Fragments of the Past: The Exchange Buffet, Building a Business on Trust for 78 Years

By Peter Szende and Jeanne Pak

It is late fall of 1885, and Arthur Maloney is the quintessential stockbroker at the New York Stock Exchange. He is busy taking care of his clients and is always rushing around with very little extra time—Maloney can barely spare a few minutes for a quick bite, much less a leisurely lunch; nor does he want to spend that precious time waiting for food to be served when time is of the essence.

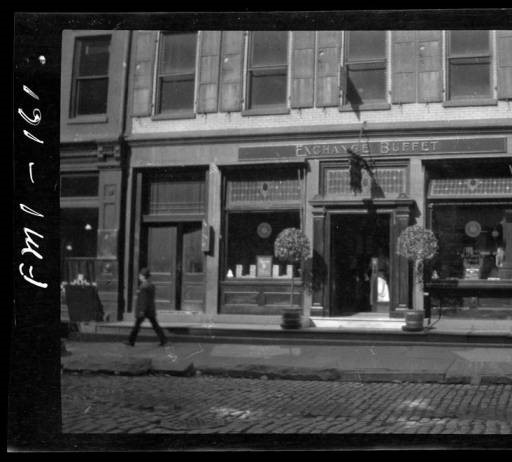

This quick vignette offers a small taste of what life on Wall Street was like and highlights an opportunity for the hospitality industry of that age to pivot in response to customer needs. Realizing the increasing demand for a quick bite by working stockbrokers resulted in the idea of the Exchange Buffet. On September 4, 1885, the Exchange Buffet opened right across from the New York Stock Exchange, effectively targeting stockbrokers and other male employees of the financial district.

Even more notably, the new spot on the block operated on an honor system.

Exchange Buffets: Good Food at Moderate Prices

Like Arthur Maloney, the majority of New Yorkers were always rushing around regardless of the circumstances (Smith, 2015). Because of this, lunch rooms of different sorts had begun to open starting in 1834 (Whitaker, 2004). For example, the well-known cafeterias, popular during the 1880s, pioneered the self-service concept (Smith, 2015). However, one of the standout restaurant styles that rapidly gained popularity was this exchange buffet, in part due to its unique style of service and payment. Based on data from the past, restaurant historians have labeled the Exchange Buffet as “the first waiterless restaurant in the United States” (Haley, 2011, p. 183).

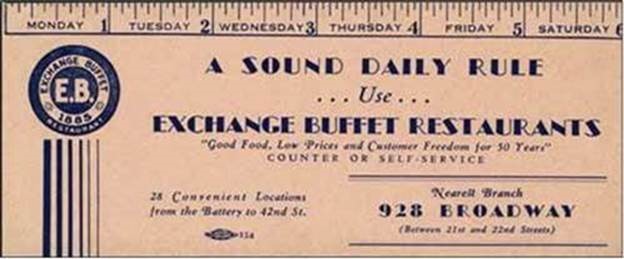

From an operational standpoint, Exchange Buffet offered a variety of different dishes to their customers. For example, they carried about twenty-five main entrée items, not including other items such as desserts and sandwiches (True, 1922). The Exchange Buffet, moreover, catered to a specific market: businessmen. The typical male guest would come into the restaurant and choose anything from sandwiches to cakes and eat it at a stand-up table. Then, he would choose his like of beverages (True, 1922, A Restaurant, 1922).

The Exchange Buffet’s popularity was due to its idea to provide faster service to its guests by removing the middleman. Instead of having to wait for a server, customers could easily choose their food and eat it right away at a counter (Smith, 2015). Of course, if a customer wanted to be served, there was table service provided as well (True, 1922).

Honesty Pays Off

Even given these new and unusual features, the most prominent characteristic of Exchange Buffet was that they viewed each customer to be honest, assuming that they looked at the prices of the food were displayed (True, 1922).

