Reimagining Ansel Adams

BU alum Karen Haas has curated an MFA show about one of the foremost US photographers

Karen Haas (GRS’89), Lane Curator of Photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, conducts a tour of Ansel Adams in Our Time, an ambitious retrospective that is divided into eight galleries and features almost 200 works. Photo by Cydney Scott

Few 20th-century photographers are as well known as Ansel Adams. His iconic black-and-white images of snow-capped mountains, waterfalls, deserts, and moonlit skies have defined the American West for generations of Americans.

“I think these are the kind of photos that are so ingrained in our minds that even if we never go to Yosemite, these are images we have of that place,” says Karen Haas, Lane Curator of Photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, who has just mounted a spectacular retrospective of Adams’ work, Ansel Adams in Our Time, on view through February 24. Haas, who earned a master’s in history of art and architecture from BU in 1989, says that when she visited Yosemite for the first time 15 years ago, she “had to laugh because I was struck that it was in color.”

The ambitious retrospective, divided into eight galleries, features almost 200 works and contextualizes Adams’ photographs by including prints by 19th-century government survey photographers like Carleton Watkins and Eadweard Muybridge, whose work would have a huge influence on Adams. Further, Haas has added work by 23 contemporary photographers preoccupied, like Adams, by the Southwest, the wilderness, and issues affecting the environment.

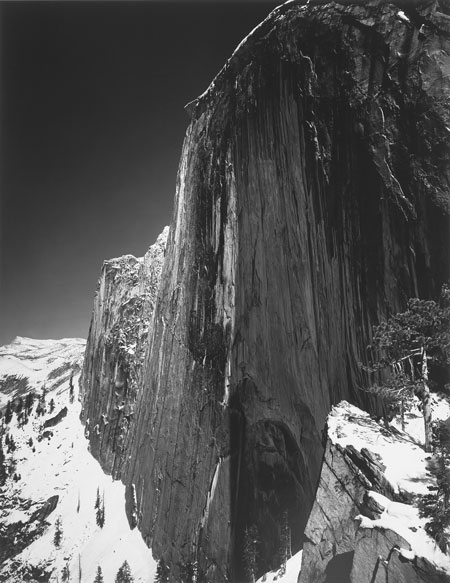

“My thought was, Ansel Adams is one of these artists who has always been treated like a singular figure, like he came out of nowhere, was influenced by no one,” Haas says. The exhibition’s first gallery is designed to refute that idea. She has displayed many of his most familiar works—his self-proclaimed “Mona Lisas”—including Monolith, The Face of Half Dome, Yosemite, 1927, alongside a mid-1860s album of photographs of Yosemite by Watkins. The album, which was produced for the California Geological Survey, convinced Abraham Lincoln and Congress—in the middle of the Civil War no less—to designate Yosemite as protected land.

“This was the kind of thing that was not lost on a young Ansel Adams, who went on to become such an environmental advocate,” Haas says. Adams, as the exhibition notes, fell in love with Yosemite as a teenager while on a family vacation and began photographing its magisterial vistas with a Kodak Brownie camera he’d been given.

Managing a vast collection

The Adams retrospective is the latest high-profile show Haas has mounted since she arrived at the MFA in 2001. Among others are 2015’s Gordon Park: Back to Fort Scott and 2017’s (un)expected families, which explored the different definitions of family as captured by photography.

As the Lane Curator, she is responsible for more than 6,000 photographs by American modernists, including Charles Sheeler, Edward Weston, and Imogen Cunningham, given to the museum by former MFA trustee Saundra Lane and her late husband, William Lane, in 2012. (All of the Adams photographs in the current show are drawn from the Lane Collection.)

Haas’ interest in photography was first sparked while working at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum after she earned a BA in art history from Connecticut College. She acknowledges that the Gardner, with its emphasis on paintings, tapestries, and decorative arts, “might seem like the last place on earth to find photographs,” but Gardner had compiled extensive photography albums documenting her travels, art collecting, and building the museum, and Haas became fascinated by them. “I had also met and fell in love with a photographer around that time, which helped,” she says.

She then decided to pursue a master’s degree in art history at BU, specializing in American painting, but that changed after she took a photography class with Carl Chiarenza (COM’59, GRS’64), then history of art and architecture department chairman and director of graduate studies. Taking the class made her realize she wanted to focus on photography. At the time, BU had one of the few programs in the country offering a concentration in the history of photography.

“There is a very vibrant community of photo historians and curators still in the area that have come through that program over the last 20 to 30 years,” Haas says. “Even those who are farther afield still stay in touch with each other.”

In addition to the Gardner, Haas did curatorial stints at the Addison Gallery of American Art, in Andover, Mass., and the BU Art Gallery and worked for various Boston area private collectors. Her first exposure to the Lane Collection came in 1995, when she was hired by Saundra Lane to organize the photographs amassed during the couple’s marriage.

