Category: Summer 2014

Midsummer Mischief

By Julie Rattey | Photo by Christopher McKenzie

Forget the fairy wings. In the Classic Repertory Company (CRC) production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, costumes, lighting, and sets are nearly nonexistent. The jean-clad cast of eight (mostly CFA alums) remains onstage at all times, transitioning between roles and scenes to the beat of a drum. Midsummer is rife with transformation (of scorn to love, friend to foe, and, memorably, an average Joe into the donkey-headed paramour of a fairy queen) and the CRC’s minimalist aesthetic underscores this theme, inspiring actors and audience to refashion space through imagination.

“You come back to the basics—who are these people and what are they doing?” says Celia Pain (’13), who plays the mischievous sprite Puck and is education and advocacy coordinator for CRC, the flagship educational outreach program of the New Repertory Theatre (New Rep) in Watertown, Massachusetts. Pain and her fellow actors bring stage adaptations of classical and modern literature to New England-area schools and communities, including those underserved in the arts.

“Not only does our accessible approach to the material hopefully give them new insight into or love for these texts, but I think it’s really good for these kids to see that we went to school for something we are passionate about, that school can be fun,” she says.

CRC, which is in its first year of partnership with Boston University, is a bridge program that aims to help recent graduates make the leap into professional theater. “It builds their confidence, it builds their stamina, it builds their résumé,” says Jim Petosa, New Rep’s artistic director and the director of the College of Fine Arts School of Theatre, “and it gives them that important thing that an actor always needs: an audience to engage.”

Please Sit on the Art

By Lara Ehrlich and Laurel Homer | Photo by Kamen Kozarev

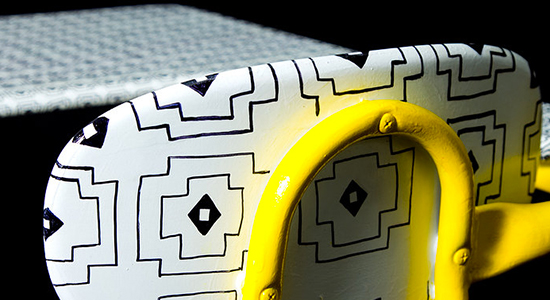

Hila Landesman (CAS’13) created the Chair Project, a site-specific installation that enlivens CAS classrooms one chair at a time. Photo by Kamen Kozarev

“Whoever painted this desk made my day!” a Boston University student posted on Instagram with the hashtag #thechairproject and a snapshot of a rainbow-hued desk. Hila Landesman (CAS’13) is the artist behind this desk chair—and 21 more, which together make up the Chair Project, a site-specific installation that enlivens CAS classrooms one chair at a time.

Landesman, an economics and environmental policy major, embraced her lifelong passion for the arts by enrolling in CFA Professor Hugh O’Donnell’s site-specific design course during her senior year at BU.

“I wanted to be around different people with different interests and backgrounds,” she says. “The word ‘interdisciplinary’ caught my eye in the course description. Sure enough, the course was filled with students from various majors with different ideas and goals. It was very exciting.”

Inspired by the class, Landesman enlisted artists from CFA, CAS, COM, and SMG to paint the chairs, which students now use in every type of class, from art history to land use planning to Hindi. Students share their love for the chairs on Twitter and Instagram, and vie for the chance to sit on Landesman’s site-specific seats.

The Chair Project

Esprit talked with Landesman about her chair-painting process.

You enlisted the help of other students from a variety of majors and schools. Tell us about working with them.

It was inspiring. I loved seeing the ideas that each artist came up with and observing each artist’s process. I started out by asking two other students in site-specific design, both business majors, followed by two students in the sculpture studio course I was taking. After that, I was given a studio in the painting wing of CFA, where I was surrounded by talented painters whom I approached based on the work I saw in their studios. I also enlisted one student from site-specific design the following semester. Two of the artists are my very talented friends from outside of BU, and two other artists are my sisters, the younger of whom is 11.

What has been your favorite reaction to the chairs?

My favorite reaction so far actually came from the night-shift facilities crew when I was installing the project. They were so excited to see the chairs and were hoping this would be the first wave of many chairs to come. These chairs made their night of cleaning and organizing classrooms so much more exciting. One of the women told me, “There should be at least four chairs in every class!”

What was your greatest challenge?

The biggest challenge by far was finding motivation to see the project through to the end, despite what was happening in my life. Having great ideas and big visions is easy; actually finishing what you start takes a lot of discipline.

What surprised you the most about the project?

I was advised to test all my materials before using them, but I didn’t realize how very crucial that advice was. Knowing your materials—and a little bit of chemistry—is really, really important. For example, did you know what polyacrylic makes Sharpie marker run because Sharpie is alcohol-based? Well, now you do!

How has the Chair Project transcended art and become a metaphor for cross-disciplinary collaboration?

I have situations where my desire to connect two different interests or fields was met with resistance. For example, I’ve heard comments like, “Why are you studying environmental policy? That’s the opposite of economics.” I want to dispel the notion that one field of study is better than or at odds with another. Every field must use the knowledge acquired by those in other fields to advance and develop. Collaboration and communication across departments and schools should be the norm, not the exception, and I hope that the Chair Project can help start conversations about ways to increase teamwork and partnerships at BU.

How did the site-specific design course and the Chair Project impact your experience as an undergrad?

Taking site-specific design during my last semester at BU was perfect for me because it tied together so many different themes and gave me an opportunity to meet people I wouldn’t have met otherwise. I definitely feel more connected to BU now and more invested in the improvement of students’ learning experiences.

Do you have a favorite chair?

I’ll tell you about the first chair of the project, which I made. It’s the white chair with the yellow, blue, and red legs. The designs on that chair are my signature doodles, which filled my school notebooks for years. If you look closely, I always embed words into the designs. One thing I wrote on this chair is, “What are you having for lunch?”

What would you tell someone thinking of taking a course outside their primary discipline?

Do it! After college, everything you do is interdisciplinary. Get ahead and start now.