This restaurant, however, probably used inspiration from another luncheon joint in New York called Dennett’s. About two years before the Exchange Buffet was founded, Dennett’s already operated on an honor system. As the Exchange Buffet would later implement, customers of Dennett’s would eat their food and were charged according to what they reported to the cashier at the end of their meal (Grimes, 2009). Later, a Chicagoan named John Kruger popularized this concept and renamed this honor system-based restaurant style as a ‘conscience joint,’ where customers were able to maintain their own tabs (Mariani 2013).

“Pardon me…didn’t you make a mistake?”

When dining at the Exchange Buffet, customers would make their order, clear their dishes when done, and tally their own bills (Smith, 2015). The employees, on the other hand, operated in this manner: the “call boy,” or checker, would be the customer’s first contact for reporting their meal totals. The call boy would then shout the amount so that the cashier and spotter could hear it when handing the customers their final check (Smith, 2015; Stockard, 1922; True, 1922)—this shouting was reminiscent of the loud work environment of the stock market.

Although the honor system was based on trust, the spotter was there to keep an eye of customers—especially walk-ins. With this in mind, ironically, one former customer recalled in 1977: “Almost everyone had a “ham on rye and coffee” – 35 cents. Many had indeed enjoyed a full turkey dinner” (Fallath, R., 1977, p. 55). According to urban legend, some customers did get away with eating a certain meal—perhaps one of those full turkey dinners—but neglecting to pay the full amount for it; however, he would return the next time and make up the difference for what he could not pay before (Shanley, 1963). As one spotter put it, if guests forgot to pay for something as simple as a side, “they [would] register innocent surprise when I remind[ed] them of what they neglected to pay for” (Stockard, 1922, p. 41).

The concept of the honor system is what allowed the business to thrive. However, the owners did not believe it was necessary to advertise the way Exchange Buffet operated during the first three decades of their business. It is true that the system was special and incomparable to other food chains, but there was a concern in publicizing it as such would “attract an undesirable class” (True, 1922, p.109). According to an observer in the 1930s, the restaurant “hasn’t lost much money because of chisellers” (Ross, 1937, pp. 6-7)—notable in a city where every person seemed to be suspicious of each other. The system, therefore, proved to be effective.

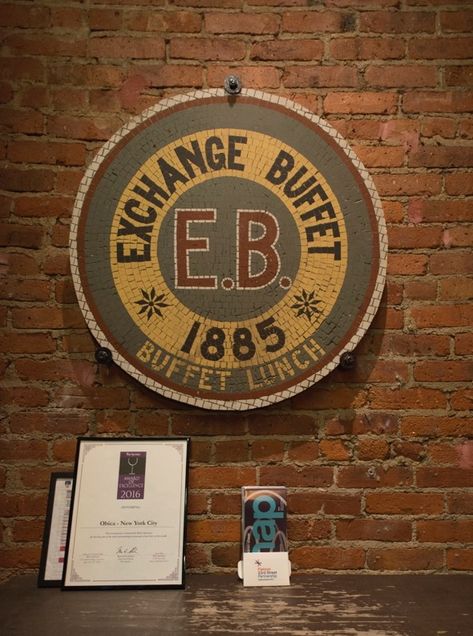

The old signage pictured above can be found at the entrance of Obicà Mozzarella Bar Pizza e Cucina in New York City, a restaurant opened a few years ago. This amazing piece, thought to be a part of the floor of the Exchange Buffet, was found by the current owner of the property, who decided to display it on the wall of the restaurant as a remembrance of the history of Exchange Buffet. The Exchange Buffet, also called the E&B, was famously nicknamed as the “Eat’em and Beat’em” restaurant (Grimes, 2009).

