Data analyst from Boston Cyclists Union offers strategy to better assess transit equity

On June 21, Raphael Dumas, a Mapping and Data Analyst at the Boston Cyclists Union, visited BU City Planning and Urban Affairs (BUCPUA) students in Doug Johnson’s UA 510 Course, Transit-Oriented Development in the 21st Century. Dumas provided research insights from his master’s thesis on analyzing transit equity using automatically collected data.

“We hear a lot of complaints about the MBTA system in how it functions, its reliability, and its constant issues with consistent service. However, what we don’t hear as much about is the spatial mismatch created by areas that are not well serviced by the MBTA, leaving several neighborhoods around Boston with an immense challenge of getting access to employment opportunities. In his thesis, Raphael was able to investigate these issues more closely and walk us through a rational approach to understanding how and why they happen, and how we as planners should be addressing policy and research implications for the future of these areas so that they can receive better access to transit and job opportunities,” shared Jeannine Stover (MET’16), a master of city planning candidate.

Throughout his lecture, Dumas chronicled legal mechanisms aimed to reinforce transportation equity, such as the Urban Mass Transportation Assistance Act of 1970 and the Federal Transit Act of 1998 (Title III of the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA 21)). In 1994, President Clinton signed executive order 12898, “Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations”.

Support from these legal acts, however, did not diminish the prevalence of automobile-dependent, low-income areas, where sorely needed public transit is not accessible. As land values around transit-oriented areas increase, more residents are displaced or willingly move due to increased cost burdens. Additionally, each time public transit fares are increased, the Federal Transportation Administration must determine if there are disparate impacts upon race and disproportionate burdens upon income.

“Each passenger should be the unit of analysis that is measured to determine if public transit is actually achieving its equity and efficiency objectives,” shared Dumas. Using blocks or neighborhoods as the unit of measurement for equity analysis assumes the neighborhood or block populations are homogeneous, which is not often the case in Boston.

Dumas asserted that automatically collected data from Charlie Cards, including ID numbers, time stamps, and fare box IDs, can help researchers understand passengers’ journey preferences and modes. By applying if-then heuristics, researchers can infer journey patterns, such as overall travel times, number of travel segments, and identify peak density times at well-frequented MBTA stations.

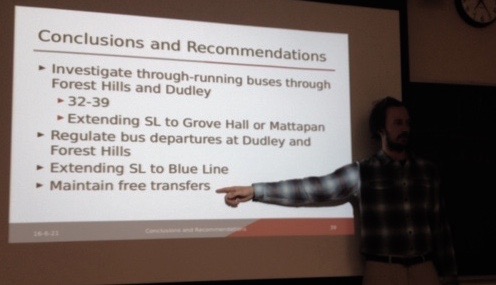

Dumas also stressed maintaining free transfers, especially as policymakers consider implementing transfer fees. Furthermore, he proffered that creating a light rail line along the MBTA Fairmont Commuter Rail branch could help alleviate spatial mismatch for nearby low-income residents. In 1987, the Elevated Orange Line was removed, but a better or equal public transit solution has yet to be fully realized for many of these residents.

In 2015, Dumas received his Master in City Planning and Master of Science in Transportation from the Massachusetts Institute for Technology. Dumas also holds a Bachelor of Engineering degree from McGill University. He previously served as a graduate teaching assistant at MIT and research assistant for the MIT Transit Research Group and Laboratório de Transporte de Cargo in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

– Courtney Thraen (MET’17)