douglas recalls not speaking much as a child. “You’re picking up these cultural cues at home and in the wider world that your presence and your voice don’t matter,” she says. She made a promise to herself to observe everything so she could become a writer who would say and write everything.

At eight, she decided just what kind of writer she would be. “I liked to read and I wanted to be pretty and I liked to write, and I started looking around to see, well, who reads and writes and looks pretty? And TV anchors look pretty. That was the kind of glamour I thought I could aspire to. I knew I would never be Diana Ross glamorous. I told my mom I wanted to be a TV anchor. My mom said, ‘Good, I think they call that journalism, you would be a journalist.’ My mom always hyped me up.”

Douglas lived for several years with her maternal grandmother in Covington, Tenn., and encouraged by some of the Black women around her, she gradually began to find her voice. Her grandmother’s neighbors across the street invited her to use their personal library and Douglas immersed herself in their books, devouring Maya Angelou, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, James Baldwin, Gwendolyn Brooks. “Their books by iconic Black authors made me feel seen and valued,” she says. She remembers thinking that when she grew up, she wanted to make sure people knew about “the fullness of the Black experience, such as I was reading about in those books.”

She came by her love of newspapers through her family. “The men would travel around from Chicago, Detroit, to the South, and they would pick up papers all along the way,” Douglas recalls. “We would sit down and read what they were reading in downstate Illinois, or in Ohio, or wherever they had been, and then compare them and talk about the issues.”

At Medill, she discovered her passion for writing about Black culture for Blackboard. “Once, in freshman year, a professor said, ‘Write an expository story,’” Douglas recalls. “So I wrote a story about how to roll your hair. That was my way of introducing culture into the mix—because I knew he’d never read a story about how a Black girl rolls her hair at night. I got a good grade.”

After graduating, she held a yearlong reporting internship that took her from the Kansas City Star to the ShoreLine Times in Guilford, Conn. Soon afterward she became a full-time reporter at the Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, Miss. While she was at the Clarion-Ledger, Douglas stumbled upon a story during an impromptu visit to her paternal grandmother, who lived in a rural part of central Mississippi, catching up with her at a church meeting where the congregation was asking for donations, in quarters, dimes, and nickels, in the names of family members. “Afterward, she says that it’s money that they raise so when you die, there’s enough money to bury you,” Douglas recalls. That anecdote became the root of her story for the Clarion-Ledger—about the Black church burial societies that helped grieving families bury their loved ones with dignity. Douglas counts it as the story from her 30-year career in journalism of which she is most proud.

Back to Chicago, and the stakes are high

Returning to Chicago, Douglas worked in publishing, finding her way back to news as editor of a health and fitness publication at Thomson Target Media. Her art director, Mike Reisel, remembers: “I had so much respect for her immediately because of her passion. Deborah doesn’t do anything halfway and she doesn’t follow anyone else’s map. Lifestyle was not going to hold her attention unless it talked about the larger issues.”

Douglas moved on to become deputy features editor at the Chicago Sun-Times. After launching the new lifestyle section, she recalls, she told her boss, the features editor, who was white, that she was ready for another challenge. He suggested that she should just relax. It was the early 2000s, and Douglas was one of a few Black journalists—and even fewer Black women—in top positions at the Sun-Times or anywhere else in mainstream American journalism. “I can’t come to work to relax,” she recalls telling her boss. The stakes were too high. She was working on behalf of “the community that has grown me, cultivated me, and sent me down here to make good decisions about what stories to put in the paper,” she told him. “And if I’m going to make good decisions, I need to be vital.”

Her editors gave her additional roles, including as library director. The library gig “was simply to fill a need, but I looked at it as an opportunity,” Douglas says. “As a Black woman in the workplace, you have to do that. My grandmother in Tennessee was a quilter and she made beautiful things from scraps. So do I.”

She saw the role as a chance “to nurture and showcase the paper’s valuable intellectual assets.” One of those assets was a Sun-Times photo of Mamie Till-Mobley with her son, Emmett, both of them beaming. Douglas made the photo available as the cover image for Till-Mobley’s 2003 book, Death of Innocence: The Story of the Hate Crime That Changed America, about the lynching of her 14-year-old son, which she wrote with Chris Benson. Douglas eventually moved to the Sun-Times editorial board, becoming a columnist.

All the time she was working in legacy media, Douglas was troubled by a sense that some people—people who looked like her—were, to use a word she coined, “depresenced” by the mainstream press, as if they didn’t really exist. ”They’re just like this invisible person who’s saying, ‘I’m here! I’m here!’ Douglas says. “And society, institutions, policies never really see you. But you’re here, living, breathing, trying to thrive.”

Douglas eventually found her way to a new approach some journalists have adopted in recent years, known as “solutions journalism.” She became a senior leader at The OpEd Project, which amplifies underrepresented expert voices, and founding managing editor of MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, which covers poverty, power, and policy.

After three decades in journalism, she says, her new position feels like the one she’d been aiming for all along. “The Emancipator’s true north is democracy,” says Douglas, quoting her coeditor Payne. “If the point of journalism is to be a pillar of democracy, where everyone has a right to pursue a higher level of society and engagement, then why shouldn’t everybody’s stories matter?”

At The Emancipator, she says, they will.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.