Tagged: psychology

Time to Activate

Sick children are cared for by parents, but what happens when they grow up?

Many children in the United States live with chronic disease; Type 1 Diabetes, sickle cell, arthritis, asthma, and cystic fibrosis are common diagnoses. Yet once children grow into adulthood and age out of the pediatric healthcare system, they often find themselves unprepared to advocate for their own medical needs. In the pediatric healthcare system, the child’s perspective is always important although ultimately the child’s guardian is legally responsible (e.g. signing informed consent for a procedure). Once the child reaches the age of 18 (age of majority in most states), the child retains full legal responsibility for choosing and consenting to treatments. With the sudden diminishment of the caregiver’s legal authority, the responsibility becomes the child’s to make the best decisions for his or her own body and lifestyle.

Without a gradual introduction to the realm of consent, a child cannot possibly be expected to understand the complexities of being a medical advocate. Effective transition is different from efficient transfer, where transition is the long-term accumulation of a child’s medical responsibility and transfer is simply the physical move to an adult care facility.1 Merely sending a child and his medical record to a new adult provider is not synonymous with actually preparing the child to care for his chronic illness into adulthood. Ultimately, the latter will be most advantageous to children, families, physicians, and the medical system at large.

Getting Started

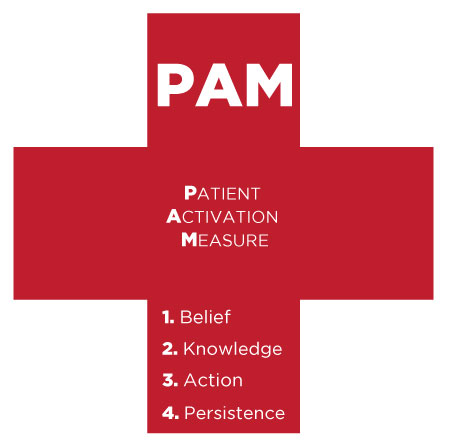

“Patient activation” as the mechanism for achieving meaningful and long-lasting involvement in pediatric chronic illness is a much-debated topic. Patient activation is defined by the patients’ completion of four stages: 1) understanding that their role is paramount 2) having the appropriate understanding and certainty to make a decision 3) having taken actual action towards health goals and 4) persisting in the event of adverse situations.2 It has long been known that actively engaged patients report improved health outcomes) and that successful chronic illness management skills can increase function, as well as minimize pain and healthcare costs. 3,4 The benefit to pediatric patients would be tremendous – particularly to their long-term physical, social, and emotional functioning. The problem remains: even with patient activation conceptualized, how can pediatric patients be ‘activated’?

Will Patient Activation be able to give sick children a more active say in their health once they are older? Photo Credit | Robert Lawton via Wikimedia Commons

The solution is a multifaceted approach, targeting the child, family, medical team, and medical culture at large. If medicine can be increasingly viewed as “consumer driven,” individuals may be less likely to accept doctors’ opinions without ensuring their own voice had been heard.2 For example, few people would tolerate going to a restaurant and being told what to order. Yet medical decisions are often chosen with the patient’s complete understanding.1

Medical education must be progressive and developmentally appropriate for patients and their families; too much too fast would only serve to be overwhelming. Nevertheless, patients and families must be empowered. This inevitably depends on the disease, age of child, culture considerations, and more. For example, a child living with arthritis needs an emphasis on physical activity as he matures. On the other hand, a child living with HIV should be educated about safe sex practices only when it is developmentally and culturally appropriate, involving the family along the way. Additional concerns, such as procuring health insurance with a pre-existing condition and medication prescription, are important to discuss with the child and family as transition begins to further success.