Witnessing Reality

For activist and composer Matt Gould, theater is about philanthropy—and transformation

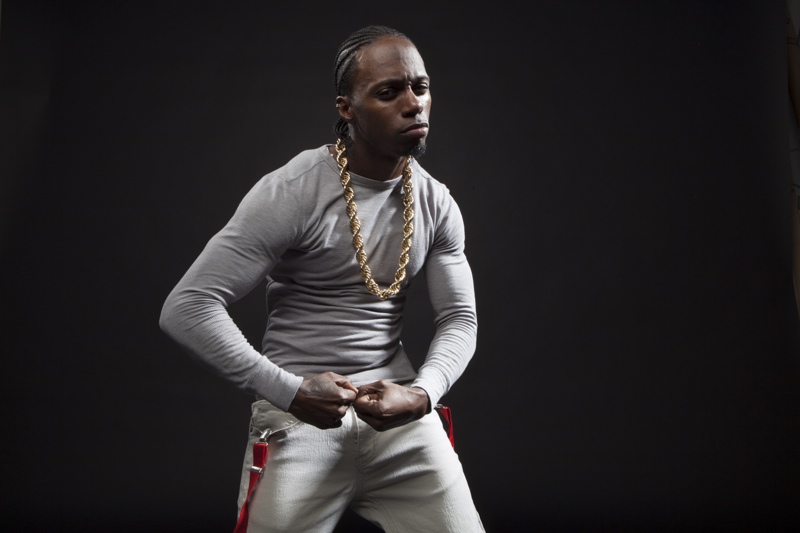

By Suki Casanave | Photo of Matt Gould (’01) and Griffin Matthews by Daniel Kim

In the basement of the American Repertory Theater, Matt Gould (’01) is pulling on his favorite leather boots—the ones with the soles that can really hammer out the sound when he’s onstage. Outside, the February night in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is bitterly cold, with windchills pushing temperatures into the single digits. But in Gould’s tiny, brightly lit dressing room, the radiators are on overdrive. Unfazed by the stifling heat, he leans against the cinder block wall philosophizing about the dangers of success, about staying true to your ideals. He has already done his breathing exercises, and—his other preperformance ritual—lit a candle, which flickers in the corner. Now, dressed in black jeans, black waffle-knit shirt, and black-rimmed glasses, he’s pretty much ready to go. Except for his boots, which he finishes lacing and knotting—and then it’s time.

Matt Gould (’01) and Griffin Matthews created the musical Witness Uganda, inspired by their struggle to help Ugandan orphans afford an education. Photo by Daniel Kim

Minutes later, Gould is sitting at a keyboard, stage right, head bobbing, arms waving, feet stamping, casting a musical spell that surges through the theater. The stage explodes with the rhythms of Africa, as dancers in traditional dress whirl past in a blur of color. Nearly invisible in the shadows, Gould is a frenzy of energy as he leads a seven-piece band, his hands punctuating the darkness with musical directions, his face joyous.

Dubbed by its creators as “the world’s first documentary musical,” Witness Uganda started with a quest for meaning. “I was searching for my cause,” says Gould, who headed into the Peace Corps as soon as he graduated from CFA’s School of Theatre. He spent two years in Mauritania, where he produced Romeo and Juliet with a group of teen girls—but was overwhelmed by the AIDS problem he’d hoped to help solve. Gould returned to the United States completely discouraged. “I thought I’d go there and change the world,” he says. Instead, his idealism was nearly snuffed out. “For several years, I wandered around in New York City and Los Angeles trying to turn my African experience into something artistic.”

The stage at the American Repertory Theater explodes with the rhythms of Africa. Photo by Gretjenhelenephotography.com

Meanwhile, in Pennsylvania another young artist, Griffin Matthews, was also struggling to find his way. Worn out by an endless search for acting jobs and banned from his church choir because he is gay, Matthews, a musical theater major from Carnegie Mellon, left home in 2005 to volunteer in Uganda. While he was there, he was befriended by a group of street orphans, most of whom had lost their parents to AIDS. The kids could not afford to attend school, and begged Matthews to be their teacher. And so, for a few weeks in a makeshift classroom in a vacant building, that’s exactly what he did. When he returned to the United States, determined to continue helping “his kids,” Matthews founded the Uganda Project, a nonprofit devoted to providing the one thing the orphans desperately wanted, but could never achieve by themselves: an education. Matthews raised enough money to enroll the kids in school, and stayed in touch, helping with food, books, clothes, and ongoing tuition. He visited Uganda once a year and talked to the kids constantly on email, Skype, and Facebook.

“Matt wants people to feel things, to have a heartfelt, moving experience in the theater. He’s also one of the most talented people I know—the world needs to experience his music.”—Nicolette Robinson, cast member

But in 2008, when he met Gould, Matthews was in a panic. The economy was crashing and Uganda Project expenses had doubled, from $25,000 to $50,000, as some of the students started enrolling in college. One night, as Matthews was venting about how hopeless he felt, Gould began recording. He added music to Matthews’s monologue, and an idea was born: theater as philanthropy. Why not create a fundraising event, a sort of staged infomercial for the Uganda Project based on Matthews’s story? Their collaboration began with two sold-out shows in a rented theater—and made absolutely no money. But people responded. They cried. They came up and talked afterwards. “The story touched people,” Gould says. He wrote a few more songs. And a few more. Together, he and Matthews worked on a script.

In 2010, they were invited to present Witness Uganda at the ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) Musical Theatre Workshop directed by composer Stephen Schwartz, whose credits include Pippin, Wicked, and Godspell. The show was still evolving at the time, Gould explains. “But we knew what was at the heart of it—people wanting to help.” That same year, they also won ASCAP’s Michelle and Dean Kay Award and Harold Adamson Lyric Award. In 2012, they received the prestigious Richard Rodgers Award for Musical Theater—and American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) Director Diane Paulus took note. “I was knocked out by the score,” she says, “and by the subject of the story.” In the show’s program notes, Paulus describes Witness Uganda as “a new American musical . . . telling a story that you wouldn’t normally see told on stage.”

The production is shot through with emotion, with moments of soaring joy and searing disappointment—which is precisely what makes for good theater, according to Gould, who learned to love grappling with the range of human experience during his theater classes at BU. “My profs, many of whom are still at CFA, were interested in raw emotions, in things that were rough around the edges,” he says. “This is what makes theater feel alive and real.” Even his fellow students seemed to embody this philosophy, recalls Gould. “You could always spot a BU theater kid,” he says, laughing. “Our hair was always a little messy, our style was always a little rough.” And then he turns serious again. “It’s a thrilling quality, because it’s real. It’s what life is.” There are plenty of programs, he says, that teach you how to dress, how to nail the perfect audition, how to cut your hair and sculpt your body. “But BU taught me how to be an artist.”

One night, as Matthews was venting about how hopeless he felt, Gould began recording. He added music to Matthews’s monologue, and Witness Uganda was born. Video by Mariana Blanco

Gould is an artist on a mission, an artist devoted to working with life’s rough edges and making them beautiful. “I think all artists have a responsibility to be activists,” he says. “Our job is to dig around and tell the hardest, most painful version of the story we can find. If we haven’t fought to tell it, then it’s not worth telling.” For Gould and Matthews, that story began as a personal quest to do good that grew into something much bigger—musical theater as a message of hope and an exploration of meaning. “It’s about turning to someone else and asking, ‘How can I serve you?’” Gould says. “That’s really the beginning of healing, the recognition that there’s something more, something outside yourself.”

