BU Rolling Out New Student Conflict Resolution Program

BU Rolling Out New Student Conflict Resolution Program

Listening, empathy can make difficult conversations productive, says Stacey Harris, initiative leader

The goal of the new BU Student Conflict Resolution Program is to help students make difficult conversations productive rather than rancorous, whether it’s on a hot-button topic or a mundane dispute over a messy dorm room. Photo by kieferpix/iStock

Stacey Harris knows how important it is to be heard, because for a long time she wasn’t.

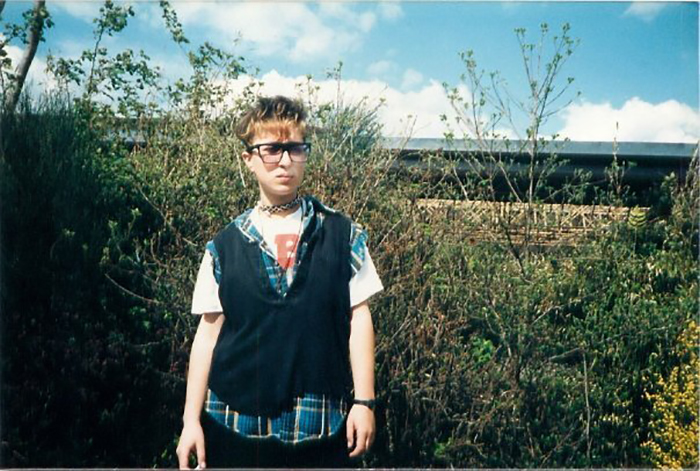

“My parents just were not expecting me,” she says. “The queer, blue-haired Harvard Square kid just didn’t work for them. They didn’t get it, so they couldn’t get me. And it was very hard. So from 13 on, I wasn’t really with them.”

In the long run she has thrived, with a happy family of her own and a career as Boston University’s associate director of Disability & Access Services, a post she’s held since 2014. But she hasn’t forgotten how difficult life can be when you can’t say what you mean or when the people you need to hear you aren’t listening. That’s a big reason why she’s spearheading Boston University’s new Student Conflict Resolution Program.

The goal is to help students make difficult conversations productive rather than rancorous, whether it’s on a hot-button topic like politics or gender or mask-wearing during the pandemic, or a mundane dispute over a messy dorm room. The program offers ways to tackle thorny subjects and set baggage aside to get to understanding. And an important part of all that is listening.

“Everybody has stuff. It’s about being human with stuff,” Harris says.

She hopes students will come to the new website now, both for the skills and tips it offers and to sign up for one of January’s inaugural workshops, in person or online, intended to help students approach their real-world conflicts in a new way.

“Students may be headed home, or planning to be on campus for the first time in the spring. There may be difficult conversations to be had over break,” she says. “Students and families may have different opinions about what the best next steps might be. The website offers an array of tools, tips, and advice to help students walk through some of them.”

Stacey Harris is trying to help students get comfortable with difficult conversations through BU’s new Student Conflict Resolution Program, which launches after intersession. Photos by Cydney Scott

Harris is the first Student Life Fellow in the Dean of Students office, and she established the Student Conflict Resolution Program with Kenneth Elmore (Wheelock’87), associate provost and dean of students. Elmore says the goal is not to change human nature, but to deal with it better.

Between the COVID pandemic, the political divide, and the racial reckoning facing the nation, it’s easy to see the ways human beings are in conflict with one another, he says. “It’s inherent. What this program does is, it says here is a way you can think about your interactions with each other. This works, whether it’s saying, ‘Can you please pull up that mask?’ or ‘Can you please, if you want to stay in my bubble, not go to a movie theater?’ And it also goes to, ‘Don’t disparage me along lines of race and class and culture, and don’t let anybody else do it, either. And let’s talk about that.’

“What does the community get out of this?” he asks. “We are going to all be better if we can talk to each other.”

January workshop sign-ups open

The inaugural January schedule is built around the four-hour course Conflict, Conversation and Community, which will be offered several times, in both one-day and two-day versions, from January 4 to 24.

Sessions will focus on topics such as, How to tell friends to put a mask on, stop stealing your food, or turn down the music, while staying on good terms; How do you fix things after you have let someone down? How to set the stage for a hard conversation when you really want the relationship to continue; Are you a good listener?

With everything going on in America and the world, “we’re all rife with, and primed for, reflection, so this comes at a good time,” Elmore says. “And just from a basic level, you are not going anywhere anyway, with the pandemic going on. So you might as well take some time to do a reflective activity with other people.”

Just recently, he notes, one group of students painted a serious message on the BU Rock, only to see it painted over the next day by another group. “That’s a conflict and a disrespect that’s happening. This program is perfect for that.”

