BU Students Find Hope at COP29 UN Climate Summit

CAS’ Pamela Templer, Climate Leaders Academy students attended the conference in Baku

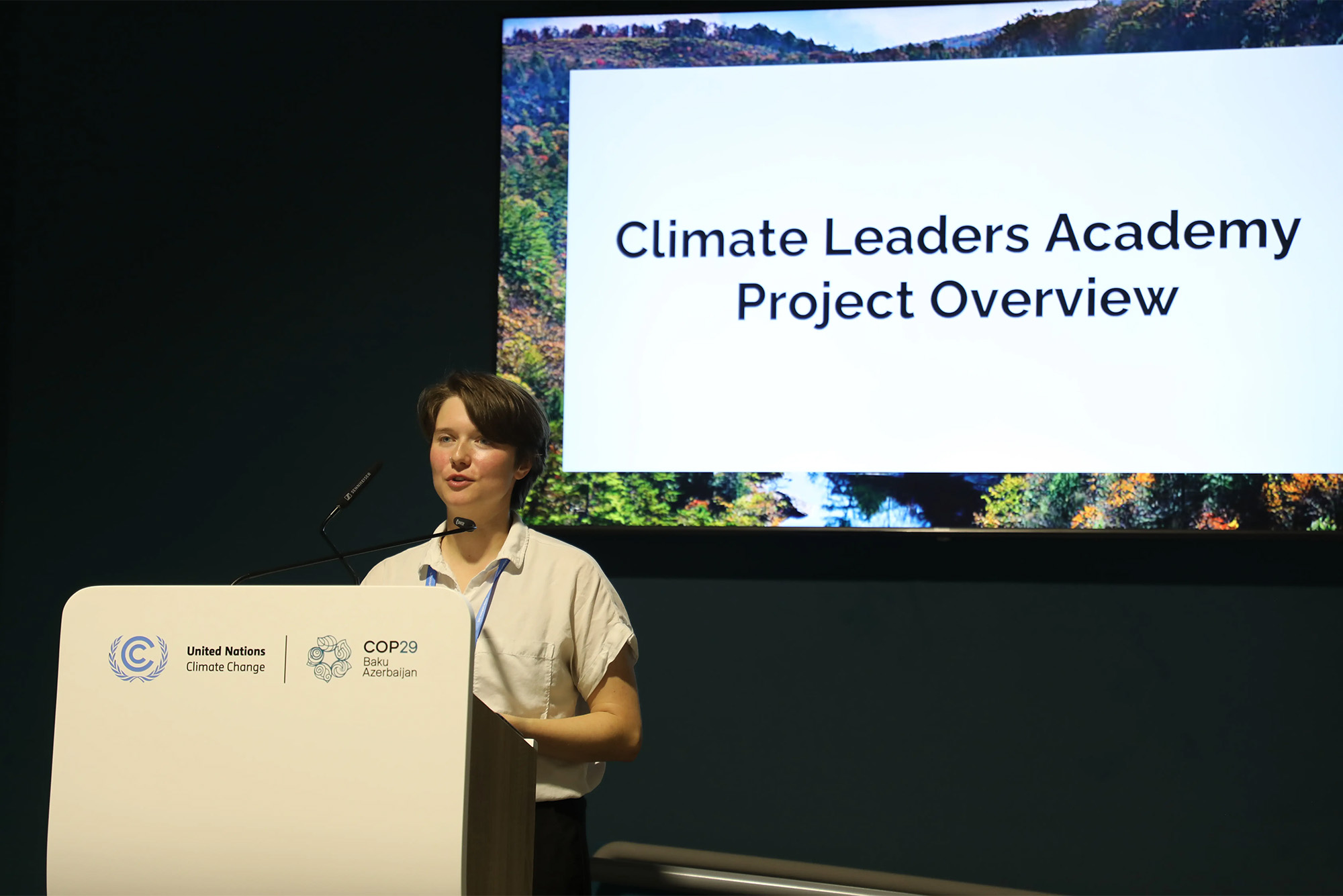

Emma Daily (GRS’28) spoke at a side event at the COP29 climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan, in November. Photo by Jianwei Li

BU Students Find Hope at COP29 UN Climate Summit

CAS’ Pamela Templer, Climate Leaders Academy students attended the conference in Baku

In Baku, Azerbaijan, climate science grad students Emma Daily and Mira Kelly-Fair found reasons to be hopeful about the planet’s future.

Daily (GRS’28) and Kelly-Fair (GRS’22,’27) attended the annual United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP29) international climate summit, held in Baku November 11 to 22. And despite the sometimes contentious discussions, they came home more encouraged than when they left.

“I had a great conversation with some other members of our delegation right before we left Baku,” says Daily. “We talked about our general level of optimism and our outlook on the climate situation that our generation is facing, and we all felt more optimistic leaving COP than we did entering it.”