Gould’s music, a high-octane blend of African rhythms, gospel harmonies, and contemporary pop sounds—plus street calls delivered by Gould himself, head thrown back—carries the show from start to finish, with lyrics that take the audience along for an earnest exploration of the impulse to help and the challenge of creating real change. “What’s my place on this planet?” sings Matthews, early in his quest. Another song, “Bricks,” is about how much easier it is to raise money for structures than it is for something intangible, like education. But the Uganda Project isn’t about constructing buildings. “We resurrect people,” shouts the cast in one rousing number. In the end, Gould leaves the audience not with answers, but with a joyous directive: Bela musana. “Be the light.”

Matthews raised enough money to enroll the kids in school, and stayed in touch, helping with food, books, clothes, and ongoing tuition. Photo by Andrea Moore

The show has received positive reviews from the Boston Globe and the Huffington Post, among others, and typically brings the audience to its feet. As soon as the house lights come up, Gould and Matthews reappear on stage for “Act III” to answer questions. Sometimes they are joined by guests like Timothy Longman, an associate professor of political science and director of the African Studies Center at BU, who did some consulting on the production during its development. “What I love about the show,” he says, “is that it’s inspirational, but also self-effacing. It’s a nice critique of the sort of naïve approach to doing good in Africa.”

On this February night, someone in the audience asks whether Matthews and Gould plan on returning to Uganda, given the recent news. For a moment there is silence. Only hours earlier, the Ugandan government signed into law a bill criminalizing homosexuality and, in some cases, imposing life sentences. “We don’t know yet about returning—it’s scary and inhumane,” says Gould, noting that they’ve heard from people trying to flee the country. “They fear for their lives.”

“I think all artists have a responsibility to be activists. Our job is to dig around and tell the hardest, most painful version of the story we can find. If we haven’t fought to tell it, then it’s not worth telling.”

—Matt Gould

The conversation is a sobering reminder of harsh social and political realities. That’s the point of these post-performance “talk-backs,” says Gould. It’s a way to continue the dialogue on issues that deeply matter and touch the lives of real people. “There’s this pervasive idea that theater is escape—which may have been true at one time,” he says. But today, Gould notes, nearly everything we do is about escape. Theater, by contrast, should be the one place where we can’t escape—where we’re forced to “witness” reality. “We’re hoping people leave the show saying, ‘I lived fully for two hours, and now I have a new understanding of life and my role in it, a new understanding of what I need to do.’”

As the theater empties, Gould and Matthews greet people in the lobby, dispensing hugs and posing for pictures. Finally, after the last group of fans has offered its thanks, after every question has been answered and the very last person has turned to go, Gould makes his way back to his dressing room and changes his shoes. Then he heads out, humming, into the night.

How Art Helped Heal a City

In the wake of unthinkable tragedy, one CFA student proves that making art can deliver solace

By Lara Ehrlich | Photo by Conor Doherty

Iraq War veteran Evan Gildersleeve donated his piece Boston: Hope Lives On to the Boston Police Department. Photo by Evan Gildersleeve

While serving in the Marines Infantry Sniper Unit in Iraq, Evan Gildersleeve combatted the long stretches of boredom punctuated by indescribable violence the best way he knew how: He sketched his fellow marines, the city of Ramadi, and the Iraqi people “to document what I saw, and my emotions,” he says. “In one hand, I had a sketchpad; in the other, an M240 machine gun.”

Upon returning to the States, shell-shocked and suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, “I turned to painting my sentiments, because it was a way to visualize what I was up against.”

His recovery took a bewildering turn after the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, which echoed the violence he had experienced in Iraq and left him feeling adrift. “I have military skills, but I felt helpless because I couldn’t use them,” he says. Once again, he turned to the one skill he could use to help others, and to make sense of a world altered beyond recognition.

On a rainy spring afternoon, Gildersleeve and his wife, Petra, joined dozens of strangers at Boston University’s 808 Gallery to create art in honor of the first responders and bombing victims, including graduate student Lu Lingzi (GRS’13). This was the first “art marathon” event hosted by Still Running, a nonprofit effort founded by BU sophomore Taylor Mortell (’16) and alum Luca De Gaetano (’13). In the year following the tragedy, Still Running hosted a series of art marathons and community exhibitions, offering Boston citizens a conduit through which to help their wounded city heal and to give voice to the otherwise inexpressible.

An Art Marathon

Making art in response to tragedy was a natural impulse for Mortell. At 15, she had endured a traumatic brain injury and “having something to occupy my mind” had been instrumental to her recovery. “Art helped me feel productive, especially because I couldn’t do schoolwork. It felt good to be able to do something.”

After the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, members of the community took solace in art-making events hosted by Still Running, a nonprofit founded by Taylor Mortell (’16) and Luca De Gaetano (’13). Each participant had a story to tell. Photo by Taylor Mortell

A painting and sculpture major at CFA, Mortell creates contemplative oil portraits in earthy palettes, and the studio hours slip by as she surrenders to “the tactility and physicality of working the material. Making decisions about which colors to use and how to move the brush is a culmination of the mental concentration and the physical coordination of art-making. That’s when I am the most focused in mind and body.”

Mortell was inspired to launch Still Running, which is supported by grants from the BU Arts Initiative and Youth Service America, to give others the same opportunity to find focus and restoration through art. The idea resonated with her peers at BU, and she quickly attracted volunteers and advisers, including Hugh O'Donnell, professor of painting at CFA, and Jack McCarthy (GSM’02), an associate professor of organizational behavior at BU’s School of Management. McCarthy connected Mortell with local contacts that provided advertising support and financial assistance.

“Making decisions about which colors to use and how to move the brush is a culmination of the mental concentration and the physical coordination of art-making.”—Taylor Mortell

The art marathon events attracted a cross section of participants, including local artists like Gildersleeve, art students, community members, and curious passersby. “It was everybody,” Mortell says. “We got people ages 4 to 86; some said they didn’t know anything about making art,” but as they began to work, they realized something Mortell had discovered as a teen—the simple act of taking paint or crayon to a blank page can focus grief and deliver solace.

Painter Caitlin Serpico (’16), who donated several works to the project, says art helped her “release my feelings” about the tragedy. The glass depicted in her watercolor painting “shows signs of cracks and chips and yet it still retains water. I accompanied this image with a caption that states, ‘You may be cracked or chipped but that does not mean you cannot be filled.’”

