Long before crowdsourcing, there was the Bill of Rights. In 1788, the US Constitution was ratified only on the strength of promises to redress its inadequate rights guarantees. With most of the country likely opposed to the document, backers ultimately added 10 remedial amendments that became the Bill of Rights.

If heeding the wisdom of crowds worked for our ancestors, why not for us? Greg Blonder asks. The College of Engineering professor has founded We Amend, a nonprofit to crowdsource a second Bill of Rights: ranking potential amendments to pinpoint the most popular and then mass-drafting their wording, for ratification “by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states, or by conventions in three fourths thereof,” as prescribed by the Constitution’s Article V.

We Amend would arrange both online discussions and public meetings for those Americans who lack internet access.

Blonder, a professor of the practice of mechanical engineering, is known at BU for applying his expertise as a scientist and former venture capitalist to nonscientific passions, including good barbecue, good wine, and now, good government. The latter needs fixing, he argues, as politicians refuse to legislate clearly expressed public preferences on a host of issues, from higher taxes on the uber-rich and paid maternity leave for workers to lower drug prices and net neutrality.

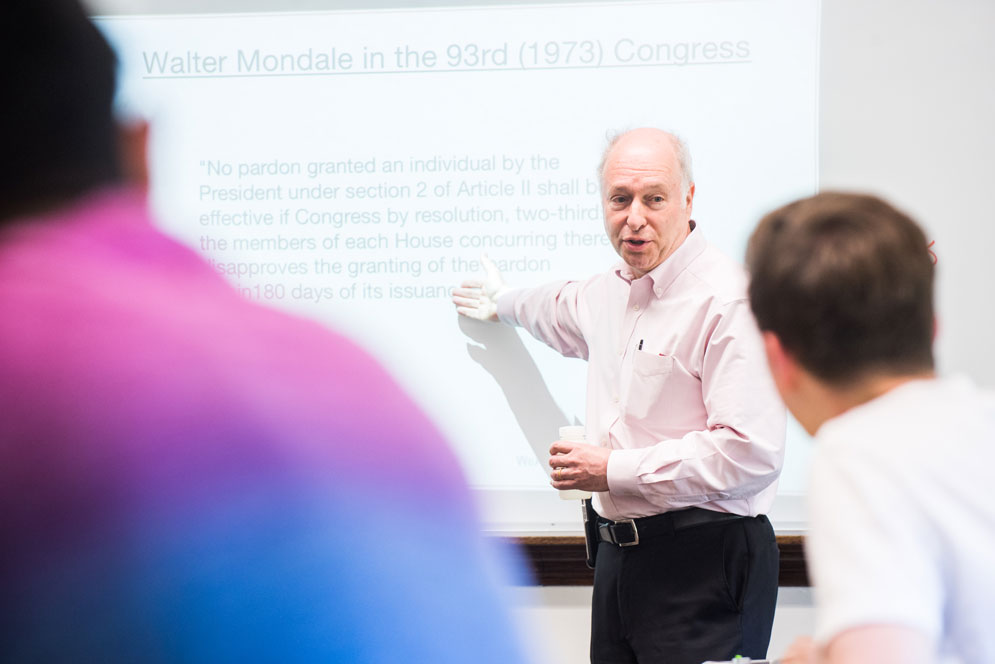

To test-drive the feasibility of crowdsourcing a new batch of amendments, Blonder stopped by Brookline High School late May 2019 for a discussion with a minicrowd, the 16 students in Jenny Longmire’s Advanced Placement US Government and Politics class. Their assignment: hash out an amendment reining in presidential powers to pardon, a topic President Trump made topical by mulling presidential forgiveness for accused American war criminals in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts.

Going around the room, the academically high-octane group read drafts they’d prepared of varying amendments, seeking commonalities. Their debates were engaged and passionate, but “there seems to be general agreement that a president shouldn’t pardon himself,” Blonder noted. “Others didn’t want him to be able to pardon his friends, relatives, cousins, aunts—and probably sisters-in-law and stepfathers.”

What about a pardon issued before the justice system has a chance to deal with a possible wrongdoer? Blonder asked. “If I go and break into the Watergate, the president can pardon me immediately for any crimes,” before any trial or conviction, he pointed out.