The 2 were among 15 students from schools around the country who traveled to Baku under the auspices of the Climate Leaders Academy, which trains students in international environmental policy and diplomacy and supports their travel to the annual United Nations Conference of the Parties. The program is co-led by Pamela Templer, a Distinguished Professor and chair of biology in the College of Arts & Sciences. “The whole idea is to train both undergrads and graduate students in environmental science and international environmental policy,” Templer says, “and how the science informs the policy.”

Connecting with other young people from around the world who share a passion for the work “feels like everyone is getting together to do something,” says Daily, who attended the second week of the conference. “Feeling like you can either make a difference or at least witness change is very empowering in some ways, and I felt much more optimistic leaving than I did arriving.”

Kelly-Fair arrived for the first week of what is formally the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) just four days after the U.S. presidential election. The mood was subdued. She says the U.S. delegation made clear that there will need to be more of an emphasis on local and state climate efforts within the United States under a Trump administration. And there’s still not enough funding for everything that needs to be done, she says.

But she also found hope in a surprise talk by former U.S. vice president and environmentalist Al Gore. “He has an infectious energy that just made me feel so much better about what is going on and what needs to be done,” Kelly-Fair says, “and that really was a highlight of COP for me.”

The Climate Leaders Academy students study business, law, education, and other disciplines. The academy is organized through the Youth Environmental Alliance for Higher Education and supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation awarded to Templer and colleagues at Vanderbilt University, Michigan Tech University, and Tennessee State University, some of whom also attended COP29.

“We do this because we want to expose students and train them in international environmental diplomacy, but also to share with them potential career opportunities,” Templer says. “When you go there, you meet people in government, nongovernmental organizations, the private sector, higher education, and it’s just such an open place of communication and collaboration. There’s nothing like bringing students there.”

Daily is a second year PhD biology student in Templer’s lab, largely studying forest biogeochemistry. Currently she’s working on a project about the relationship between urban and rural forests and particulate matter pollution. Kelly-Fair is a third-year PhD student in earth and environment, working with Sucharita Gopal, a CAS professor of earth and environment, focusing on ecosystem services and nature-based solutions, primarily in the mangroves of Belize.

They and 13 other students from universities around the country were chosen in the spring and received six months of in-person and (mostly) online training, and they prepared projects and presentations for COP. “We try to have them participate as much as possible,” Templer says.

Attendees at COP meetings are split into three groups—the actual parties (aka diplomats), the press, and observers, including NGOs and academic researchers, who can participate in side events throughout the conference. Daily and Templer spoke on a panel about intergenerational climate solutions, and Daily and a group of the other students presented on nature-based solutions to climate change.

Kelly-Fair visited pavilions belonging to a number of “SIDS,” or small island developing states, which emphasize how important it is to increase financing to people who are most affected by climate change now.

“My favorite scientist I met was Coral Pasisi—she’s fantastic,” says Kelly-Fair. Pasisi is director of climate change and sustainability for the Sustainable Pacific Consultancy, an international development organization with 27 member countries and territories, primarily island states.

“One issue that we have in the sciences is access to open data. We don’t reward scientists for sharing their data,” Kelly-Fair says, “we reward them for publications. And so it’s very hard to get open access science. And so [Pasisi’s] work right now is focused on creating a website catalog of all the satellite imagery that she can possibly get for the Pacific, and then using that to help people inform their decisions.”

The Climate Leaders Academy students also watched formal and informal negotiations among diplomats that made clear just how difficult it can be to reach global solutions.

One aspect of the process Kelly-Fair followed in Baku was the “technical mechanism,” part of a large global process for sharing information to level the playing field between wealthy developed nations and the less resourced countries that are already bearing the brunt of climate change.

“Basically at this negotiation, the UK and the EU came in and said, ‘We want to scrap that entirely and start reworking.’ And the least developed countries and the African coalition were like, ‘Absolutely not,’” she says.

“The conversations did get pretty frank and honest—and spirited by some countries—which was interesting,” Templer says.

COP29 was held in and around a large soccer stadium and students were put up in the athletes village that was built for the 2015 European Games. In other aspects, it was like any other big convention or trade show. There was plenty of time to explore the old city of Baku and sample the local history and cuisine.

“I got like 30 different pins from all the different [national] pavilions,” Kelly-Fair says. “They give out stuff and free coffee. You’d hear that Turkey had good coffee, so you’d run over to Turkey.”

And that often leads to conversations with people you might not have met otherwise, all three BU attendees say, which is a major side benefit.

“I can give a lecture, you know, online or in a classroom, but it’s nothing like being there and seeing the high level of enthusiasm and energy,” Templer says. “To talk to people, you just talk everywhere. You’re in line to get pizza at lunch. What’s your name? I’m Pam. I’m a professor at BU…”

The Climate Leaders Academy is supported through a three-year grant from the National Science Foundation, which includes funding for a third cohort of students to attend next year’s COP in Brazil. The program will put out a call for new applications in spring 2025.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.