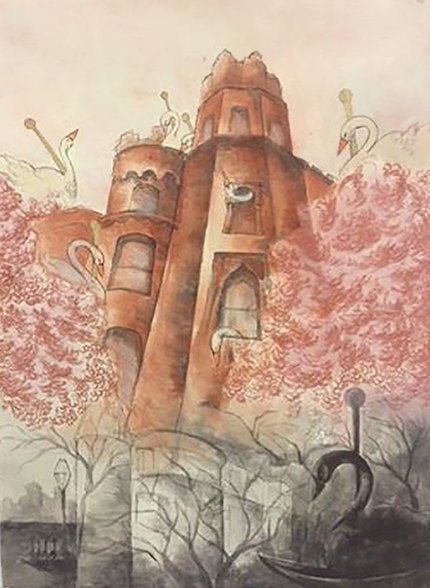

In a piece by Massachusetts College of Art and Design student Alyssa Aviles, a brownstone rises from black and white charcoal into soft pastels, populated by swans freed from their Swan Boats. “I am struck by the way in which the city overcomes the harsh, white winter and blooms into magnificence,” Aviles says in her artist’s statement. “In the same way that Boston defeats the bitter cold, it has conquered a heartbreaking tragedy with resilience. I took images that to me represent Boston and created a scene that depicts a transition from a static, colorless space into a place that is triumphant with life and color.”

“I enjoyed seeing how making art helped people deal with what happened in their city,” says Mortell’s former high school art teacher, Meghan Dinsmore (’04, ’05), who participated in a number of the art-making events and, for her donation, illustrated the bold letters B-O-S-T-O-N with shoelaces and the city skyline. She found that “each member of the community who participated in Still Running had their own story to tell and dealt with their emotions in their own way.”

From Pasta to Paint

Alyssa Aviles drew inspiration from Boston’s landscape for her Still Running piece. Photo by Alyssa Aviles

The arts tap into our psyches, providing a channel through which to express our emotions, says Nancy Lowenstein (SAR’87), clinical associate professor of occupational therapy at BU’s College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College and a former art therapist. Crisis centers, hospitals, and rehabilitation facilities use art therapy to help patients heal from trauma; the process of selecting colors, shapes, and forms promotes healing. Different media helps people get at different emotions, Lowenstein says. Smashing clay might help one artist release tension and anger, while blending pastels might help another artist attain serenity. “People will find the media that works well for them, in terms of getting to those emotions and feelings.”

When Mortell was recovering from her brain injury, she worked in pasta. It may sound silly, she says with an embarrassed laugh, but cutting the spaghetti and arranging the pieces into flowers and robots was “soothing.” The process occupied her hands and alleviated her restlessness, until she was able to focus on more complex projects, like a self-portrait in tempera paint.

Artists also find that different tools help them express different emotions, as Gildersleeve discovered while creating his Military Experience in Oil Paintings series. “I used a palette knife to get out the feeling of what I experienced in Iraq,” he says. “It’s an aggressive tool that artists can use to attack the canvas, as opposed to making it refined and beautiful. It’s an emotional way to converse with the painting. A brush is a finer tool used for adding detail. It was a while before I was able to pick up a brush.”

“The artistic process helps people who feel helpless.”—Evan Gildersleeve

Lowenstein adds that the Still Running art marathon events were particularly effective not only because the participants were making art—but because they were making it together. “There are a lot of benefits to the pop-up art projects,” Lowenstein says. “When you’re in a group, you’re talking to people, sharing your experiences, and sharing your art. A lot of healing goes on.”

Though the art marathons were originally intended as sprints—just three weeks—they grew beyond Mortell’s expectations into a yearlong effort, with monthly community events hosted at locations throughout Boston. At each event, Gildersleeve says, “There were a lot of bright spirits and good energy, and it felt like we were able to do something. The artistic process helps people who feel helpless.”

Hope Lives On

Caitlin Serpico accompanied her Still Running piece with the caption “You may be cracked or chipped but that does not mean you cannot be filled.” Photo by Caitlin Serpico

Two weeks before the 2014 Boston Marathon, CFA hosted the final Still Running exhibition at the Boston Symphony Orchestra, where Dean Benjamín Juárez lauded the community artwork as “an expression of the feelings and emotions of those touched by what happened a year ago in Boston.” He presented Mortell with the 2014 Citizen Artist Award in recognition of her role as an advocate for art that serves as a positive force for enlightenment, change, and compassion. Mortell accepted the microphone to donate the Still Running artworks to first responders, members of the armed forces, marathon runners, the Boston police, and the family of Lu Lingzi.

Straight-shouldered in a suit with a Marine Corps eagle tie clip, Gildersleeve clapped for Mortell from the back corner of the room. His PTSD can be triggered by crowds. Still, when Mortell invited him to the podium, he navigated through the assembly to present his oil painting, Boston: Hope Lives On, to Superintendent-in-Chief William Gross of the Boston Police Department. The painting of a winged red cross surging up through blue and yellow swirls now hangs at the police headquarters.

“With each blast my heart perished, yet was saved by the selfless acts of the citizens of Boston that came to the aid of their fellow man,” Gildersleeve says in his artist’s statement. “Their selfless acts gave me hope. Disregarding their own well-being, they risked life and limb to save the hopes, dreams, and lives of all who watched.” Creating the painting allowed Gildersleeve to express his feelings about the tragedy, and donating it to Still Running allowed him to “end this helpless feeling inside.”

Additional reporting by Susan Seligson.

Homepage illustration by Nirlay Kundu.

So You Think You Can Dance…to Mozart?

By Lara Ehrlich | Photo by Cydney Scott

It was too loud for conversation at the Barking Spider Tavern in Cleveland, Ohio, an intimate venue where an eclectic mix of live folk, rock, blues, bluegrass, jazz, reggae, and gospel spills out into the beer garden on any given night. Courtney Miller (’16) had left her friends to squeeze through the tables for a jam session with classical musicians from the nearby Cleveland Institute of Music, where she earned a master's degree. She fitted the reed into her oboe, and leaned into the haunting first notes of Bach’s Oboe Sonata in G minor. The crowd quieted beneath the swaying Christmas lights and Miller felt good—until she returned to her table, where her friends told her the performance had made them uncomfortable.

At CFA, Courtney Miller (’16) found company navigating the challenges of a classical music career. Photo by Conor Doherty

“Why?” she asked, mystified.

“You were playing Bach,” they explained. “We should be at a concert hall. We feel guilty for sitting here in jeans, drinking beer.”

