Last winter’s record-setting snowstorms made life tough for most Bostonians, but few had it tougher than Brian Fitzgerald, chief weather observer at the Blue Hill Observatory and Science Center.

The observatory, atop Great Blue Hill in Milton, Mass., has kept America’s longest continuous daily weather record, dating back to 1885, and it was Fitzgerald’s job to make sure the record stayed continuous. That meant a daily drive up the narrow, winding access road, through the woods, to the summit, at 635 feet above sea level the highest point on the East Coast south of Maine within 10 miles of the Atlantic Ocean. And it meant recording temperature, barometric pressure, wind, cloud cover, and other data at 7 and 10 a.m. and at 1 p.m.

Having worked as a weather observer on Mount Washington for two years before taking the Blue Hills job in December 2013, Fitzgerald (SED’15) was the staff member best suited to the challenge. Because of emergency communications equipment at the summit, the state, which owns the property, kept the road open, he says, and his Volkswagen Golf took most storms in stride. That is, until the morning after the fourth and final blizzard, when he reached the last and steepest stretch of the road, already reduced to a narrow corridor between snowbanks.

“I looked up and there was a wall of white” where the road should have been, Fitzgerald says. Powerful westerly winds had blown tons of snow over from the upper reaches of the Blue Hills Ski Area next door. “In a not-very-good, instinctive way, I just floored it, thinking maybe I could break through. But the road the rest of the way up was filled four feet high with powder.

“It was actually the least dramatic crash ever,” he says with a smile. “The snow slowly engulfed the car, and I came to the slowest stop of all time. It was like being caught in a big pillow.”

The Blue Hill Observatory and Science Center in Milton was built in 1885. The original tower was replaced with the current structure in 1908.

Fitzgerald hiked the remaining few hundred yards to the observatory, then called those responsible for plowing and said they’d better bring a front-end loader.

The hilltop often gets some serious weather. In New England’s notorious Hurricane of 1938, the observatory recorded a wind gust of 186 miles per hour, the highest ever directly recorded in a hurricane in the United States. After another of last year’s blizzards, Fitzgerald spent more than 48 hours straight at the summit.

“He probably couldn’t have gotten down anyway,” says Charles Orloff (SED’64), executive director of the nonprofit observatory.

Although Fitzgerald is not a meteorologist, he has long been fascinated by weather. The Connecticut native was turned off in high school by the math required and graduated from the University of New Hampshire with a BS in natural resources and environmental education. The Mount Washington job began with an internship there, and he also worked jobs combining outdoor activities and education for REI and the Appalachian Mountain Club. Groups of schoolchildren come to the Blue Hill Observatory often for tours, and he loves talking to them and explaining what happens at the observatory. While working there, he’s studying for a master’s in science education at the School of Education.

A 360 degree view—from Boston’s skyline to Mount Monadnock

On a sunny fall morning, warm for late October, those bitter blizzard days seem far away. Fitzgerald grabs a cord in the observatory’s weather center, pulls down a wooden staircase, and climbs through a hatch to the top deck of the tower. Clinging to the battlements are a sunshine recorder and 10 different anemometers to measure the wind. The 360-degree view includes the Boston skyline, 14 miles to the north, beyond the fading rust-and-yellow foliage of the Blue Hills Reservation, part of the Department of Conservation and Recreation MassParks system.

Charts on the wall of the crowded observatory office below show long-term trends. The average wind speed at the observatory has dropped significantly over time, partly because of increased vegetation as the area has returned from farmland to woodland, but also, perhaps, because of climate trends. Precipitation has been increasing steadily over the decades, correlating with an increase in the average annual temperature. Average snowfall hasn’t changed much, but extreme snow events are more frequent. September 2015 was the warmest September on record at the observatory. Climate change is often on Fitzgerald’s mind.

The weather station, previously known as the Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory, was founded 130 years ago by meteorologist Abbott Lawrence Rotch, an MIT grad and scion of a prominent Boston family. Rotch bought the land and built the original tower with his own money. His observations, first recorded on February 1, 1885, eventually earned him an international reputation, and in 1908, he tore down the original tower to build the current three-story structure. Under him and his successors, the observatory was instrumental in developing the use of kites, weather balloons, and radiosondes, the battery-powered instrument packages that go up in balloons and transmit data back, for gathering information.