Achieving Independence

How can this success be measured? The Patient Activation Measure (PAM) was developed by Dr. Judith Hibbard, a professor of Health Policy at the University of Oregon, to assess patients’ degrees of involvement in their care. There are four subscales, which include ‘Believes Active Role is Important’ (e.g. “When all is said and done, I am responsible for managing my health condition”), ‘Confidence and Knowledge to Take Action’ (e.g. “I understand the nature and causes of my health condition(s)”), ‘Taking Action’ (e.g. “I am able to handle symptoms of my health condition on my own at home”), and ‘Stay the Course under Stress’ (e.g. “I am confident I can keep my health problems from interfering with the things I want to do”). 2 It is evident that these four core values of patient activation underscore the intersection of belief that the patient is an important actor in their medical care, thorough education of disease and lifestyle, and an active role. In a study with an adult population, the PAM was significantly related to health-related outcomes. Patients who score as being highly activated also experienced improved health-related outcomes when compared with their counterparts.5

The PAM is a useful tool for measuring patient activation, but the problem persists – how do we meaningfully activate pediatric patients? The answer in part lies in transitions clinics, an innovation that patients have been benefiting from for several years. Transition clinics occur within a given specialty (e.g. Rheumatology) with the goal of providing additional resources to prepare a child for adult care: primarily educational programs and skills training.6 The age at which a child becomes engaged in the transition clinic will varies in light of the age at diagnosis, social support, disease severity, and developmental stage. For instance, a child diagnosed with an illness at age fifteen should not begin the transition clinic right away, while another child diagnosed with the same illness at age eight may find the transition clinic appropriate at age fifteen.

The PAM is a useful tool for measuring patient activation, but the problem persists – how do we meaningfully activate pediatric patients? The answer in part lies in transitions clinics, an innovation that patients have been benefiting from for several years. Transition clinics occur within a given specialty (e.g. Rheumatology) with the goal of providing additional resources to prepare a child for adult care: primarily educational programs and skills training.6 The age at which a child becomes engaged in the transition clinic will varies in light of the age at diagnosis, social support, disease severity, and developmental stage. For instance, a child diagnosed with an illness at age fifteen should not begin the transition clinic right away, while another child diagnosed with the same illness at age eight may find the transition clinic appropriate at age fifteen.

Ultimately, the issue in part returns to the present medical culture: how doctors are trained to communicate with patients and the historically paternalistic medical model. It is plausible patients with doctors that have a strong and respect-filled relationship will have more positive medical experiences compared to those with poor patient/physician relationships. Thus, strengthening this relationship should be tandem to encouraging and initiating a transition process for pediatric patients.

References

1Peter et.al, 2009. Transition From Pediatric to Adult Care: Internists’ Perspectives. Pediatrics. 123(2):417-423.

2Hibbard et al., 2004. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and Measuring Activation in Patients and Consumers. Health Serv Res. 39(4 Pt 1): 1005–1026.

3 Von Korff et al., 1997. Collaborative Management of Chronic Illness. Annals of Internal Medicine.127(12):1097–102.

4 Glasglow et al., 2002. Self-management Aspects of the Improving Chronic Illness Care Breakthrough Series: Implementation with Diabetes and Heart Failure Teams. Annals of Behavioral Medicine.24(2):80–7.

5J. Greene and J. H. Hibbard. 2011. Why Does Patient Activation Matter? An Examination of the Relationships Between Patient Activation and Health-Related Outcomes. Journal of General Internal Medicine.

6 Crowley, et al. 2011. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. ADC. 1:1-6.

Jennie David (CAS 2013) is a psychology major from Nova Scotia. She hopes to use her personal experience with Crohn’s Disease to support and inspire chronically ill children as a future pediatric psychologist. Jennie can be reached at jendavid@bu.edu.

Tagged as: medicine, patient care, psychology, pediatrics

Psyching You Out

Interesting psychology experiments that have helped us understand ourselves.

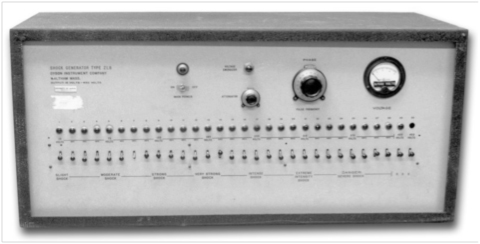

The shock box used for the infamous Milgrams experiment, which revealed much about the human mind. Photo Credit | psichi.org via Wikimedia Commons

Psychology has forced humans to question ourselves: our personality, our thoughts, and our experiences. What do psychology experiments reveal about how we behave and interact with others? Years of research have yielded some of the best and the brightest classic experiments and helped us to understand who we are- and who we might become.