Their reaction stunned Miller. “It resonated with me so much that they had a preconceived idea of classical music—even though they are my good friends and they know I’m a goofball,” she says. “They thought what I did for a living was totally inaccessible.” If her oboe intimidated even her closest friends, how could she hope to reach a broader audience?

This question hounded Miller all the way from Cleveland to Boston, where she is a doctoral student at the School of Music. At CFA, Miller found she wasn’t the only one asking questions about building an audience and navigating the challenges of a classical music career. In 2013, the School brought together industry experts, musicians, educators, scholars, and composers for the Are We Listening? symposium, which addressed the question: How can we find ways to innovate while retaining the core standards of our field? Here are just a few ways students and alums are answering this question in their work.

Taking the Music Off the Stage

In her quest to introduce the oboe to new audiences, Miller turned to another musical genre for inspiration. “Pop musicians have been making music videos for decades, and we don’t even stick our toes in it,” she says. Miller and fellow musician Ceylon Mitchell (’13, ’14) wondered if they could apply the music video model to the classics, and they hit the Boston streets with an oboe and a video camera to find out. When the video of Miller performing Clara Schumann’s Romance No. 2, Opus 22 in her favorite locations around BU reached 800 hits, the duo knew they were onto something.

For the next video, Miller reached out to self-taught hip-hop dancer and Boston native Ernest “Eknock” Phillips, whose work she had admired on the hit television show So You Think You Can Dance. Though Phillips didn’t share Miller’s background in classical music, he was intrigued, and they decided to collaborate on Mozart’s dreamy Oboe Quartet K. 370, Movement II Adagio.

Hip-hop dancer Ernest “Eknock” Phillips improvises to Courtney Miller's oboe performance of Mozart. Video by Ceylon Mitchell (’13, ’14)

Phillips was drawn to the Adagio because “I talk fast; I dance fast. So my challenge was slowing it down so people can see my moves. I had to make everything tighter, cleaner, and less aggressive. Slow music brings out the whole emotion of the moment.” In the video, Phillips improvises to Miller’s oboe in the Boston Common and Public Garden, matching his moonwalk to the oboe’s plaintive pace.

Marrying the styles was equally demanding for Miller; her greatest challenge was staying true to the music. Though her mother suggested adding hip-hop beats to Mozart, Miller believes “in the absolute integrity of the music. I’ve spent the last decade of my life studying the oboe and trying to do it justice. My side of this collaboration is to evangelize the music.”

She is equally adamant that her videos should not dumb down the music, but instead emphasize elements that would engage even the least musical audiences. For instance, when listening to the Adagio for the first time, audiences might not pick up on Mozart’s humor, Miller says, so in one scene, she and Phillips played a flirtatious game of hide-and-seek to highlight “the joy and the mischief” of the piece.

Miller intends for her videos to intrigue audiences who might otherwise find classical music inaccessible—and it’s working. She now has viewers as far-flung as Kenya and Portugal and Saudi Arabia. “It’s really cool,” she says, “and something I couldn’t do just from the stage.”

Saying “Yes” to Strange

Opera composer David T. Little’s newest work began with a feeling he couldn’t articulate, “kind of like staring at white lines on a TV. You start to see things in it if you stare long enough.” He turned to his longtime collaborator and producer, Beth Morrison (’94), to bring the feeling into focus.

“I helped David articulate the idea in a way that allowed him to feel safe to explore it,” Morrison says. With all of her collaborators, she wants to “see how deep and how strange an idea can go, and where it might take us. I try to support the scariness of going out on a limb and trying something new.”

Creative Producer Beth Morrison (’94) collaborates with composers to develop new works like David T. Little and Royce Vavrek's black comedy, Dog Days. Video by BMP

Morrison knows all about trying something new. She initially studied to be a vocal performer, earning a bachelor’s in music from CFA and a master’s in music from Arizona State University, but she never felt comfortable in the spotlight. It was only when she became the administrative director of the Boston University Tanglewood Institute that she realized what she was meant to be doing—and it changed the course of her career. “It was exciting to create a vision for a whole institute,” she says. “As a performer, the focus is really so much on yourself. Once I was able to focus outside of myself, I was in a much more fulfilled position.”

Morrison founded the indie opera company Beth Morrison Projects (BMP) in 2006, and in less than 10 years, she has become one of the most sought-after producers in the opera world. BMP champions music-theatre, opera-theatre, and multimedia concert works by today’s most exciting emerging artists, like Little and Missy Mazzoli (’02), whose opera Song from the Uproar was featured in the Summer 2013 issue of Esprit, and is now touring.

In less than 10 years, Beth Morrison has become one of the most sought-after producers in the opera world. Photo courtesy of BMP

These daring new artists—as well as established composers like David Lang, Tod Machover, and Philip Glass—are drawn to Morrison because she is doing something new. Some traditional opera companies develop work, some produce work, and others do both. BMP does more.

As creative producer, Morrison collaborates with composers to develop new works, unbridled by the limitations of bigger organizations. She assembles the creative team; secures the world premiere venue, funding, marketing, and publicity; and develops the pitch materials—all the components that must come together in order to create a new work. For Little’s piece, Artaud in the Black Lodge, for instance, “we are just at the beginning of dreaming up what the project is, who the collaborators will be, and where we will premiere the work. It’s an exciting place to be, because anything is possible.” The production elements reinforce the collaborative atmosphere Morrison cultivates for her team, allowing them the freedom they need to innovate and push boundaries.

"The greatest work happens when people feel they can experiment," says Beth Morrison. Photo by James Daniel

For Morrison, success comes back to this freedom to innovate. “I never say to a composer, ‘You can’t use electronics, or you can’t have more than five players’—the kind of limitations that are put upon composers by commissioning organizations and larger institutions. The greatest work happens when people feel they can experiment.” Her collaborators respond by producing works that are like nothing else in the opera world. For an ambitious new artist, Little says, “the most important thing is having someone who says ‘yes.’”

Establishing Your Own Style

Kendall Ramseur (’12) was home for the holidays during his final year in graduate school at CFA, when he received a phone call from a concerned family friend: How would he support himself as a professional cellist? How would he pay off his student loans? How would he live? The well-meaning friend urged Ramseur to give up his lifelong dream and join the Air Force.

