The State of Global Climate Policy in 2024 and the Road to Baku and Beyond

By Jonathan M. Harris

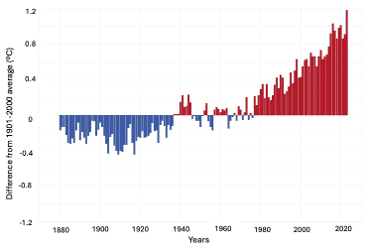

The year 2023 was the hottest year in recorded history, and 2024 is on track to be even hotter. Record high temperatures have been observed on land, in the oceans and in Antarctica. Global concentrations of major greenhouse gases climbed to their highest levels ever. Huge losses of ice were recorded in Greenland and from glaciers worldwide, continuing and accelerating a steady trend of increasing global temperatures since the 1960s, as seen in Figure 1.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the United States experienced “28 weather and climate disasters in 2023, surpassing the previous record of 22 in 2020, tallying a price tag of at least $92.9 billion.” Worldwide, extreme weather events included intensified hurricanes, unprecedented wildfires and deadly flooding in Greece, Turkey, Bulgaria, Libya and elsewhere.

Figure 1: Global Average Surface Temperature, 1880-2023

In this context of intensified climate crisis, the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) convened in November 2023 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. This was followed by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference in Bonn, Germany in June 2024, which involved “two weeks of intensive work across a range of issues where progress is needed on the path to the UN Climate Change Conference (COP29) this November in Baku, Azerbaijan.”

What are the prospects for global climate policy and the road to Baku and beyond? Amid a flurry of conferences and convenings, there has been some incremental progress in the global fight against climate change, but much remains to be done in the critical months and years ahead.

Global “stock take” on climate policy

The goal of these conferences is to evaluate and strengthen global responses to climate change, aiming to hold global temperature increase to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels—a level that was closely approached in 2023. This objective was set out at COP21 and in the Paris Agreement, and made more specific and ambitious at the 2021 COP26 conference in Glasgow, UK.

COP28 included a Global Stock Take (GST), representing a mid-term review of progress that UN member states were making towards the 2015 Paris Agreement (aiming at limiting temperature increases to below 2°C, with a more ambitious goal of 1.5°C).

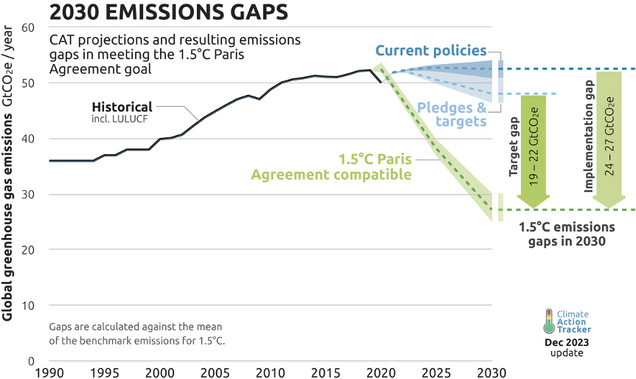

According to an analysis of the GST by the World Economic Forum, “global emissions continue to rise by 1.5 percent a year, when they need to reduce by 7 percent annually. The GST was a sobering reminder that the world was far off its targets.” The independent Climate Action Tracker finds that, even if all COP28 pledges and targets are met, the world will be well short of a “1.5°C Paris Agreement compatible” path of emissions reduction, leaving a significant “emissions gap,” as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Pledges, Targets and Emissions Gaps

Goals set at COP28

A principle that was accepted at COP28 is the need for net zero emissions by 2050. While this may seem far-fetched in the context of still-increasing global emissions, it has become a widespread basis for climate policy for many countries, communities and corporations. Intermediate goals that were accepted at COP28 included:

- Tripling the global capacity of renewable energy and doubling the annual rate of energy efficiency improvements before 2030.

- Rapidly phasing down “unabated” coal use. (The use of the term “unabated” implies the possibility of balancing emissions with carbon capture and storage—an as-yet unproven technology which has been criticized as simply providing an excuse for avoiding emissions reduction.)

- Significantly curbing non-carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, with a goal of a 30% cut below 2020 levels of methane emissions by 2030, including a 60% cut in methane emissions from the fossil fuel sector. Methane is a greenhouse gas that is shorter lived than carbon dioxide, but 80 times more damaging in terms of warming effects in the short run.

- “Phasing out” subsidies for fossil fuels “that do not address energy poverty or facilitate just transitions”–allowing some leeway for developing countries in particular to continue to subsidize fossil fuels.

- Transitioning away from fossil fuels to achieve net zero by 2050.

What will it take to achieve net zero?