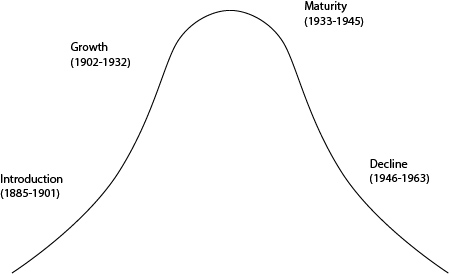

The Buffet Exchange Timeline

Like any other product, the Exchange Buffet progressed through various stages. To illustrate the four stages of its life cycle curve and trace its timeline, let’s examine a few pertinent various newspaper and magazine articles.

INTRODUCTION (1885- 1901)

- The restaurant product was brought to the market in 1885 (A Restaurant, 1922).

- The Exchange Buffet began to branch out in 1901 (A Restaurant, 1922).

GROWTH (1902 -1932)

- The Exchange Buffet started to pay dividends (The Trend, 1922).

- The product expanded to thirty locations in NYC (The New York Times, September 28, 1921).

- Employees were eligible to become stockholders (The New York Times, October 6, 1921).

- The company generated a revenue of over 6 million dollars per year. The 35 stores of the chain extended from Manhattan to Brooklyn and Newark as well (A Restaurant, 1922).

- The Exchange Buffet stock increased from 62,500 to 250,000 shares (The New York Times, April 1, 1922).

- The Exchange Buffet paid a dividend to its shareholders (The New York Times, April 14, 1922).

- A maximum of 5,000 shares per person became available for purchase (The New York Times, June 30, 1922).

- The Exchange Buffet shares were listed on New York Stock Exchange (The New York Times, October 14, 1922).

- Windsor Restaurant, a subsidiary of the Exchange Buffet, opened to female customers (The New York Times, June 15, 1927).

- The Exchange Buffet reported a rise of their net profit (The New York Times, February 28, 1928).

MATURITY (1933 – 1945)

- Exchange Buffet reported a net loss (The New York Times, February 24, 1934).

- The ompany reduced its capital to minimize the appearance of net loss (The New York Times, August 7, 1936).

- Management level employees received a bonus (The New York Times, August 7, 1936).

- The Exchange Buffet operated 22 stores; for the first time in 10 years, they paid a dividend (The Washington Post, July 1, 1943).

- For the first time since 1934, the company reported a profit instead of a loss (The New York Times, August 5, 1943).

DECLINE (1946 – 1963)

- The president of the Exchange Buffet, Gardner W. Millet, left the company, and his family sold their stock (The New York Times, June 7, 1946).

- The Exchange Buffet shifted into the hotel business (The New York Times, March 8, 1947).

- The Exchange Buffet took the Longchamps Restaurant chain (The New York Times, July 16, 1947).

- After a couple years, the Exchange Buffet noticed a decline in their profits (The New York Times, November 22, 1948).

- In addition to their 20 stores in New York, the Exchange Buffet took over operating Thompson’s Spa restaurants in Boston (The Boston Globe, March 14, 1949). [Please refer to Boston Hospitality Review, Fall 2012]

- Over 400 employees of the Exchange Buffet went on strike, causing the remaining branches to shut down. The union demanded higher wages and benefits for all employees (The New York Times, April 2, 1954).

- The NYSE made preliminary considerations to delist the Exchange Buffet (The New York Times, April 24, 1956).

- NYSE officially removed the Exchange Buffet (The New York Times, May 17, 1957).

- After 78 years, the Exchange Buffet filed bankruptcy. The last Exchange Buffet closed its doors on October 25, 1963 (The New York Times, November 9, 1963).

The once dominant food service operation ended up declaring bankruptcy. By simply glancing through the above timeline, it is clear that after the second World War, the company had been struggling to adapt to the changing market. To overcome threats, after the resignation of the President, the new leadership tried different—and desperate—turnaround strategies.

Does Honesty Really Pay Off?