The observatory was run by Harvard from 1912, when Rotch died and left it to the university, to 1971, and later the National Weather Service (NWS), until the latter bowed out and the underfunded nonprofit Blue Hill Weather Club took over. Recently a Kickstarter campaign raised $8,000 for a new anemometer.

From the top of the tower, Fitzgerald points out his girlfriend’s new workplace—the tiny golden dot that is the Statehouse dome. When he worked on Mount Washington, his schedule was eight days of 12-hour shifts followed by six days off, usually spent traveling to Brooklyn to see her. Now they live in Jamaica Plain.

The view goes far beyond the Statehouse, as much as 70 miles northwest to Mount Monadnock in southwestern New Hampshire. “Pretty good fire going there,” Fitzgerald says, turning south and pointing to a plume of white smoke rising from the woods near Brockton.

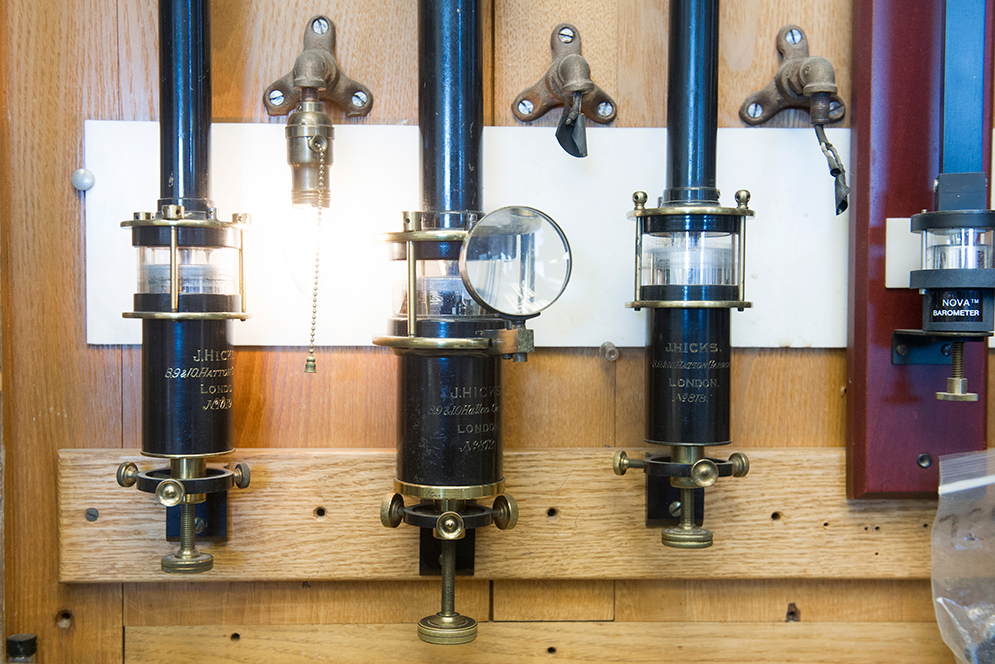

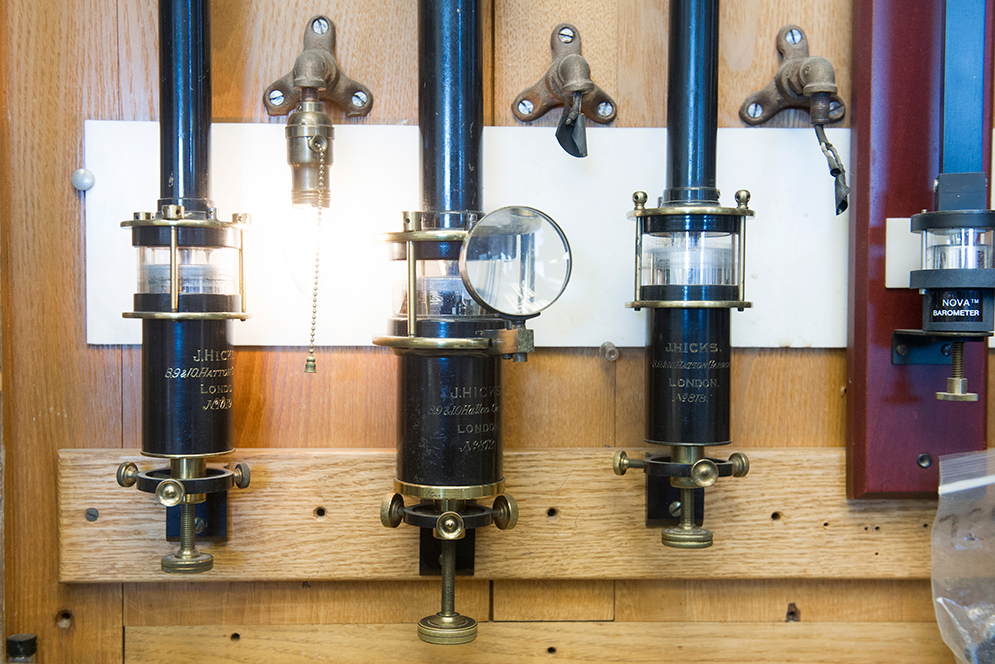

The oldest mercury barometer at the Blue Hill Observatory and Science Center (second from left) has been in use since January 1, 1888, and is still used to gauge the accuracy of the other barometers.

The magnifying-glass-like focus of the Campbell-Stokes sunshine recorder burns into paper to record sunshine minutes per day.

An array of anemometers atop the observatory tower.