Fake It Til You Make It

Elizabeth Loftus was a researcher who dedicated her life to studying “false memories” and the misinformation effect. To study false memories, she conducted the ‘Lost in the Mall’ experiment, in which she asked participants to imagine and describe an experience of getting lost in a mall.1 To strengthen their recollections, Loftus gathered fake testimonies from participants’ families or friends about the imagined event. Loftus discovered that upon prompting her participants, those interviewed came to believe that they had actually once been lost in the mall. In a similar study, Loftus’s participants watched a car crash scene and were asked afterwards to describe what they had witnessed.2 Interviewers tested the effect of bias upon the participants: leading them with phrases such as, “When the blue car smashed into the red car…” Sure enough, depending on the leading phrase, the crash would be remembered differently by each witness. Watch more here:

Loftus’s discoveries prompt us to wonder the obvious – how do we know what we really remember and what we’ve colored in between the lines? Watch out for similarities between your ‘recovered’ memory and a favorite book or movie – you just might have borrowed the storyline.

Follow the Leader

After the world suffered the atrocities of WWII, people struggled to understand the lack of ethics behind the Nazi’s apathetic terror tactics. Researcher Stanley Milgram pondered this perplexity; and he was determined to figure it out. He designed an experiment to evaluate the importance of ethics and authority by using a ‘learner’ and a ‘teacher’ simulation.3 The subjects (teachers) were falsely led to believe that another person (a learner) was in a separate room, and that it would be their responsibility to ask the learner a predetermined set of questions. If the learner answered correctly, the teacher would move on to the next question. If, however, the answer was wrong, the teacher was instructed to dose the learner with an electrical shock, which increased in intensity with each question. Milgram was interested to see how easily the teacher would follow directions to shock the learner even if they knew the detrimental effects.4 Watch more here:

So what happened? Ordinary people knowingly and willingly gave their imaginary partners enormous shocks and in turn the research community was appalled by the apparent ‘following orders’ outcome. Yet just because someone has authority does not mean you must obey them at all costs! At the end of the day, follow your own moral compass and retain your right to say no. Be your own leader.

To eat, or not to eat

A big, puffy pack of marshmallows sure looks tempting. But by and large we’re able to resist – or at least until we’re left alone with them. How does this trait to resist temptation develop? Were we always able to resist? In a classic developmental research study at Stanford by Walter Mischel, children were brought in a room and told that the researcher had to leave for a moment – leaving a marshmallow on the table – and if the child waited, they would bring back a second one.5 If the child ate the first marshmallow, there would be no seconds. The researcher leaves, and the child’s inner-debate over the treat begins. To eat or not to eat? Of the 600 children who were part of the study, only 1/3rd were able to resist temptation and obtain a second marshmallow. Many of the children tried to cover their eyes or distract themselves, but the temptation would prove to be too great for their young age. See the experiment in action here:

Can you resist temptation? You are not a little kid anymore and can all the cookies you want. But it’s a reminder that you do have those delay of gratification skills and can wait until you’re a little less full to chow down on some more sweets.

Psychology experiments help inform us about how our brains function and how we are wired to react and behave in various settings. We can be smart consumers of research by reading articles with a critical mind and a social awareness to understand how it relates to our immediate lives. This way, we will better comprehend our world, our friends, and our own lives.

References

1False memories - Lost in a shopping mall - Elizabeth Loftus.flv. YouTube. (n.d.) YouTube - Broadcast Yourself. Retrieved March 20, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8xPfJ8cPhs&feature=related.

2Creating False Memories. (n.d.) UW Faculty Web Server. Retrieved March 20, 2012, from http://faculty.washington.edu/eloftus/Articles/sciam.htm.