By the time he arrived at CFA, Kendall Ramseur (’12) had performed for Maya Angelou, accompanied the American Ballet Theatre, and played with the Grammy Awards Orchestra. Photo by Shef Reynolds

Ramseur wondered how many artists give up when their dreams are challenged, and he began to write inspirational lyrics to keep himself motivated. These lyrics would become “Lullaby,” the first song of his album T.I.M.E., which took him in a new direction as an artist. “I knew that I had a voice,” he says, “so I decided that I would learn how to sing and play the cello at the same time.” There was one problem: No one else was performing both voice and cello, and because there was no precedent, Ramseur was on his own.

Ramseur was already an established cellist, having performed for Maya Angelou on her 80th birthday, accompanied a principal dancer with the American Ballet Theatre, and played with the Grammy Awards Orchestra. Upon moving to Boston, he had experimented with performing at weddings and in T stations. Now, he was ready to push that experimentation further.

Singing and playing cello simultaneously was a new challenge, which at first he found daunting. If the pitch was sharp, he wasn’t sure whether to tune his voice to the cello, or tune the cello to his voice. “They have two different personalities,” he says, “so how do I bring out one instrument without stepping on the other instrument’s toes?”

He had a breakthrough when he realized he could learn by writing his own music, allowing one instrument to carry the melody, while the other accompanied, slowly rebuilding his confidence on both instruments. As he practiced, he became a better performer, “stretching myself like I wasn’t able to before, and expressing myself in deeper ways.”

Ramseur taught himself how to sing and play cello at the same time, and “Lullaby” is the first song on his album T.I.M.E. Video by Strewnshank Productions

After three months of practice, Ramseur was finally ready to perform for an audience—at the release party for T.I.M.E. It “wasn’t perfect,” he says, but it was unique. Venues and festivals are attracted to Ramseur’s distinctive combination of cello and voice, and in 2013, he performed at more than 50 Boston events, including The World on Stage at ArtsEmerson, the Kendall Square Concert Series, and the Boston GreenFest. The Boston Globe recommended his performance at the 2014 First Night Boston, and the Boston Music Awards named him the Gospel/Inspirational Artist of the Year.

In retrospect, Ramseur says the phone call from his concerned friend “opened my eyes to the reason so many people let go of their dreams. If I hadn’t believed in myself, or what I’ve been called to do, then Kendall Ramseur the recording artist would never have existed. I think about all the other artists who might let go of something that could touch millions of lives,” and he hopes that he can inspire others not only to persevere, but to attempt more than they thought possible. So what’s next for the singer, songwriter, cellist, and recording artist? This year, he’s performing on the hit TV show America’s Got Talent.

If You Build It, They Will Come

It was dusk as Greg Hum (CAS’10) pedaled down Commonwealth Avenue, battering the bucket drum between his handlebars. A Boston University desktop services specialist by day, Hum is a musician on his bike. He parked next to a Play Me, I’m Yours street piano in the courtyard of BU’s George Sherman Union as other bicyclists flocked from all directions, bearing instruments of their own. They ranged around the piano for the opening strains of Aretha Franklin’s rendition of “Respect,” and then, prompted by a cowbell, began to sing: “What you got? Baby, I got it! What you need? You know I got it!” It didn’t matter that the words weren’t quite right, or that they were off-key—the musicians added their guitars, shakers, clarinets, mandolins, trumpets, and tambourines, creating a wild cacophony that faded for a trumpet solo, then swelled into joyous noise again.

Greg Hum (CAS’10) and his friends gathered at the Play Me, I'm Yours street piano at the GSU for an impromptu performance. Video by Greg Hum

“The street pianos were the highlight of my year,” Hum says of the Play Me, I’m Yours Street Piano Festival, an international art project by British artist Luke Jerram that has traveled to 46 cities around the world. The festival “brings such joy to whoever gets to experience it,” says Margo Saulnier (’96), the project manager responsible for organizing Play Me, I’m Yours in Boston. Hosted by the Celebrity Series of Boston, the festival engaged the entire city, from the institutions that installed 75 pianos throughout greater Boston, to the local artists who painted them. BU hosted three pianos—at the East Courtyard, the GSU, and Kenmore Square—which were painted by CFA alums Ashley Teamer (’13), Kathleen Kennedy (’13), and Elizabeth King (’11).

BU hosted three pianos painted by CFA alums during the Play Me, I'm Yours festival. Photo by Cydney Scott

The festival “created a great sense of community and showcased the talent of the citizens who live here,” Saulnier says. Participants shared their talent and extended the community through social media, uploading videos, photos, and comments to webpages devoted to each piano. Inspired by the BU pianos, journalism student Kaylee Hill (SED’15, COM’15) filmed a short documentary, School of Theology students held a hymn flash mob, the Hip-Hop Club freestyle rapped, and the all-male a cappella group The Dear Abbeys broke their no-instruments rule to pose for a photo.

“I work at the Starbucks in the GSU and didn’t quite understand where all the lovely, sporadic music was coming from for a bit, but I LOVE IT!” Ella Clausen (COM’15) commented on the website. “The beautiful music spontaneously flowing through totally makes my shift.” At the Kenmore Square location, a local doorman posed on the piano seat, and high school musician Max DiRado performed his original composition, “Le Benjamin, So Long,” as strangers paused to listen.

“Each piano had its own community around it,” Saulnier says, and although the pianos weathered the elements in an urban environment, “the people who lived in the neighborhoods took care of them,” even covering them with sheets when it rained. As Play Me, I’m Yours proves, when we bring our instruments out of the recital halls and into the streets, communities will make music together.

[Correction to the print edition of Esprit: The original version of this article incorrectly stated that Courtney Miller earned an undergraduate degree from the Cleveland Institute of Music, when in fact she earned a master's degree from Cleveland and an undergraduate degree from Florida State University.]

From Sketch to Soundstage

As the production designer for films including Ghost, When Harry Met Sally, Patty Hearst, and Hitch, Jane Musky brings directors’ visions to life

By Julie Rattey | Photo courtesy of Paramount Pictures

Jane Musky’s heart sank as she stared into the closet. She’d thought the bedroom’s shag carpeting was bad, but this was far worse. The closet was maybe five feet long and three feet wide—and it would be the setting for half of her new movie. What the hell am I going to do? she thought.

The first few weeks Jane Musky ('76) spends brainstorming with a director is "the most exciting time" of her job. Photo by Getty Images

It was the late ’80s, and Musky (’76) was researching in San Francisco for Patty Hearst, a film about the abduction of the newspaper heiress and her two-month captivity in the closet of a Golden Gate Avenue apartment. The closet’s limitations were a cinematic problem. Production designer Musky and director Paul Schrader hashed out their options. Hearst had said she’d been blindfolded; how could they use that detail to their advantage? “We came up with this fantasy of what she thought the closet was,” Musky says. “The whole premise of the design, especially for the first half of the picture, was built around these wild fantasies of what she thought she was living in—what she thought she saw and what she thought she heard.”