The upcoming Conversations Can Be Hard workshops will help those who find it hard to speak up in the first place: “Let go of those nerves. Practice asking deeper questions. Explore telling your story.”

The website also features tools such as the How to Have a Conversation guide, which covers ways to get your message across so the other person can really hear it and mindful listening. It tackles barriers to good communication—including misunderstanding, making assumptions, and not being truly present—plus a favorite Harris skill, practicing empathy.

“There’s this relief that comes from connection and human interaction,” she says. “I think we’re all lost unless we are connected in some way.”

The I Think I Need Help with a Conflict page will help students arrange for peer conflict coaching or for a facilitated dialogue circle, where a neutral staff member will help a group of students—a study group, a housing suite, a club, for example—navigate a problem within that community.

There is also a BU HUB course in the works for the fall.

Acting out conflicts

The program was first piloted in early fall with a series of COVID-centric workshops, Conflict—Navigating the Hard Stuff in This New World. Workshops can be customized for specific groups or departments. In the fall, Harris held both online and in-person workshops for undergraduates from the College of Fine Arts, with role-playing scenarios for students in creative communities such as theater casts and music ensembles.

Graphic design student Gabriela Ferrari (CFA’22) and another person role-played as “theater majors who were angry at a third person who had been posting stuff online from our rehearsals,” Ferrari says. “The stuff we were doing was so emotional and personal that we were angry at that person for sharing it online. And their side of the story was that they thought it was really cool and were excited about theater and wanted to share it. And the rest of the group had to try to get us to see eye to eye.

“Stacey was really emphasizing to go really slow,” Ferrari says. “‘How are you feeling, what are you thinking?’ And she had little things, like not saying, ‘Do you want to go first?’ because someone might think you’re taking sides, but instead asking, ‘Who wants to go first?’ Little things that you’d never think of.”

We are going to all be better if we can talk to each other.

“In the arts, relationships are such an important component,” says Ruthie Jean (CAS’95, Wheelock’98), CFA associate dean for academic programs and enrollment. “Situations were arising where we felt our students needed more professional development skills in how to work with other people. We were talking about this, and as if she’d heard it in the ether, Stacey called me.

“I hope students can learn to engage in differences they encounter with peers and faculty and staff and address them with respect and honesty,” Jean says. “It’s not that right now we’re seeing tremendous amounts of conflict with people raising things in poor ways, it’s just that I think people aren’t talking about some of these difficult things. The more our students can have these conversations in respectful ways, I think, the further their artistic challenges, messages, visions can go.”

Feedback on the pilot workshops was “deeply encouraging,” Elmore says, “because we had people starting off, ‘Ehhh, I dunno about this,’ who in the end said, ‘This is really good. I needed that reflection, and I picked up some things that are going to be really helpful for me. When can I do this again?’ And also, ‘Can you train me up to do this on my own?’ And that’s really where the goal should be. How do we put enough of this into the stream of our community so people can do this themselves and with each other?”

Making hard times matter

Harris is careful not to reopen old wounds with her parents, but acknowledges that her difficulties as a teen drive her work on communication.

“I think they worked really hard to fit me into a box I couldn’t fit into. I went to Barbizon Modeling School when I was 13,” she says with a chuckle, “and there were other interventions to fit me into what they thought I would be,” including a stint at an alternative school for girls. She spent her high school senior year couch-surfing at a friend’s place.

She entered Curry College through a program for students with dyslexia, graduated with a double major in communications and philosophy, and later earned a law degree at Suffolk University. She might not have made it, though, she says, without “these moments I harness now, where people just reached in through the lost teenager to the person inside to say, ‘I get you.’”

Those include a former president of Curry, who stood up for her when some students threatened to protest her commencement speech—chosen in an anonymous competition—because she was gay. “It was the most validating thing. After so much judgment, she said, ‘You got this.’ I keep that with me,” Harris says.

She worked as an appeals investigator for the Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services and as a disability project coordinator for the city of Cambridge, among similar jobs, before moving into higher education. At the same time, she got trained as a family mediator.

Elmore says he has confidence in Harris’ running the conflict program, first of all “because she cares. That’s a big piece. She just cares. She is a thinker. She is empathetic. And that’s what you need. She got the knowledge she needs, too. But heart is hard to replace. And she’s got the heart for this.”

Harris has a not-so-secret weapon. Her first real education in conflict resolution came from an unexpected source.

“I am dyslexic, had a lot of struggles reading, and my parents told me that I needed a trade,” she says. So, while in college, she also went to hairdressing school, “which turned out to be the best thing I ever did, because I learned to communicate with every kind of human. You can’t cut their hair badly just because they’re rude!”

Now she is one of a very few university administrators in America—perhaps the only one—with the kind of advanced education in human nature that you get by spending a few years with scissors in hand at SuperCuts.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.