Haas says that what drew her to photography is its ability to incorporate what she sees as a perfect mix of accessibility and mystery. “To work on a subject that for many people feels extremely familiar is appealing from the standpoint of a museum curator, wanting to reach as large and diverse a public as possible,” she says. “But it is also a medium with many unexpected aspects to it. Photographs have, on the one hand, a seemingly indexical relationship to the world around us, but they also have a mysterious abstraction built into them—their transformation of the world from 3-D to 2-D, sometimes from color to black-and-white—and that is one of my favorite aspects of the field.”

Presenting a multifaceted Ansel Adams

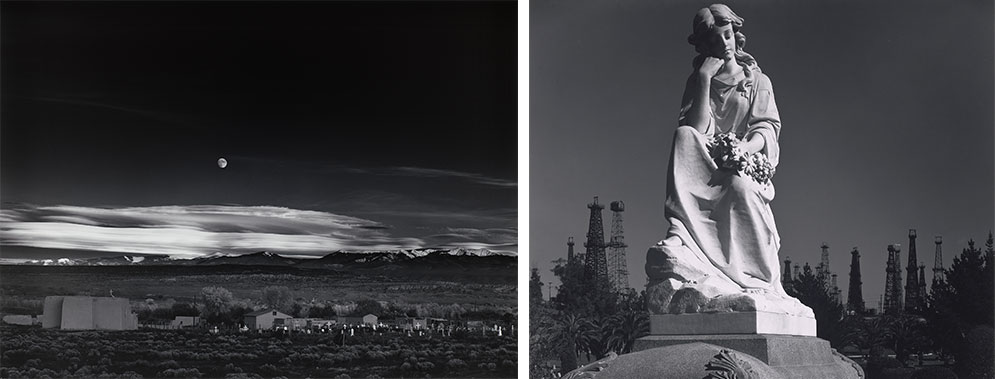

Haas says that one of the exhibition’s goals is to present a multifaceted Ansel Adams to the public. Yes, it includes many of his best-known works, like Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1941, but there are also unexpected and surprising photographs that emphasize his versatility, images like Cemetery Statue and Oil Derricks, Long Beach, California, 1939, a looming statue in a cemetery set against a backdrop of oil derricks. The composition is eerie, nothing like the artist’s grand landscapes. One gallery is filled with a series of small photographs, like Pine Forest in Snow, Yosemite National Park, about 1932, that show his ability to work on a smaller scale, capturing more nuanced and delicate scenes.

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1941, Ansel Adams (left); Cemetery Statue and Oil Derricks, Long Beach, California, 1939, Ansel Adams (right). The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

As visitors enter the exhibition, they are greeted by a blown-up photograph of Adams taking a picture from atop his car in the Yosemite parking lot. Haas says it’s an important reminder of how he worked and his ability to work around images that encroached on the pristine vistas he was trying to capture.

“It’s not that he was climbing through the wilderness with no one around him, with all his equipment on his back,” she says. “He is on top of his car so he can avoid the parking lot, which anyone who has been there knows is there. And I don’t think that lessens the experience of Adams’ photographs one iota. In fact, I think it makes them more interesting.”

Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of Mount Moran and the Snake River from Oxbow Bend, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, 2011, Abelardo Morell

Another impetus for mounting the Adams show, Haas says, was the chance to explore his impact on contemporary photographers. In a later gallery, in an almost tongue-in-cheek nod to the photo of him on his car, is a stunning series by contemporary Boston-based photographer Abelardo Morell, who photographed the same views as early photographers of the American West, including Adams, but with a twist. Morell set up a tent fitted with a periscope and mirror contraption in the parking lots of various national parks. The mirror directed the periscope’s outside view onto the ground in the tent, which he then photographed. Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of Old Faithful Geyser, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, 2011, for instance, shows the geyser in all its glory reflected onto a mottled background of parking lot detritus, creating a beautiful patina effect. Morell’s pieces underscore national parks as tourist destinations.

Included also is work by feminist photographer Catherine Opie, whose fuzzy, out-of-focus images of notable Yosemite views offer a different perspective from Adams’ work. His stark black-and-white landscapes contrast with Opie’s photographs, captured in soft but vibrant creamy hues. The images are still recognizable but merely alluded to—it’s the same waterfall, but not. Opie has taken control of the narrative and caught it through a contemporary lens, her hazy renderings perhaps an allusion to our fading attention span in this increasingly digital age, when the environment demands our attention more than ever.

As Haas and the exhibition make clear, Adams is part of a continuum of artists who are drawn again and again to the same striking landscape, and each of them manages to capture it through a distinctive lens. Ansel Adams in Our Time shows us that Adams is part of an ongoing conversation about the enduring legacy—and fragility—of the natural world.

Ansel Adams in Our Time is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, 265 Huntington Ave., Boston, through February 24. Find directions here. Find hours and admission here; free for BU students, faculty, and staff with a valid ID.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.