Musky’s creativity and can-do attitude have served her well in her nearly 40-year career creating the defining look for stage, television, and film productions. Versatility has come in handy, too, as Musky’s résumé shows. She’s designed everything from the New York apartments in When Harry Met Sally and Hitch to the gritty frontier towns of Young Guns, and taken up eclectic projects ranging from the TV musical drama Smash to a biopic on rapper The Notorious B.I.G. (Notorious) to commercials for Garnier. Her theater background—including her teenage years painting high school musical sets and her studies at CFA—gave her a solid foundation from which to tackle any obstacle.

“I always tell young people who want to become designers, 'Train in the theater first.’”—Jane Musky

“I always tell young people who want to become designers, ‘Train in the theater first,’” she says. A stage designer’s experience can be a valuable asset in other fields, as Musky discovered when she and a friend ventured into television to design an after-school special in the ’80s. “We could make props, we could do whatever, so all of these producers thought we were the best thing that had happened to them in years.”

The experience was a turning point for Musky. Through her television contacts, she met future Oscar-winning directors Joel and Ethan Coen and designed their first feature (and her film debut), Blood Simple. She has since collaborated with other prominent directors including Mike Newell (Mona Lisa Smile) and Alan Pakula (The Devil’s Own).

Musky’s latest project—Squirrels to the Nuts, a comedy about a prostitute-turned-actress—reunited her with director Peter Bogdanovich, with whom she had collaborated on the 1988 comedy Illegally Yours. “I think the greatest challenge is trying to keep up with his sense of humor,” Musky says. In one instance, they worked to find a design element that would provide a backstory for an unlikely, volatile couple played by Cybill Shepherd and Richard Lewis. “Peter kept trying to think of something funny to show how much they really were in love with each other, so we invented this wedding portrait. We photoshopped them into this ‘60s, out-in-the-fields kind of thing. It became a centerpiece over their heads in one of the big scenes.”

“Everyone feels that with the electronic age, things have gotten so efficient and tailored that you don’t need a lot of the things that you used to need. That’s not true at all.”—Jane Musky

The first few weeks Musky spends brainstorming with a director is “the most exciting time” in her job. “You spend some time together trying to understand where the script’s going to be heading, but on top of that, the director’s style and how far they want to pursue different journeys.” Then Musky evaluates “how far I take an idea, whether it’s through color, through comedy, through drama, through period feeling.” Finally, she strives to “make it accessible enough that the audience can jump in and not feel intimidated by the design.”

All this design work needs to be completed within budget and on schedule—an increasingly challenging demand. “Everyone feels that with the electronic age, things have gotten so efficient and tailored that you don’t need a lot of the things that you used to need. That’s not true at all. I think if anything, what’s happening is there are too many shortcuts that are actually detrimental to films.”

Inadequate preparation time, smaller crews, and less funding can decrease production quality—something Musky says producers new to the industry don’t always understand. “They look at you cross-eyed, like, ‘What do you mean you need this?’” Musky’s level-headed approach to her work and collaborative attitude have kept her in the game and expert at adapting to the challenges of her field.

“The more successful designers I know are very grounded and pragmatic,” not divas who insist on their own way, she says. Her experience has also confirmed how crucial it is to “always be good to your crew and try to really foster those relationships for the lifetime of your career.”

The longevity of Musky’s career gives credence to the advice she’d offer aspiring designers: “Really make sure your craft is honed before you get out of school, because it carries you very far in this business.”

Multitasking Maestro

What do J. S. Bach, Leonard Bernstein, the Marsh Chapel Choir, and the Rolling Stones have in common?

By Lara Ehrlich | Photo by Megan Greenlee Photography

As the music and arts director for New York’s Trinity Wall Street church, Julian Wachner (’91, ’96) programs more than 600 events. Photo by Megan Greenlee Photography

Composer and Grammy Award-nominated conductor Julian Wachner (’91, ’96) answers his phone at the Jacksonville Airport baggage claim. This is his only opportunity for an interview, as he is about to embark on a trip with “five priests and a theologian.” This might sound like the opening of a bad joke, but it’s actually a retreat for the senior staff of New York’s Trinity Wall Street church, where Wachner is the music and arts director. Throughout the next four days, they will discuss the programming for the coming year, which will include more than 600 events. In his spare time, Wachner is also the music director of the Kennedy Center’s Washington Chorus and serves as a guest conductor at organizations throughout the country. As he gathers his bags and traverses the airport to meet his colleagues, he keeps up his half of the interview with the dexterity of a seasoned conductor.

You’ve said you chose to attend BU to earn a well-rounded education. How did academics impact your career?

My career is grounded in study. I didn’t jump from one huge musical success to the next; I had a long existence as a professor at BU and MIT, and then at McGill University. Now that I’m in my early 40s, I’m beginning to have the kind of success and recognition that some people have in their 20s. I’m very happy about the way it’s happened because I’m very calm and confident in my musical abilities. I feel like I have something to say on a human level, not just a musical level.

What do you want to say?

As a composer I tackle subjects like love and loss in Come, My Dark-Eyed One, which I wrote for Scott Allen Jarrett’s (’99, ’08) Back Bay Chorale, and thorny theological issues like in my first symphony, Incantations and Lamentations, and issues of the day like in Du Yun’s opera Angel’s Bone, which is about human trafficking. I’m trying to make a difference in people’s lives, whether to give them a glimmer of hope at Christmas, to make them think seriously about an intense subject, or to touch their souls.

“I don’t think I’m elitist in my choice of music or the way that I make music, and I think people feel that.”—Julian Wachner

The New York Times wrote of your Bach series at Trinity that, “no one would mistake the crowd at the free Bach at One concerts for one percenters. Many are tourists, stopped in their tracks by what they hear.” Who do you see as your audience?

I don’t think I’m elitist in my choice of music or the way that I make music, and I think people feel that. One of my models was Leonard Bernstein (Hon.’83), who felt that music should be for everybody, and that it is a way to bring people together. At our Trinity performances, we have people who don’t know where they are going to sleep that night and people who live on the Upper East Side all in one place together, creating a community.

The Trinity Wall Street Choir performed “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” with the Rolling Stones in December 2012. What inspired this collaboration?

I got a Facebook message from a critic whose husband is tied into the music business and was looking for a New York-based choir. She said, “It’s a famous rock group, and I can’t tell you any more than that.”