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), implementation of the energy-related pledges made at COP28, including on renewables, efficiency and methane, would lead to a decline of about four metric gigatons (Gt) of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, relative to earlier projections. But the IEA also finds that this is only around 30 percent of the emissions reduction needed to keep the world on a path to limiting warming to 1.5°C.

Despite the conference statement that countries need to “transition away” from fossil fuels, critics noted that the resolution was “riddled with loopholes and lacks clear goals and fixed timelines.”

COP29 in November 2024 will need to do better. Its location and host in the petrostate Azerbaijan have led observers to be pessimistic about outcomes. The Bonn Conference in June 2024 aimed to smooth the path to more ambitious agreements at COP29. “We’ve taken modest steps forward here in Bonn,” said UN Climate Change Executive Secretary Simon Stiell in his closing speech. “[But] too many items are still on the table . . . We’ve left ourselves with a very steep mountain to climb to achieve ambitious outcomes in Baku.”

Agriculture, forests and natural systems

An important aspect of the net zero goal is the role of agriculture, forests and natural systems. Food systems now account for about 30 percent of global emissions. The Emirates Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems and Climate Action, with the support of 134 countries (representing 70 percent of the world’s land) pledged to include emissions from agriculture and farming in national climate action plans, aiming for a shift to sustainably produced and low-emission agricultural systems. But specific plans to transform world agriculture from a net emitter to a net absorber of carbon—theoretically possible given the great carbon absorption capacities of soils—were lacking.

Ending deforestation and preventing destruction of wetlands and other natural systems is an essential element for limiting global temperature increase. According to the World Resources Institute, COP28 saw some important but largely unheralded progress in this area. Progress has also been made on the $12 billion Global Forest Finance Pledge agreed at COP26 in 2021, with $5.7 billion, or 47 percent of the total promised finance, has already been directed toward forest-related programs in developing countries.

Financing climate policy

According to McKinsey Sustainability, “COP28 saw more than $80 billion in climate finance commitments. This level of financing is below what is needed, but there are real opportunities for this committed investment to spur additional financing.”

COP28 negotiations also resulted in an agreement to implement a Loss and Damage Fund, which will direct funding toward countries most vulnerable to the effects of extreme weather events, including droughts, flooding and rising seas. The fund raised almost $800 million during COP28. But the amounts raised pale in comparison with estimates of annual damages from climate disasters in vulnerable countries, which are in the range of $800 billion annually.

Conclusion: The road to Baku and beyond

Some recent developments are encouraging. Recent years have seen record-breaking solar output, with the IEA projecting that “more than 440 gigawatts of renewable energy would be added in 2023, more than the entire installed power capacity of Germany and Spain together. China, Europe and the US each set solar installation records for a single year, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IEA).”

Concomitantly, global greenhouse emissions continue to increase. China, the world’s largest current emitter, increased emissions by 10 percent between 2019-2023. China is heavily dependent on coal and has six times as many coal plants under construction as the rest of the world combined. Overall global emissions fell sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic, but have since bounced back, although the rate of increase has slowed. The IEA finds that “clean energy growth has limited the rise in global emissions, with 2023 registering an increase of 1.1 percent.” Other studies present an even lower estimate of only 0.1 percent for the 2023 increase.

A major medium-term benefit could come from the reduction of methane emissions. But strong policy action is needed to achieve COP28’s stated goal of near-zero methane emissions by 2030. The US Environmental Protection Agency, for example, has announced a methane reduction plan including methane emissions fees and technical assistance for a transition to no- and low-emitting oil and gas technologies. These and similar plans in other countries represent a start on harvesting this “low-hanging fruit” of unnecessary methane leaks and flaring, but much more needs to be done.

Perhaps the greatest achievement leading up to and following COP28 has been to change the framework for climate action to a more ambitious one, which is reflected in many national policies. The United States Inflation Reduction Act, for example, includes unprecedented incentives for a transition to renewable energy, many of which are just beginning to be implemented.

State and local net zero action in the US, and the acceptance of net zero as a policy goal in many countries and industries, represents a major turnaround. In early 2024, California hit a new record of generating 100 percent of its power from renewable sources for at least part of each day during a 100-day period in spring and summer 2024. California is ahead of many other regions, but the trend is clearly toward rapid expansion of renewables, with other states also setting ambitious goals for solar, onshore and offshore wind, and geothermal systems.

But many daunting barriers remain. Political opposition to climate policies, such as resistance by European farmers to agricultural emissions reduction plans, and broader opposition by the fossil fuel industry and other vested interests, are significant. The urgent need for rapid grid expansion to accommodate wind and solar has also engendered opposition, and grid upgrading requires major investment that may be difficult to mobilize. But at least the goal of net zero is now on the agenda, and progress will be measured at the next international conferences, COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan in November 2024, and COP30 in Brazil in 2025.

*

Never miss an update: Subscribe to the Economics in Context newsletter.