Why Are We So Obsessed with Serial Killers?

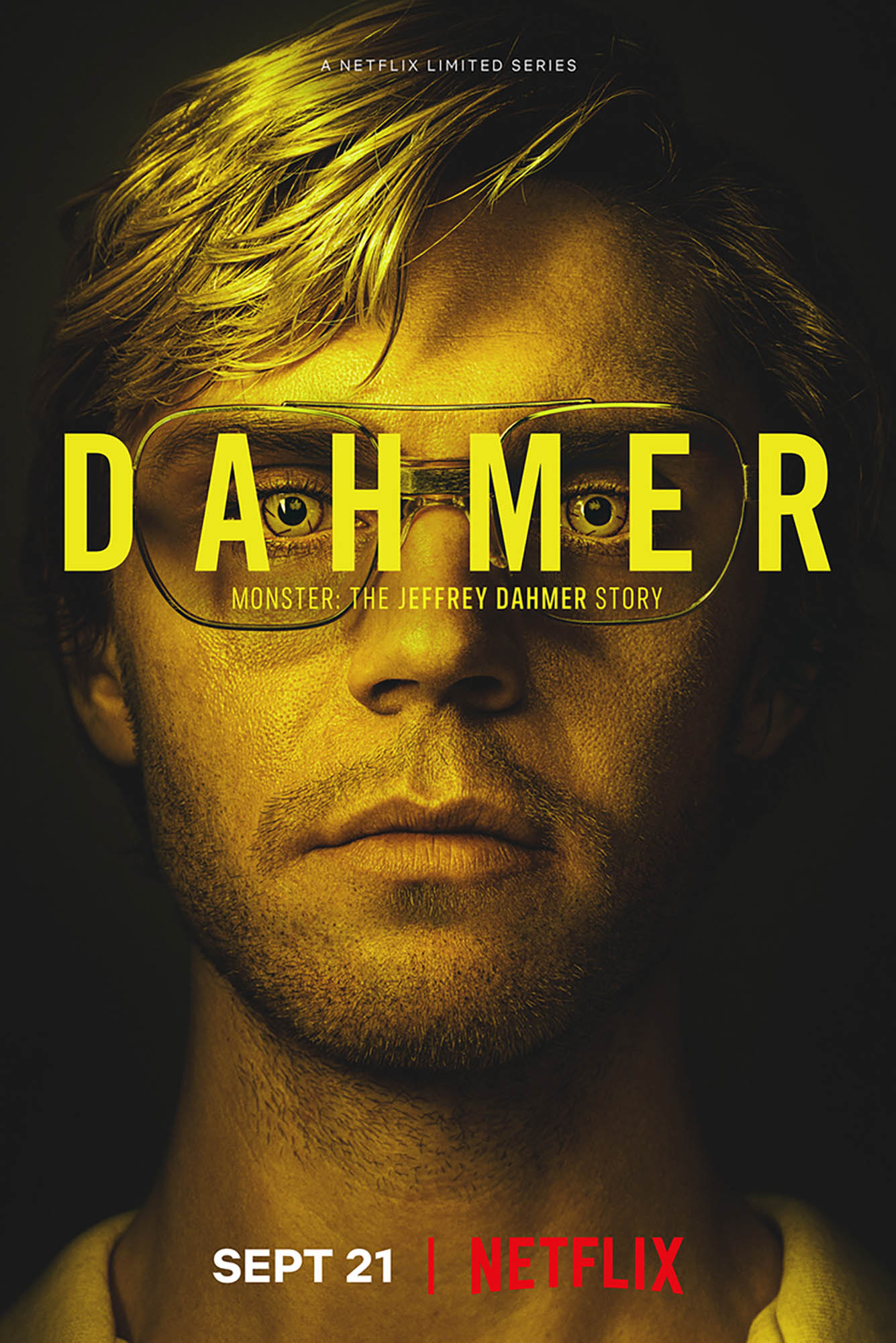

From podcasts to films to TV shows to books to news coverage and more, there’s no shortage of media to provide audiences with stories about serial killers and their victims. DedMityay/iStock

Why Are We So Obsessed with Serial Killers?

Three BU-affiliated experts weigh in on our enduring fascination with true crime’s grisliest stories

Here are the facts: on Friday, July 14, police arrested the man believed to have killed three young women whose bodies were found on Long Island’s Gilgo Beach more than a decade earlier. He is also considered the prime suspect in the slaying of another woman whose remains were identified at the site.

Rex Heuermann’s arrest made international news. But the Gilgo Beach investigation had captivated the true-crime-obsessed public for years, spawning a 2016 docuseries, The Killing Season. The recent headlines introduced a surge of new Gilgo Beach content—all written, directed, and produced since July—complementing a glut of existing podcasts, miniseries, docudramas, and Hollywood biopics about other serial killers.

