When Tennessee Williams first met Frank Merlo, a handsome, athletic, working-class Italian American from New Jersey, at a Provincetown bar in 1947, he was already the celebrated playwright of The Glass Menagerie. What began as a one-night tryst turned into a 14-year romantic partnership. During their years together, Williams wrote the Broadway hits A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Suddenly Last Summer, and The Night of the Iguana, while Merlo remained largely relegated to the background, his own ambitions put on hold to support Williams’ career.

Their often volatile relationship is the subject of Leading Men (Viking, 2019), an absorbing new novel by Christopher Castellani (GRS’00). The novel has two overlapping plots, one, focused on Williams and Merlo, cuts between the summer of 1953, when the two are vacationing in Portofino, Italy, and a decade later, when Merlo lies dying of lung cancer in a New York hospital, desperately awaiting a visit from the now-estranged Williams. The other involves a young Swedish woman, Anja Blomgren, Williams and Merlo befriend on their Italy trip, who soon goes on to become a famous film actress.

Castellani, the author of three previous novels, was a graduate student at Tufts when he picked up a copy of Dotson Rader’s memoir Tennessee: Cry of the Heart and learned of the relationship between Williams and Merlo. As a student in BU’s Creative Writing Program, he wrote a short story about the two men—“the only short story that I wrote in that entire program that felt salvageable,” he says. After earning an MFA, Castellani went on to write three novels about an Italian American family, inspired by his own family. But he kept returning to Williams and Merlo. “While I was working on the other books, I would kind of cheat on them by working on the Williams and Merlo story,” he says.

Leading Men took nearly 20 years to finish, but the wait has been worth it for Castellani, artistic director at the Boston-based nonprofit creative writing center GrubStreet. The novel has received rave reviews. In his New York Times review, Dwight Garner calls it “an alert, serious, sweeping novel [that]…casts a spell right from the start.” And from Publishers Weekly: the book “hits the trifecta of being moving, beautifully written, and a bona fide page-turner.”

Bostonia spoke with Castellani about Leading Men before his reading and Q&A with National Book Award–winner Julia Glass at Newtonville Books in Newton Centre on March 21, 2019.

Bostonia: When you first picked up Dotson Rader’s memoir of Tennessee Williams, what struck you?

Christopher Castellani began writing Leading Men while enrolled in BU’s Creative Writing Program. It began as a short story before becoming a novella and finally a novel. Photo by Michael Joseph

Castellani: “I was sort of paging through it and landed on this scene of Frank Merlo in the hospital waiting for Williams to visit him. Rader was writing about how he was disturbed by the fact that Williams wouldn’t come to see the man he’d spent 14, 15 years of his life with. And I was really moved by the tragedy of this man dying essentially alone, estranged from the man with whom he had had this long-term relationship.

But more than that, Frank was a working-class Italian American guy from New Jersey who ended up with the greatest playwright of the 20th century. I was, at the time, a working-class Italian American guy from Delaware, 200 miles south of where Merlo grew up, and I identified with Frank being in Williams’ world, in which he maybe never felt he belonged. I was in this ivory tower world of academia and felt like I didn’t quite belong, so I immediately felt this kinship with him and wanted to learn more about their relationship and how they navigated it. What was it like to be the partner of a great genius?

The book’s title is Leading Men, but there’s no question that this is Merlo’s story, not Williams’.

I didn’t feel I had anything new to add to Tennessee Williams’ legacy as an artist. It’s been well-researched and illuminated by better writers. This wasn’t meant to be a biography of Williams. It was meant to bring Frank into the light and give him his due and ask people to think about the man or woman behind a great artist. He definitely made himself subordinate to Williams. I wanted to write about that person, who doesn’t usually get the credit that is due.

This love story held you in thrall. You kept returning to it over nearly two decades, is that right?

I kept going back to them; I kept doing the research and rereading Williams’ plays and biographies. In the meantime, I was in my own long-term relationship, which was getting longer and longer as the years went on. I couldn’t have written about a long-term relationship like Williams and Merlo had back in 1999 when I was at BU, because I’d only been in a relationship for two years. When I finally really sat down to work on the novel, I’d been in a relationship for 14 or 15 years. And that had really taught me something about what it’s like for two men to be together. So I feel I brought a lot of that to the story as well.

The novel is populated with real-life characters: Truman Capote, actress Anna Magnani, and American writer John Hope Burns and his partner, Sandro. Why did you create the fictitious character Anya Blomgren, who becomes actress Anya Bloom?

There’s a version of this novel in which Sandro and Frank are telling the story in sort of alternating chapters. And when I was working on it, it felt too much like a compare and contrast essay, not a novel. And I realized it also felt very claustrophobic and very male. Women were so central to Williams and Merlo. I was feeling the need for a strong female character to interact with them. I had been reading the letters of Truman Capote from that same summer, and he had mentioned in a throwaway line that there was this Swedish mother and daughter in Portofino that summer and that they were sleeping with the same Italian fisherman. And immediately, I thought, one of those is my girl, one of those is the character. I don’t know what she’ll be doing in the story, but she is going to be in the story somehow.