3Stanley Milgram Experiment (1961). Experiment-Resources.com . A website about the Scientific Method, Research and Experiments. (n.d.) Experiment-Resources.com. A website about the Scientific Method, Research and Experiment. Retrieved March 19, 2012, from http://www.experiment-resources.com/stanley-milgram-experiment.html.

4Milgram Obedience Study. YouTube. (n.d.) YouTube - Broadcast Yourself. Retrieved March 20, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W147ybOdgpE&feature=related.

5Kids Marshmallow Experiment . YouTube. (n.d.) YouTube - Broadcast Yourself. Retrieved March 19, 2012, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6EjJsPylEOY.

Needing Fixing

Promoting resilience in pediatric autoimmune diseases.

Half of all Americans will deal with a chronic illness in their lifetime.1 This overwhelming statistic is curiously a little-known fact, with chronic illnesses rarely discussed and poorly understood by those who do not suffer from disease. Twenty percent of the American population suffers from an autoimmune chronic illness, including Crohn’s disease, arthritis, asthma, and lupus.

Autoimmune diseases generally begin in early adolescence and develop a cyclic pattern of active disease, or ‘flares’, and remission. In these types of conditions, the immune system is stimulated unnecessarily by an unknown cause and perceives an individual’s organ or organ system as a pathogen, attaching and destroying normal tissue as if it were a disease-causing bacteria or virus.

Since many of these disorders begin in youth, both physiological and psychological treatments are critical to ensuring overall health. Most autoimmune diseases are invisible from the exterior; it is nearly impossible to discern if a person is ill from their physical appearance alone. Therefore, people with autoimmune illnesses often fight to legitimize their diseases, whether it is to a doctor, professor, or a peer who cannot ‘see’ the problem. Although autoimmune diseases are typically not terminal, the severity and uncertainty associated with their prognosis often goes unrecognized due to the lack of physicality associated with the disease and the severe limitation of awareness surrounding such illnesses.

Children are a fascinating subset of this population, for patients with pediatric autoimmune diseases prove to be both the center of the care and somehow also the individual with the least amount of control. Yet, once the child transitions to adulthood, they are expected to advocate for themselves despite the fact that they have not been engaged in their healthcare and are offered no coping skills.

Family Matters

The FAAR program provides guidance for family interactions involving children with autoimmune diseases.

The inevitable involvement of the patient’s parents and siblings can act as a catalyst for behavioral problems of the family’s own, namely depression, social isolation, anxiety, and jealousy. Siblings can easily become jealous of the attention the parents or other authority figures in their lives give to the ill child, and the amount of family time that is concentrated on his or her medical care. The optimal family situation provides comfort and openness in discussing the child’s disorder, while maintaining both the child and family’s identity. University of Minnesota Professor Joan Patterson’s Family Adjustment and Adaptation Response (FAAR) Model holistically captures this idea within nine basic criteria.2

1) The family must balance the child’s illness with the family needs and interests of other family members.

2) Parents should maintain clear family boundaries between themselves and their children in regards to discipline, bed times, and household chores.

3) Parents and their children can develop communication competence by ensuring that the child understands important medical information that pertains to them. Through modeling effective communication competence, parents will be able to instill in their children the ability respond to others’ needs and with the appropriate words or actions.

4) The family should try to attribute positive meaning to their situation by focusing on newfound responsibilities instead of their fear of the disease itself.

5) Parents should demonstrate flexibility by allotting as much time to family activities (like a sporting game) as to medical obligations. A child whose family is able to ‘go with the flow’ will experience life as a “normal kid” as opposed to a young adult dealing with an illness.

6) Parents must commit to the family as a unit, remaining a “Mom and Dad” as opposed to separating the sick child from his or her caregivers.

7) The family can engage in active coping skills, including modeling positive ways to deal with stress aloud, using realistic thoughts, employing muscle relaxation techniques, and healthy sleep patterns.

8) The family must maintain social integration within their own household and the neighborhood/community.