All of which begs the question: why are we so fascinated by serial killers, and more broadly, by true crime?

Behind media saturation is a healthy dose of audience demand. The Pew Research Center reported in June that true crime is the most popular American podcasting genre, and Reddit’s r/serialkillers page has more than half a million members. There is an innate attraction, buried in the collective psyche, a desire by normal people to crack open cold cases and unspool possible motives.

Deborah Jaramillo, a College of Communication associate professor of film and television studies, says the phenomenon is easy to understand from the perspective of an American audience.

“Our media environment is especially well-suited to creating celebrity and sustaining that celebrity,” says Jaramillo, who teaches a COM course on true crime media. “[We have] this idea of the celebrity criminal, and serial killers kind of turn into celebrities.”

However, Jaramillo says, the phenomenon can be better understood when broken down by race and gender. (Her true crime classes tend to be 90 to 95 percent women, she says.) And Heather Mooney (GRS’22,’22), now a visiting assistant professor at Le Moyne College, agrees. Mooney’s PhD research at BU amounted to a broad ethnography of true crime consumers that had her conducting interviews ranging from YouTube commenters to a reporter for Fox News Crime Stories with Nancy Grace.

“Upwards of 70 percent of true crime consumers, according to Consumer Reports, are heterosexually partnered college-educated women aged 18 to 34 years old,” she says, noting that her own research reached a similar conclusion. “So my biggest question was, why do women consume true crime?

“The biggest answer I got was safety and security—that [true crime media, including content about serial killers], is a form of preventive education that women were using,” Mooney says. “It’s like, how do I learn what the red flags are?”

Kim Overstreet (left), sister of Gilgo Beach murder victim Amber Lynn Costello (right), kneeling at her sister’s memorial site on Ocean Parkway, near where her remains were recovered. Photo by Mary Altaffer/AP

Jaramillo says that among her students, bonding over true crime also builds a sense of community. “The way that my class relates to true crime and to each other, there’s a solidarity there,” she says. “There’s something about listening and watching that puts you in solidarity with other women who, through no fault of their own, wound up victimized by someone.”

Mooney’s research found that a viewer’s race and gender may help explain which true crimes they’re drawn to. Women of color—particularly Black women—tend to focus on unsolved crimes that were impacting their communities.

“With the Black women that I spoke to, it was more like, these cases are not being covered by the mainstream media. Missing White Woman Syndrome was something that came up a lot,” she says. “To them, it’s like, we need to know what this girl was wearing, where she was going, where she was last seen, in order to make sure that we can find her. There’s this collective sense that police aren’t going to, so [they] want to be [their] own protectors and spread this information.”

As for male interest in true crime and serial killers, Mooney says, the men she spoke to were primarily interested in the genre out of a desire to be a protector. “They were like, this is why I carry a gun—because I need to know how to defend my girlfriend, my sister, my wife, my kids,” she says. “A lot of people, mainly men, become interested in fields like criminal justice and prelaw because of stories about serial killers—they’re a really powerful access point.”

And then there is the brain-tingling stimulation these stories provide. Mooney reported that a number of her interviewees spoke of putting on a podcast or true crime shows such as Don’t F**k with Cats to keep themselves engaged while performing domestic tasks like laundry.

These stories are thrilling, and sometimes titillating, but they also contain “that level of authenticity that murder, and trauma, can create,” according to Jaramillo. “For some, it’s not about the serial killer itself, but the emotion, and the realness, of the crime.”

And stories like these don’t just give insight into what’s interesting, even fascinating, to us—they can also tap into what we fear.

“These ideas, that there are these people lurking out there, support everyday people’s tendency toward a culture of control,” says Heather Schoenfeld, a CAS associate professor and chair of sociology. “We don’t have much control over our socioeconomic or racial status, or whether our kids have the resources they need—but we can make sure they don’t walk to the bus stop by themselves.”

These kinds of stories] “support this culture of control, Schoenfeld says, whether it’s in our own individual lives or in our support for a harsh criminal justice system—ultimately, I think it’s not a great thing.”

Mooney is an unabashed true crime fan, and while she is well aware of the genre’s limitations, she is also aware of its potential. When storytellers focus more on the victims and their families and less on the killers themselves, a different kind of narrative begins to unfold.

True crime stories “are valuable because they tell us about our history—they’re literally ghosts that haunt us,” she says. “We have an opportunity, when we look at these serial killers, to tell the story in a way that isn’t so individualistic, but to contextualize it in a bigger history of power and inequality.

“What kind of world do we want? How can we leverage this media and sources to think about things a little bit differently?”

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.