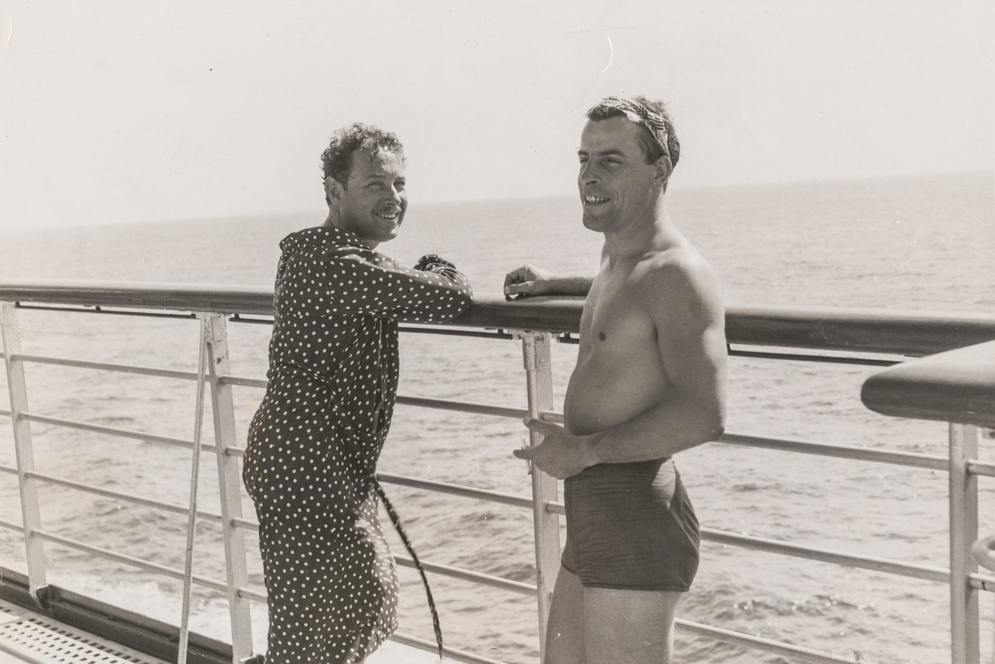

While Williams (front, left) was already a celebrated playwright when Leading Men begins, Castellani tells the story of his years with Merlo (front, center) from Merlo’s point of view. Photo courtesy of Tennessee Williams Collection, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University

I had originally thought Anya might be one of Williams’ actresses, like Vivien Leigh, but then I realized she would work better as a kind of foil for Frank. She would achieve the things that he couldn’t achieve. And she would belong to him. I wanted to write about that dynamic of the gay man and female friend, which I did with Frank and Anya. Looking at Frank through her eyes helped me see him more clearly than if I’d only been looking at him through Williams’ eyes.

What were the biggest challenges you faced in writing about Williams and Merlo?

I wanted to write about real people, a book in which everything could have happened, even though there’s no evidence that it did. So I was very careful not to put them anywhere where they definitely weren’t. I checked and triple-checked dates and cross-checked them with letters and other things to make sure that I was writing in the cracks of history and that everything in the book could have happened. To me, that was the fun part, but it was also the hardest part. I was nervous I was missing something.

In your novel, Williams gives Anya his last play, one no one else knows about. You actually wrote that fictional play and included it in Leading Men. I read that you put off writing the play as long as possible. Why?

That play is actually a version of the short story I wrote when I was at BU. I had the plot already, so it wasn’t like I was putting it off because I didn’t know what I was going to write about. My anxiety was: who am I to write in the voice of Tennessee Williams?

I don’t think I would have done it if I was attempting to write a good Tennessee Williams play. The fact that it fit into the plot that it wasn’t a successful play made me feel less intimidated…. I do think it works as a bad play he would have written.

The New York Times review says Leading Men is “an alert, serious, sweeping novel.”

You are the GrubStreet artistic director and also teach writing workshops and work with emerging writers. What advice do you give young people who want to write fiction?

My advice is to seek out a community of other people who also want to write…the writing always has to be done alone, but learning about writing doesn’t have to be done completely alone. Having a community has been essential for my development as a writer.

Revision has had a central part in your writing. Can you talk about that?

Revision is everything. In my first novel (A Kiss from Maddalena) and my third (All This Talk of Love), I gutted the middle out of both of those books: I took out hundreds of pages and then reimagined them and stitched it all back together. And in this book, revision came from all the different iterations (short story to novella to novel). I always tell students that the way into a story isn’t always the way out…. You have to be kind of ruthless about the pages you write and you can’t be committed to them, but they always teach you something: it’s just whether you’re willing to listen to them. Often they teach you that you have to spend months and months and months on them in order to learn that thing, and then once you’ve learned it, you need to get rid of it. It’s like scaffolding for a building: you don’t leave the scaffolding on after you’ve finished working on the building.

Related Stories

Straying: The Story of a Marriage, an Affair, the Aftermath

Molly McCloskey (GRS’20) talks about her 2018 novel

Robin Williams Revealed, with Big Help from BU Archives

New York Times author’s new book uncovers surprising truth about late comedian’s famous spontaneous riffs

Poet Crystal Ann Williams First Associate Provost for Diversity and Inclusion

Former Bates College administrator’s goal: to build on BU’s forward momentum

Post Your Comment