The show at Barclays Center in Brooklyn was the first US performance of the Rolling Stones’ 50th anniversary tour, and they wanted the choir to be a surprise for the audience. When I got out onstage for the sound check, Mick Jagger walked over and was like, “Hey, I’m Mick Jagger,” and I was like, “Yeah, I know who you are!”

It was the first time they had ever performed “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” with a live choir. You need a professional-level choir to sing that high C for as long as it demands; we were lucky we had three ladies who could do it. When the Stones decided to come back in June 2013, they asked me to recommend a choir, so I suggested BU’s Marsh Chapel Choir.

When the Rolling Stones asked Wachner to recommend a choir for “You Can’t Always Get What You Want," he suggested BU's Marsh Chapel Choir. Video by Chris Cummings

You were the University organist and choirmaster for Boston University’s Marsh Chapel for 11 years, and you recently invited the Choir and the Collegium Orchestra to perform at Trinity’s weekly Bach at One concert. Why did you invite the BU musicians to perform at Trinity?

I invited them to keep the relationship going between me and Scott Allen Jarrett, who was my associate at Marsh Chapel for about five years and is now the director. Between the two of us, we have maintained an incredible musical tradition since 1990, and it was logical to return to my alma mater to activate that professional scholarship.

How do you balance all of your professional roles and maintain your sanity?

The variety keeps my work fresh and alive, and the fact that I’ve prioritized my wife’s happiness over everything else keeps me balanced. I’ve done this enough now that I’m able to do the work without getting exhausted. In fact, the work feeds my creativity and my energy. My staff at Trinity knows that I’m studying scores at 6 in the morning and 11 at night, and conducting. Even some of the twentysomethings ask, “How do you have all this energy?”

Ready-Mixed Murals

Turning concrete mixer trucks into swirling, spiraling works of art

By Andrew Thurston

I spy with my little eye something…really big. And iridescent. And concrete-spattered.

Since graduating from CFA, Andrea Bergart (’08) has painted murals in the US and in Africa. Photo by Shanita Sims

We’re playing I Spy the Mural Cement Truck. There are three to spot: hot neon leopard print, African kente cloth, and paper clip-patterned. United Transit Mix’s 30,000-pound turning, churning art galleries—sprayed and rolled with bright murals by artist Andrea Bergart (’08) in 2013—are a kaleidoscopic spiral against the cement grays and muted steel reds of New York’s construction sites.

The company does a “lot of high-rise work” in Manhattan and Brooklyn, says United boss Tony Mastronardi, and the polychromatic trucks are out on the street most days. Since Bergart painted the trucks, her friends in the Big Apple have been playing I Spy the Mural Cement Truck. (Join the fun: If you spot one, post a pic here.)

Mastronardi has been in the construction business for 40 years and he’s never seen anything like this. “The truck was due for a paint job. She asked to do it; so I said, ‘Pick a truck.’ I’m open to new ideas.”

But a Lisa Frank-inspired, rainbow-colored, leopard-print cement truck?

“I wanted to see what I could get away with,” says Bergart. “The machinery is such a masculine thing, the construction sites are such macho places, so I wanted to see if I could get some hot pink and leopard print in there. I was surprised they let that happen.”

“I thought it was nice,” says Mastronardi. Nice enough that he let Bergart paint a second truck. And a third. (His favorite: the paper clip-daubed truck for “the colors, the design.”)

Andrea Bergart had “gotten a little bit tired of stationary images on a wall, the typical mural”—so she turned to cement mixer trucks for inspiration. Photo by Simon Biswas

Built to Scale

It started with a scale model. Bergart used a toy concrete truck to test different patterns and techniques, making short videos to see how the prints worked as moving pieces. The idea of painting the trucks had come to her out of the blue—a graffiti-streaked wall plus parked mixer trucks equaled inspiration—but she had also “just gotten a little bit tired of stationary images on a wall, the typical mural.”

Since graduating from CFA, Bergart has painted murals in the US and in Africa; she also teaches an after-school mural program for kids. Based in a mixed-use studio in Queens—an old sewing factory with her apartment upstairs and studio downstairs—Bergart keeps about 10 canvas paintings in progress, too, but likes breaking free to “collaborate and be outside. I love seeing a large image—it’s as simple as that. I want to see a really big image outside that’s not associated with a commercial agenda . . . I think art can be more accessible that way.”

“I accept that it’s a cement truck, a piece of heavy-duty machinery that’s going to get dirty and beaten up and backed into things. That’s part of it, too: having it decay.”—Andrea Bergart

Bergart has exhibited her paintings and textiles in New York, Massachusetts, and Texas, but she doesn’t just want to see her art hanging on exclusive gallery walls.

“The best work I see in New York makes me want to run back into my studio and make something, and that’s a feeling of excitement for me. I want the murals to be celebratory, and be funny and fun and happy. I think a lot of people are excited about the cement truck murals in particular just because they’re so accessible and they are out in the public; it’s not like you have to go to a studio or gallery to see them.”

For the first two trucks, Bergart used vinyl car magnets to make templates, sticking them on the steel drums to guide the painting. The paper clips design was more freehand: spray paint for a ghost image; brushes and rollers for the finish. The paint had to be industrial-grade, tough enough to withstand a pounding on the construction site and a daily wash down with additive-laced water.

“On each truck, I was trying to figure out the paint that would last the longest; at the same time, I accept that it’s a cement truck, a piece of heavy-duty machinery that’s going to get dirty and beaten up and backed into things. That’s part of it, too: having it decay.”

Becoming Unique

The final images don’t exactly match the sketches on the toy trucks. Bergart says her approach to all her work is to produce a lot, then edit a lot.

“Images change and I like that things can be included at the site,” she says. “I think it’s important to respond to the environment. I usually do a thumbnail sketch or a smaller drawing, but a painting is its own thing, too, and I want it to deviate a certain amount and be its own image.”

“I wanted to see what I could get away with,” says Bergart. “The machinery is such a masculine thing, the construction sites are such macho places, so I wanted to see if I could get some hot pink and leopard print in there.” Photo by Simon Biswas

The third truck—interjecting blue, orange, and green islands of color—only got its standout addition in the final moment: “I added paper clips during the last day; I thought it was recognizable and humorous.”

She hopes to do more work with United Transit Mix, but her next grand scheme involves a different kind of moving canvas: sailboat canvas. Bergart has a grant to travel to South Africa and plans to “celebrate the harbor in Cape Town” by painting a sail. There are no toy boats in progress yet. “I’m reaching out to sail manufacturers and trying to figure out how to translate an image and the best technique to execute that.”

So, while I Spy the Mural Cement Truck is open only to the 60 million or so residents and visitors to New York for now, expect the global edition to start soon.

Video by Simon Biswas