COP27 and Climate Policy: the Role of Agriculture, Forests and Ecosystems

By Jonathan Harris and Anne-Marie Codur

The United Nations Climate Change Conference known as COP27 took place in Sharm-El-Sheik, Egypt, this November. Opinions differ on whether the conference should be rated a success or a failure, but there were both some clear accomplishments and some important tasks for the future.

The urgency of effective action on climate issues was evident in 2022, as an unprecedented series of extreme weather events and disasters affected almost all regions of the planet. Heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, floods and hurricanes have made extreme weather a part of everyday life. Pakistan suffered massive disruptions as more than a third of the country was submerged in record flooding, and many other places including China, Europe and the US experienced extreme heat and drought affecting millions.

In this context, the results of COP27 may seem inadequate, but a specific item of progress was agreement on a “loss and damage” fund to compensate lower-income countries for damages from climate change. The deal was widely seen as a triumph, but countries have reported feeling pressured to forgo tougher commitments for limiting global warming in order to get the fund approved.

Agriculture, forests and natural systems are crucial to achieving climate goals

The role of agriculture in climate change received unprecedented attention at COP27, and featured in the “cover decision” along with forests and other natural systems. Reforming agriculture and food systems – currently responsible for one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions – will be essential to achieving the global goal of limiting warming to below 1.5 degrees.

Protecting the capacity of the global food system to feed a growing population requires improving the resilience of food systems to inevitable climate impacts. At the same time, there is enormous potential for carbon storage through regenerative agricultural systems and the promotion of such systems must be a key part of climate policy.

The role of ecosystem renovation in filling the climate policy gap

At the 2021 COP26 conference in Glasgow, UK, countries committed to strengthening their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), or pledges to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But results so far are limited, and well short of what is needed to limit the global temperature increase to 1.5°C, or even 2°C. According to the independent Climate Action Tracker, only a few countries are in the category of “almost sufficient”, while most are rated “insufficient” or “highly insufficient.” Clearly, faster reduction of emissions is essential. But even if this is achieved, it is very unlikely that the global goals will be met without a significant increase in carbon absorption by natural systems. COP27 failed to achieve significant strengthening of the NDCs, leaving a major gap between current pledges and needed reductions.

Good and bad news

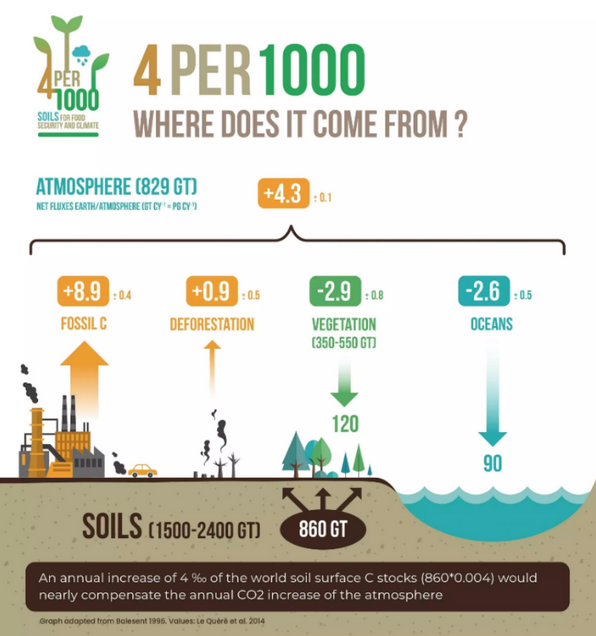

The good news is that the potential for carbon absorption by agricultural soils, wetlands and forests is very large. Global vegetation currently acts as a carbon sink, absorbing about 2.9 Gigatons (Gt, or billion tons) per year. The world’s soils currently store more carbon than the atmosphere, and the top layer of soils contains about 860 Gt of carbon. According to the International “4 per 1000” Initiative, an independent effort linked to the COP process, increasing this soil carbon storage by four-tenths of one percent per year (0.004) would store about an additional 3.4 Gt annually, almost completely offsetting current excess carbon emissions of 4.3 Gt per year, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Planetary Carbon Flows

At the same time, according to scientific studies, promoting additional carbon storage in existing forests and wetlands by preventing deforestation, allowing current second-growth forests to reach maturity and restoring degraded and deforested lands could store up to an additional 5 Gt of carbon per year. In theory, achieving these goals, together with reducing current industrial emissions, could result in negative annual carbon emissions, reducing the total level of atmospheric carbon accumulations over time.

The not-so-good news is that the world is very far from achieving these carbon storage levels. Currently, agriculture is a major source, not sink, for emissions, accounting for about 18 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions. Global forests are being lost at a rate of about 10 million hectares per year.

Some efforts have begun as part of the COP process to reverse these trends. The Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture, adopted at COP23 in 2017, recognizes the unique potential of agriculture in tackling climate change and seeks to “mainstream agriculture into the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCCC) process.” COP27 reaffirmed the importance of the Koronivia process, renewing it for another four years. According to Mamadou Goita, Director of the Institute for Research and Promotion of Alternatives in Development:

“The industrial food system is responsible for over a third of global warming emissions – and now finally the UN climate talks are recognizing that. It’s a significant step to see that the UN climate agreement will begin to target greater action to tackle the enormous emissions from industrial agriculture and provide funding to make agriculture more resilient to climate change. But if actions are not incorporated across the whole food system, from food waste and loss to sustainable supply chains and healthy diets, we will fail to meet the world’s great food and climate challenges.”

At COP26, the Glasgow Declaration on Forests and Land Use, signed by 100 countries representing 85 percent of the world’s forested land, pledged to end deforestation by 2030. In a separate pledge for global forest finance, 12 countries, including the US and EU, promised to provide $12 billion for forest-related climate finance between 2021-2025.

But implementation again is the sticking point. COP27 expanded the Glasgow commitments with a pledge by a group of 26 countries representing a third of the world’s forests to “track commitments” on efforts to “halt and reverse forest loss by 2030.” Major forested countries, however, declined to join this new pledge, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Brazil, Russia, China and Peru, which together account for nearly half of the world’s forests. This leaves effective implementation of forests preservation pledges in doubt.

Natural systems are key to successful climate policy

The outcome of COP27, while indicating some progress on” loss and damage”, and is not promising. given the failure to strengthen the already declared country commitments to greenhouse gas emissions reduction. The conference decisions included greater prominence for natural solutions including soils, forests and wetlands, but it is essential for participating countries to move beyond broad statements to specific policies that maximize carbon storage in agricultural soils and natural ecosystems.

*

Never miss an update: Sign up to receive the Economics in Context Initiative newsletter.