Steve Ramirez and the Malleability of Memory

If you ask Steve Ramirez, PhD, what he likes most about working in the Neurophotonics Center at Boston University, he won’t hesitate to tell you it’s the camaraderie and the sense of shared support that pervade the place.

“I really enjoy that the community embraces this kind of collegial and team-oriented approach to science which I love. People here are very comfortable with sharing success,” says Ramirez, an assistant professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences at BU and principal investigator of the Ramirez Group in the Center.

“It’s like a trip to Mars. One person alone doesn’t get to Mars. You need all the people in NASA. Have you seen the videos of everyone in a NASA control room celebrating an achievement together, jumping up and down and high-fiving each other? In my world, that’s how all of science should be.”

And in the Neurophotonics Center, he adds, that’s how science is.

To be sure, there’s no shortage of success to be shared. Since moving his lab to BU in 2017 – since returning home, as it were; he had been an undergraduate here and was well acquainted with both the systems neurology program and the Photonics Center – he and his group have gone from strength to strength, particularly in looking at neural circuit mechanisms of memory storage and retrieval and how these might be manipulated in treating a range of psychiatric diseases and disorders.

Basically, they want to know, can we selectively edit memories? Like in the science fiction movies Total Recall and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind but here in the real world, using lasers and genetic engineering. For example, can we identify and suppress fear memories associated with post-traumatic stress disorder? The answer appears to be a resounding yes. Ramirez and his team have made tremendous strides, not only in demonstrating the fundamentals of how such an approach might work but also in advancing ever closer to practical application.

Even more recently, they have used the cutting-edge technologies in the lab to show how certain social interactions may help access previously held memories: an intriguing finding, especially considering the isolation many have experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The intersection between memory and the social dimension of the world is a very powerful one,” Ramirez says. “Both are well studied on their own, but the intersection between the two is less well so. The fact is, socializing can strengthen what already exists in the brain, including memories. We now think we’ve found a mechanism in animal models to bring memories back online through socializing.”

In discussing his lab’s many achievements, Ramirez returns to the idea of community and the importance of working together as a community – very purposefully including and encouraging the younger generation of scientists, who in other environments don’t always have the freedom to contribute as fully as they are able.

“I like to tell students, ‘Let’s think big,’ ” he says. “ ‘We can get to Mars. Now what would it look like to get to Jupiter?’

“The students here are so remarkably good at thinking big and being proactive about research. It really is a testament to the culture of the Neurophotonics Center, their graduate programs and all the different umbrellas at BU.”

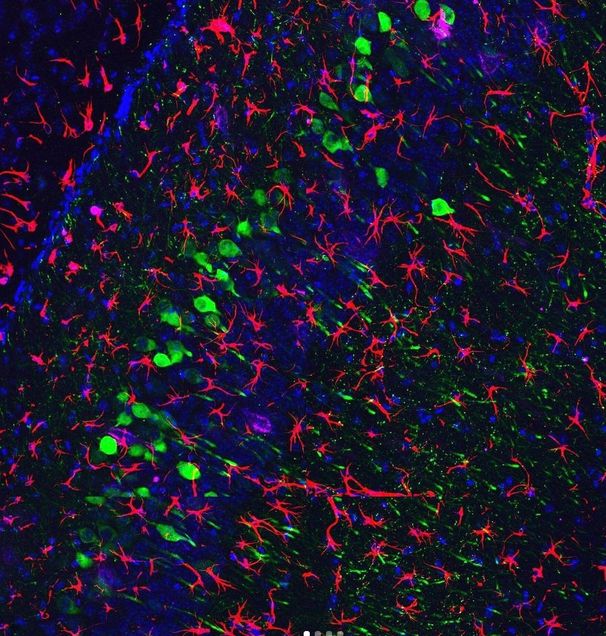

In the image at the top of the page: Ramirez (front left) and members of his lab