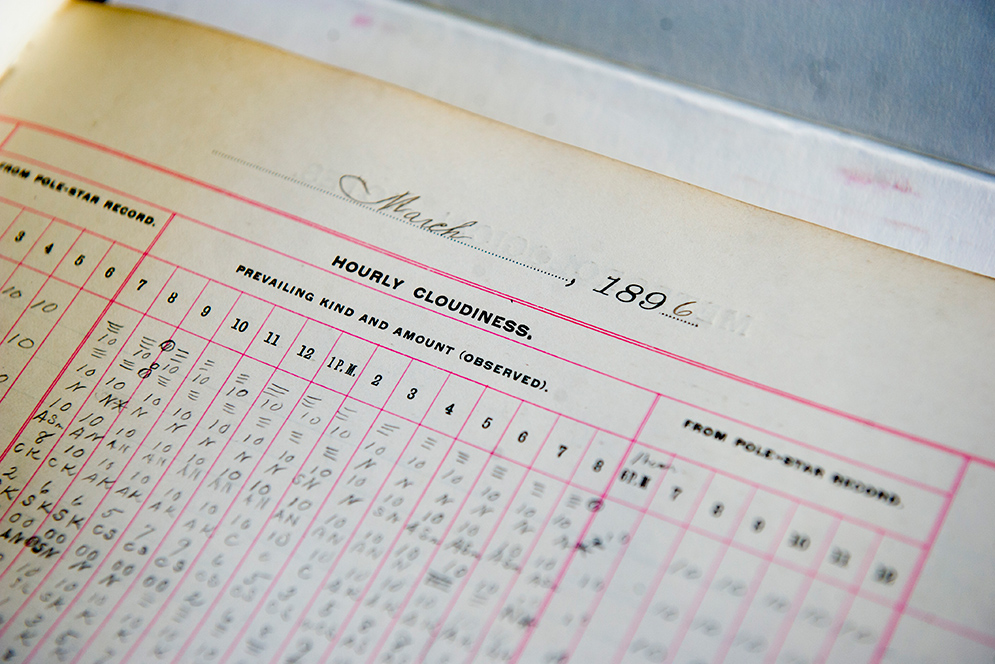

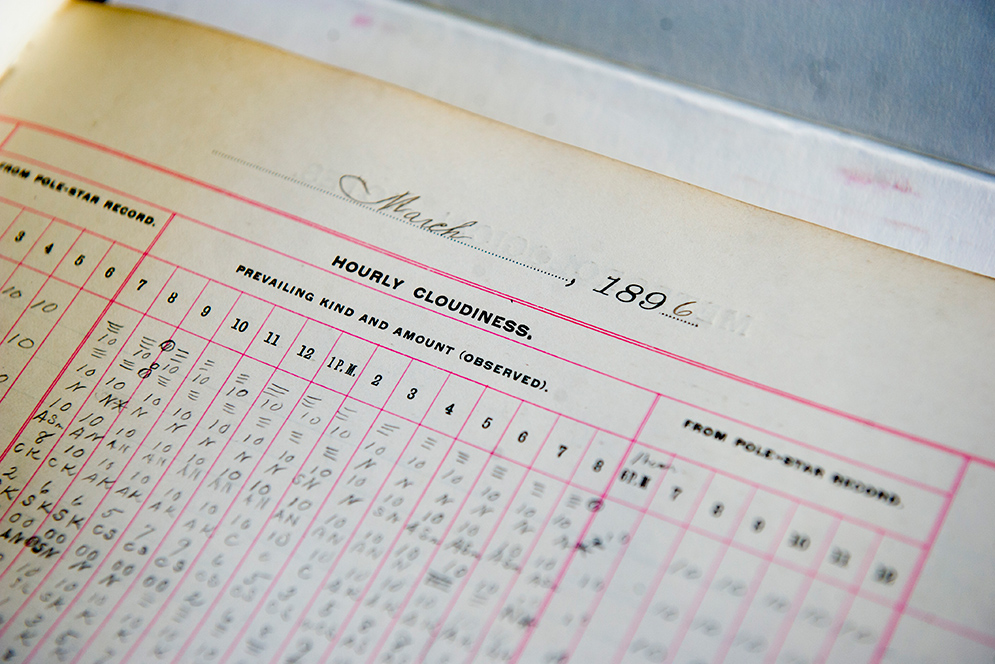

Handwritten notes from an 1896 weather log.

The ink is still wet as the official peak gust recorder registers wind speeds at the observatory atop Great Blue Hill.

The records from the previous day show the gusts measured by the three-cup anemometer at Blue Hill on October 26, 2015.

These strings of human hair are held under tension as part of a device to measure the relative humidity at the observatory.

In the yard outside the observatory, the Hazen Shelter houses official temperature and humidity recording instruments.

The hand-cranked ombroscope measures the start and stop times of rainfall throughout a day. The droplets of water leave their mark on inked paper wrapped around a cylinder.

When Fitzgerald looks at the sky he sees broken stratocumulus at about 6,000 feet and a thin cirrus layer at 25,000. In addition to the instruments on the battlements, there are others in the weather center and in a fenced enclosure outside. Redundancies and automated instruments are built into the system—and the NWS has its own computerized system here as well—but the station’s key instruments are antiques. Fitzgerald has learned to play them like a master violinist, tending to their delicate adjustments and idiosyncrasies, cutting off the paper charts each day, using an eyedropper to add ink to the graphing barometer.

The Campbell-Stokes sunshine recorder atop the tower is basically a small crystal ball that when the sun is out focuses its rays to burn a thin line onto a paper scroll. It’s just like frying an ant with a magnifying glass, Fitzgerald says. Although it’s a low-tech system, the device is actually a 1990s replacement for the 1893 original, stolen several years ago by athletic teens who climbed the tower. Because the observatory is on the National Register of Historic Places, the FBI investigated. Although the original was returned after the replacement was obtained, the incident left an unfortunate two-week gap in the sunlight records, Fitzgerald says.

The crown jewel of the observatory, though, is a thin glass-and-metal tube in a wooden case on the office wall—a mercury barometer purchased by Rotch from J. Hicks of London. It has been reading the atmospheric pressure at Blue Hill since January 1, 1888.

A record 150.8 inches of snow

In good weather or bad, Fitzgerald’s reporting obligations include one report a day to the observatory website and an email list, as well as posting a daily weather discussion on a topic of his choosing on the website. The climate record is sent monthly to National Centers for Environmental Information, and observations are used for research and often noted by local media. Last February, Fitzgerald was interviewed by WBUR, BU’s National Public Radio station, and the Boston Globe.