Dennett’s did not start making a real profit until they dropped the honor system concept. Business came easier when they adapted to the ticket system (Grimes, 2009): “The trust method evidently gave way to a ticket system whereby the counter help would punch the amount of each dish selected by the customer” (Whitaker, 2004, p. 72). Similarly, merely three years after the introduction of John Kruger’s “Conscience Joint” venture, some cafeteria operations in Chicago were forced to drop the honor system due to the serious loss in profits (Jacob & Benzkofer, 2014).

Closing Words

Despite these examples from the past, variations of honor systems are still widely used in the restaurant industry. For example, to differentiate themselves from competitors, Macaroni Grill, a casual dining chain, has become famous for their honor system: guests themselves report the number of glasses of the house wine they have consumed. Each of the numerous examples of pay-what-you-want restaurants has its own story, typically based on a social experiment or an innovative marketing gimmick to increase appeal of the product.

The real roots of Exchange Buffet’s honor system are in Central Europe. Even nowadays, in many old fashion family style restaurants, instead of automatically receiving a check upon payment, customers need to call the head waiter over to the table “Herr Ober, zahlen bitte” and guests have to recite to the headwaiter tableside what they consumed and then a manual check is presented to them. This interaction between the guest and service provider creates a relaxed, congenial feel that is based on trust as guests can sometimes get away with “forgetting” a side order or second glass of beverage. The headwaiter’s eagle eyes are carefully scanning the table, and they have a pretty good idea of what has been ordered, in this act the restaurant becomes complicit of the guest in this minor infraction that creates a shining moment that is called hospitality.

Dr. Peter Szende has over 25 years of management experience in the hospitality industry in both Europe and North America. He joined the Boston University School of Hospitality Administration as an Assistant Professor in 2003. He was promoted to Associate Professor of the Practice in 2010, and Professor of the Practice in 2017. Currently, he serves as Associate Dean of Academic Affairs.

Jeanne Pak is a sophomore at Boston University School of Hospitality Administration minoring in Business Administration at Questrom School of Business.

Jeanne Pak is a sophomore at Boston University School of Hospitality Administration minoring in Business Administration at Questrom School of Business.

REFERENCES

-

A Restaurant’s Development into an Institution (1922, October 5). Printer’s Ink, CXXI(1), p. 89.

-

Fallath, R. A. (1977, April 20). Letters – Exchange Buffets – To the Living Section. The New York Times, 55., p. 55.

-

Food Swindler Caught. (1907, August 17). New-York Daily Tribune, LXVII(22,189), p. 4.

-

Grimes, W. (2009). Appetite City: A Culinary History of New York. New York, NY: North Point Press.

-

Haley, A. P. (2011). Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880-1920. Chapel, Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press.

-

Jacob, M. & Benzkofer, S. (2014, July 6). 10 Things you might not know about Chicago restaurants. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved on March 12, 2017 from http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/opinion/commentary/ct-perspec-things-0706-20140706-story.html

-

Mariani, J.F. (2013). Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

-

Popik, B. (2009, June 29). The Big Apple – “Eat ‘em and Beat ‘em” (Exchange Buffet). Retrieved on March 14, 2017, from http://www.barrypopik.com/index.php/new_york_city/entry/eat_em_and_beat_em

-

Ross, G. (1937, July 10). In New York – Others’ Honesty Pays. The Evening gazette (Xenia, Ohio), LVI(163), pp. 6-7.

-

Shanley, J.P. (1963, November 9.) Cafeterias built on honesty fail. The New York Times, CXIII(38, 640), p. 27.

-

Smith, A.F. (ed.) (2015). Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover’s Companion to New York City. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

-

Stockard, W. (1922, February). The “Pay-As-You-Leave” Plan. Hotel Management, 1(1), p. 41.

-

The Trend of Things. (1922). The Financial World, 38(17)

-

True, J. (1922, December 14). Building a Six-Million-Dollar Business on Trust. Printer’s Ink, CXXI(11). pp. 109-113.

-

Whitaker, J. (2004). Quick Lunch. Gastronomica-The Journal of Food and Culture, 4(1), pp. 69-73