9) The family needs to develop collaborative relationships with professionals, including doctors, in order to make decision that is satisfactory to everyone involved in the child’s care, especially the patient. This is a key factor to the child’s immediate and long-term success. The medical professional relationship leaves much to be desired in terms of listening to the child’s needs and wishes. Establishing a collaborative relationship builds a safe relationship where a child can express their desires and fears of their treatments to choose the best therapy.

While the FAAR model holds great potential to engage an entire family affected by chronic illness in order for it to be as successful as possible, it mostly is maintained as a theory and not necessarily as a treatment protocol. However, the best implementation would be giving the parents the guidelines to this model and having an initial therapy session to initiate the practice. As simple as it seems, the most effective behavior is openness between parents and children, while maintaining the boundaries of parent and child, to ensure that each child gets equal treatment and attention by the parents. This behavior exhibited by the parents is expected to be mirrored by the children, thus eliminating further stress and issues such as sibling jealousy.

Think About It

Interestingly, the most important indicator of a patient’s prognosis is not the diagnosis, but rather the individual’s innate attitude. This attitude derives mainly from how the child feels about the disease without any outside influence, but parents and/or other important figures’ reactions play a huge role in how a child internalizes their ailment. For example, a patient diagnosed with mild asthma who is deeply in denial and very depressed has a poorer prognosis and quality of life than a patient with severe asthma who has a positive outlook. The evidence indicates not only the mind exacerbating physical symptoms, but also a strong interplay between stress and immune functioning. Factors such as a positive attitude, an effective social community, and cognitive behavioral stress management strategies are consistently linked to better immune functioning. Conversely, chronic psychological stress, fear before surgery, and coping strategies of denial or loss of control are associated with poorer immune functioning. It deserves to be stressed that the relevance to the pediatric population is that children have not yet had the natural – or facilitated – opportunity to develop successful coping strategies and social support of their own. Thus, such a system that accommodated for the unique position of this population has the potential to optimize their care and success.

Children with chronic autoimmune illnesses face a unique battle. In many ways, they are as not fully autonomous or even aware of what is coming due to their present stage in life. Children do not always understand the extent of their illness as easily as they can perceive that they are “different” from their peers.3The chronic cyclic nature of an autoimmune disease comes at the cost of a child’s education, as severe symptoms may force the child to miss school or even be hospitalized. Diseases such as Crohn’s, which requires a child to make frequent emergency trips to the bathroom, may not only become emotionally embarrassing, but functionally problematic during school or other activities. These children appear in the center of their medical world as both a dependent third party and the one to endure the treatment. In addition to the power that is stripped from them by their diseases, these children must face the struggles of daily life and peer groups who are rarely empathetic to their plight.

All Together Now

"The FAAR model should provide great support for the ill child and the family.In many ways, fragments of the FAAR model have already been implemented within family relationships. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is often the first therapy used to readjust a person’s thinking into a more adaptive style to interact with the world and their emotions in a more relaxed manner. It employs ‘realistic thinking’ to help the individual see what will most likely happen instead of the improbable anxieties the person presents in therapy. In a disease like arthritis that often requires physical therapy, this is often done in a group format. The proposed therapy works like a group CBT arrangement, aiming to address the importance of social support with peers and the optimal cognitive style, coping skills, and stress management. Within the family setting, the use of the FAAR model should provide great support for the ill child and the family at large. On the side of the medical professionals, it is critical to the process for education about using child-friendly language and helping to preserve the childhood of their patients.

Although children with autoimmune diseases generally end up living different lives than their peers, at the heart of their care needs to be a reminder that they are indeed children and every opportunity should be made available to them. Providing children with CBT and coping strategies coupled with the FAAR intervention, their healthcare can be optimized to foster and sustain their resilience as they develop and face new and challenging medical situations. While no family dreams of having a child with a chronic illness, just because their life is not ideal, does not mean it cannot be a beautiful one.

References

1American Autoimmune and Related Diseases Association, Inc.

2Patterson, J. M. (2002). Understanding Family Resilience. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(3), 233-246.

3Patterson, J., & Brown, R. W. (1996). Risk and Resilience among Children and Youth with Disabilities.Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 150, 692-698.