“The one thing we can’t do unmanned is measuring snow,” says Orloff, so Fitzgerald, or a part-time observer, has to be on hand during storms “to keep that record homogenous.”

“The correct way of measuring snow is every six hours, after you take a measurement, you clear off the white board it is on, because snow settles and packs down and/or melts. You want to get a true reading. So you have to be up there to do that,” Orloff says.

A record 150.8 inches was the total for winter 2014–15, which also had the greatest snow depth ever recorded on the ground. “The day after Valentine’s Day we recorded 46 inches of snow on the ground,” Fitzgerald says. “We didn’t have a stake that was long enough to measure it, so we were using two rulers.”

The value of having Fitzgerald on hand to manually record snow depths was shown when the last storm pushed the NWS automated precipitation gauge at the site, like some Bostonians, into a temporary mental breakdown—it reported the inconceivable water equivalent of 40 inches of snow during a single hour.

With winds blowing up to 80 mph, Fitzgerald at times trekked into the woods in snowshoes to get snow-depth readings from a measuring station in a more sheltered location. All of it added up to lots of long days and exposure to the elements, but Fitzgerald was rewarded with a snowfall record.

“With all that work, you want it to mean something,” he says. He has bought a small SUV.

Fitzgerald, who has almost finished work on a master’s degree in education from the School of Education, answers weather questions from visiting fourth-graders from Dorchester’s Neighborhood House Charter School.

Along with visitors who hike up through the woods from Mass Audubon’s Blue Hills Trailside Museum, many school buses climb the access road in good weather, sometimes bringing hundreds of children a week. “We were very fortunate to get Brian,” says Orloff. “We were looking for someone who not only knows climate research, but loves kids and wants to work with them.”

“I went to school for science and after the fact realized I really enjoyed teaching, but didn’t really have any of the theory or background for that,” Fitzgerald says. “So here I am circling back, learning the theory and practice at SED; I figured out how to take my unique experiences and informal education and link them up with the more traditional route of schooling.

“There are some basic principles in education, like creating a rich and healthy environment for learning, and it doesn’t really matter if you’re in a classroom or on the side of a mountain or in a weather observatory.”

He says that “the data we have here is a remarkable teaching tool, because it provides clarity in a way that doesn’t always exist in science. When we teach students and the general public about science, that data help us to show them the nature of climate in our backyard.

“I get a lot of joy from doing hands-on science and explaining that science to other people,” he says. “If in five years I’m still doing something similar, playing the role of scientist and the role of explainer, I’d be happy, whatever tower or mountaintop or classroom that may be.”

The Blue Hill Observatory and Science Center website has voluminous weather information along with hours and directions for visitors. Tours are given Saturdays, Sundays (except in January), federal holidays, and Patriots Day, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., year-round; Sundays in January and all weekdays by appointment only. Admission is $4 for adults, $2 for ages 5 to 17, free for children under 5. Call 617-696-0562 for details or information on group tours. Visitors may use the access road off Canton Avenue (Route 138) by calling ahead, but most use the hiking trails from parking lots at Mass Audubon’s Blue Hills Trailside Museum or the Blue Hills Ski Area on the same road.

In paragraph #7 of this piece, you say that in 1938 the Blue Hill Observatory experienced a gust of wind measuring 186 mph — “the highest ever recorded in the United States.” I believe that New Hampshire’s Mount Washington is in the United States, and until last year it held the world record for the highest gust of wind — 242 mph.

Thanks — Dan Levin

Dan, you’re right, I’ll fix that in the text. I somehow dropped the phrase that it was the highest in a hurricane. The Mt. Washington gust was the all-timer until recently. I just read the story of that 1934 day on Washington online, quite a tale: https://www.mountwashington.org/about-us/history/world-record-wind.aspx

What an interesting and informative article. Great Blue practically is in my back yard and yet I knew so very little about “what goes on up there”. I am impressed.

Thank you Brian Fitzgerald for all that you do, especially for sharing your observations with the younger visitors. Hopefully some will be inspired to pursue careers in science.

And thank you, Joel Brown for bringing this story to our attention.

Kathy A. Amico, SPC ’70.