Senior Caleb Lipsitt suggested the Supreme Court could review the pardon for unconstitutionality. Given that SCOTUS members can change, Blonder pressed, would Lipsitt be OK with its review, if, say, “Ruth Bader Ginsburg steps down and we put on a rabid conservative?”

“I think you’re asking the wrong person,” the class conservative replied, to knowing laughter from his classmates.

“The answer is yes,” a smiling Blonder shrugged, throwing in the towel.

Brokering a national, online conversation

The Brookline High exercise suggests that the actual crowdsource discussion would need experts and real-life test cases available for consultation, says Blonder, who’s working to line up similar sessions at colleges and town meetings around the country in coming months. He’s also interviewing vendors of crowdsourcing software that We Amend will need to harvest the most popular of a potentially huge number of proposed amendments, and then discern the most broadly acceptable wording of those amendments, before submitting them to Congress for subsequent submission to the states.

Blonder is recruiting a board for his organization, which he ran by cognoscenti—law and political science professors as well as politicians—“and they’re all over the place,” he says. “There are people who say you’ll never see an amendment passed again in America because we’re so polarized. Just give up.” Others say that “this is really a very creative way of thinking about it.”

Still others have lauded the idea, he says, but think it would be insurmountably hard to pull off. Blonder doesn’t disagree that it will be time-consuming. From now until states vote on crowdsourced amendments would be five or more years, he predicts, and require at least $50 million that the organization would have to raise to organize, educate, and lobby for its Bill of Rights.

“Since the founding of the country, something like 11,000 amendments have been introduced in Congress, and 27 have been approved,” he says. “Of course, most of those [11,000] were just stunts—people pandering to their base: they knew there was no chance. We’re only interested in going with amendments that have a chance of being approved.”

For example, states are now passing proabortion and antiabortion laws in expectation that the Supreme Court may strike down Roe v. Wade. “Whether we can come up with an amendment which would be acceptable to three-quarters of [the states]—what would the language be?” he says. “There are deep moral issues; this is a very difficult subject.… But we do know that two-thirds of America think some limited abortion rights, whether it’s first trimester or whatever it is—there’s broad support for that.

“That’s what the crowdsourcing would do,” Blonder says. “If they can find one that has broad support, where you could imagine…three quarters of the states are for it, that would make it through the funnel.” That means some amendments might not meet his or other board members’ personal approval: “I’m not going to sit here and write my favorite 10 amendments.”

An engineer with a citizen’s passion for politics

Having been a venture capitalist and a CEO before academia, “I have a certain preconception about how a well-run organization works, which is not the way government works,” Blonder says. As a VC, “I was the seventh-inning relief pitcher. I would come into a company that was failing, figure out what was wrong…and either sell it or fix it and make it successful. You don’t leave things ambiguous if they can be made sure,” in business and in science. “And the law is not like that,” with its conflicting and evolving understandings of the Constitution and court decisions regarding it.

A crowdsourced Bill of Rights would echo the public-driven process that molded not only the original Bill of Rights, but popular referenda in various states as well. Blonder points to Florida, where voters in November 2018 enacted voting rights for felons. Other states’ voters have created independent redistricting commissions to draw congressional district boundaries that aren’t gerrymandered.

State-level lawmaking by referendum has been criticized for creating ill-informed and expensive mandates, and for being vulnerable to misinformation from deep-pocketed interest groups. But supposed legal experts in Congress and the courts shouldn’t puff themselves up, Blonder says. Similar bungles have bedeviled their lawmaking over the centuries, from Constitutional amendments like Prohibition to Supreme Court decisions like Dred Scott, which upheld slavery.

If We Amend “could just get people thinking about their government, realizing that they’re part of the solution,” the effort will be worthwhile, he figures. Given our polarized, gridlocked politics, he adds, it may be the only way to translate public wishes into public laws.

Related Stories

University Rescinds Bill Cosby’s Honorary Degree

Determination based on actor’s sworn testimony

“Find That Next Bill Cosby”

Famed actor to SED grads: go proudly into a tough profession

BU to Join Second AAU Campus Sexual Misconduct Student Survey

With 33 institutions participating, it’s expected to be among largest sampling ever

Post Your Comment