On Wednesday, October 17th, Dr. Karilyn Crockett joined the Initiative on Cities to discuss her book, People Before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. Her research examines infrastructure and urban development in American cities in the 20th century. People Before Highways is an investigation into the grassroots anti-highway movement in Boston in the ’60s.

Dr. Crockett is a Lecturer in the Department of Urban Studies & Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and former Director of Economic Policy & Research for the City of Boston. She holds a PhD from the American Studies program at Yale University, a Master of Science in Geography from the London School of Economics, and a Master of Arts and Religion from Yale Divinity School. Her book is based on her dissertation, which is also entitled People Before Highways.

At the core of Dr. Crockett’s discussion was her inquiry into what drives people to collectively gather to fight for a cause, especially in the context of social movements. The anti-highway movement in Boston was a remarkable effort shared by thousands of Boston residents from an array of backgrounds, joined together to prevent the undertaking of an infrastructure project that would debilitate several neighborhoods. Her research into an era of remarkable activism and collaboration unveiled the story of some of Boston’s most unique communities and the residents who comprise them.

Throughout the discussion, Dr. Crockett highlighted the intense curiosity that spawned her inquiry into this subject. “How do social movements start? What is it about the relationships and experiences of these individuals that became important?” questioned Crockett. “What is it that compels any of us to take to the streets, or to put yourself personally in the position? Is it outrage? Is it the presence of a bulldozer? Is it the threat of the law?”

Dr. Crockett began by citing the Federal Highway Act, which was signed into law in 1956 by President Eisenhower. The act allocated a significant amount of federal money to establish a national highway fund, which was the impetus for the development of the nation’s vast interstate system. Thus began a massive infrastructure project that would ultimately produce over 41,000 miles of interstate highway across the United States.

As beneficial as a national interstate system is, however, the development of the interstate had social, economic, and political implications in the communities through which it was constructed. Brown v. Board of Education passed two years prior to the Highway Act, in 1954, and the government had attempted to integrate formerly segregated institutions and communities. But the development of an interstate highway system enabled urban planners to redraw lines across communities and completely steamroll over low-income, multiracial neighborhoods.

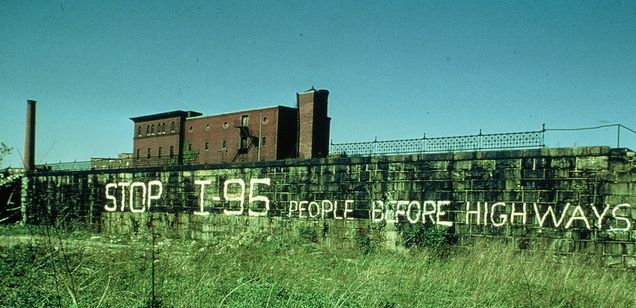

In 1948, the city of Boston had started to design a comprehensive infrastructure plan that would construct multiple highways across and through Boston, and a sudden influx of new federal funding finally provided the capital needed to begin the project. The extension of the I-95, however, in addition to other projected highway plans, became a critical issue for residents from several communities. Not only would these highways displace thousands of people, ruin land, and disrupt entire communities, but it was evidently a project designed for those living in suburban neighborhoods. The interstate neglected Boston residents who came from low-income, multiracial communities; these working-class Bostonians did not drive cars, and their neighborhoods and communities were targeted in an effort to make Boston more accessible to those living in wealthy suburbs.

The cover photo of the book depicts protestors congregated outside of the State House, coining People Before Highways as the official slogan of their movement. The climax of the protest took place on January 25th, 1959, when activists from over a dozen communities and neighborhoods across Boston joined together in attempt to capture the attention of newly appointed governor Francis Sargent.

The anti-highway protest came at a time when Americans around the country were collectively protesting several issues; activists in Boston were bolstered by their experience fighting in civil rights, black power, antiwar, and women’s rights movements. The protest was spearheaded by several figures—one of whom was Chuck Turner, a co-chairman of the Boston Black United Front as well as the Boston Committee on the Transportation Crisis. These served as umbrella organizations that unified protesters across several communities to collectively fight against the development of the highway system throughout Boston.

“There’s a moment in the black nationalist discussion where planning and highway construction become central to the identity of [these organizations],” said Dr. Crockett, who emphasized just how intertwined the anti-highway movement was with civil rights and black nationalist movements.

The movement brought together a diverse array of residents who came from backgrounds of all race, gender, and class. Their goal was to sway Governor Sargent to abandon the highway plans, an enormous feat considering Sargent had previously been commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Public Works and had played an integral role in previous highway development.

But their intense, passionate efforts paid off: Governor Sargent petitioned for funding in Washington to further develop Boston’s mass transit system, resulting in the extension of several MBTA rail lines. The Orange Line, which stretches from Back Bay through Forest Hills, now operates along the Southwest Corridor: the intended site for the I-95. At Roxbury Crossing, a bustling center through which thousands of diverse Bostonians traverse, a plaque commemorates the efforts made by citizens to halt the construction of the interstate.

The plaque reads: “You are standing in the middle of the Southwest Corridor. It was originally planned as the twelve-lane highway shown in the drawing below. The efforts of thousands of citizens banding together to save their homes, neighborhoods and open spaces created the Orange Line rapid transit, the railroad, and the Southwest Corridor Park you are enjoying today.”

Moving forward, Dr. Crockett indicated that urban development and infrastructure are still ripe topics in Boston city planning. Several parcels of land that were spared of highway development have recently been slated for new development, and Dr. Crockett fears that the initial intent for the land has been lost over the years.

“The original impetus was to halt this interstate highway expansion and to create employment and housing opportunities for those who need them,” said Crockett. “It wasn’t just about stopping the highway, but [was also] a new vision for city planning.”

Now, her main concern is evaluating who has benefitted from the development of the Southwest Corridor and other neighborhoods; she fears that urban developers have only hastened gentrification. Dr. Crockett’s inquiry into the movements that emerged in Boston and across the country in the ‘50s and ‘60s is still startlingly relevant, particularly at a heated moment in U.S. history. With several social, political, economical, and environmental issues at stake in the country, grassroots organizing is becoming an increasingly significant opportunity for Americans to evoke change; they need not look further than Dr. Crockett’s People Before Highways to gain insight into the successful execution of collective activism and community organizing.