Neal Boudette, Veteran Auto Industry Reporter, on the Historic Auto Workers Strike

Neal Boudette parses the first-ever simultaneous walkout on the Big Three

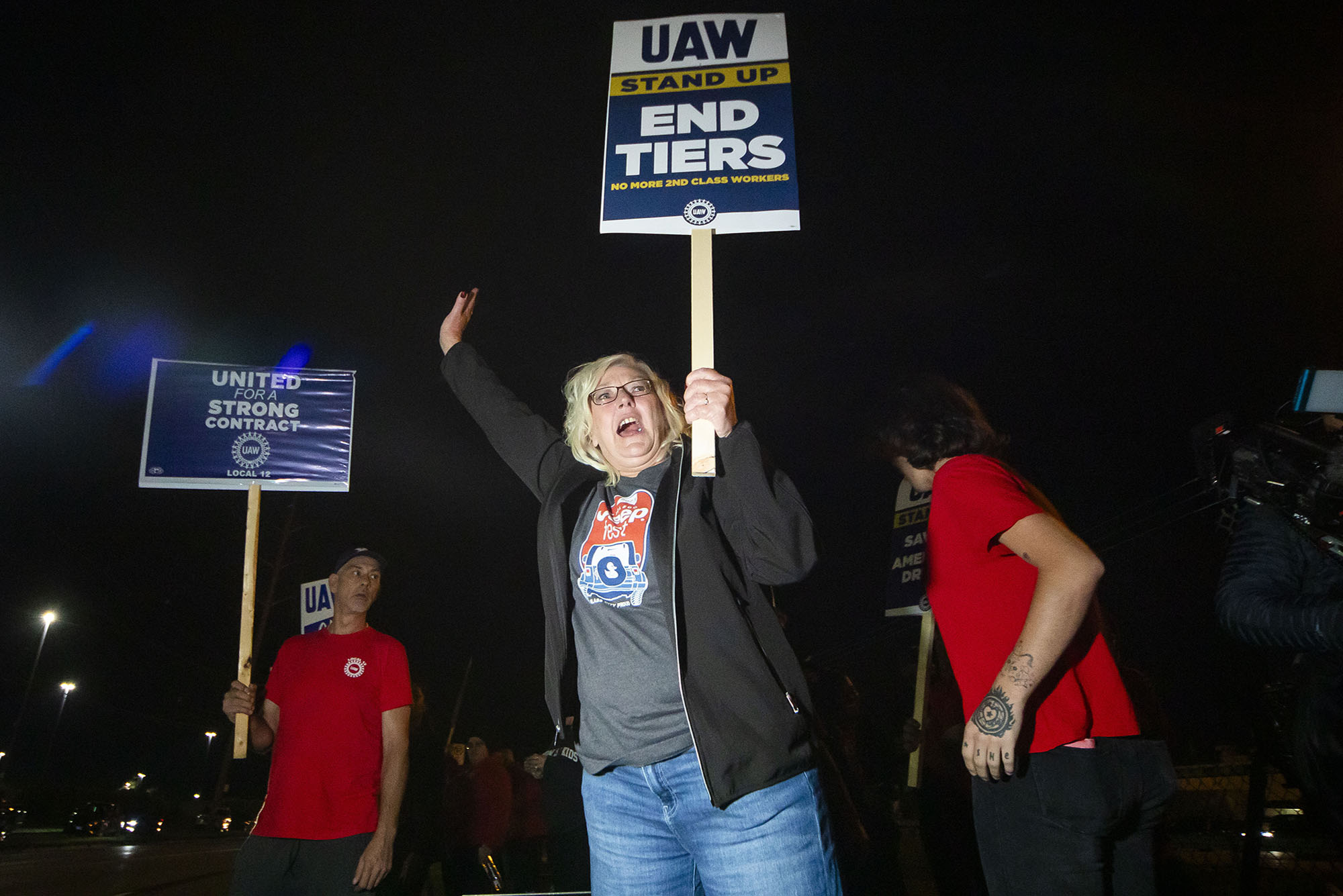

Striking auto workers may have targeted just three plants, including this Stellantis one in Toledo, but it’s the first simultaneous walkout against all Big Three US carmakers. Photo by Katy Kildee /Detroit News via AP

Veteran Auto Industry Reporter, and COM Alum, on the Historic Auto Workers Strike

Neal Boudette parses the first-ever simultaneous walkout on the Big Three

The United Auto Workers is staging the first-ever simultaneous strike against the Big Three automakers. While historic in the scope of companies involved, the union’s stoppage is precision-surgical in reach, targeting just three plants: GM’s assembly plant in Wentzville, Mo., Ford’s assembly and paint plant in Wayne, Mich., and Stellantis’ assembly plant in Toledo, Ohio. Negotiations for a new contract between the union and manufacturers stalled Thursday over differences regarding wages, pensions, and working conditions.

New York Times reporter Neal E. Boudette (COM’84), who has covered the industry for 20 years, was interviewing strikers outside the Ford plant Friday, when Bostonia reached him to parse the historic labor dispute.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Q&A

with Neal E. Boudette

Bostonia: GM and Ford offered 20 percent pay raises. That’s less than the 36 percent the UAW is looking for, but probably sounds generous to workers in other industries. Is it likely that a final settlement will take the form of the classic split-the-difference?

Neal E. Boudette: I think in the end, they will come down somewhere in the middle on wages. But there are many other issues that are much harder to solve and will take a lot more negotiating.

They have this tiered wage system, where people who were hired before 2007 are at the top wage of $32 an hour. People hired today come in at $16.67 an hour. You can have these people doing the same work, making almost half of what your colleague’s making, and you have to work eight years to climb to the top of the UAW wage. The UAW wants to move everybody to $32 over 90 days. Ford and GM offered to change the grow-in period to four years instead of eight. But the companies are cautious, because most workers are not at the top wage, so that would increase costs for them considerably.

Then, the workers want to have the ability to strike when plants close. They’re concerned that as companies make more electric vehicles, there will be fewer workers and they’ll close plants. So they want to have some way of pressuring the companies to keep plants and production in the United States. They’ve also asked for the companies to start paying for retiree health care coverage. That ended in 2007. The companies do not want to get back into that. That is a major cost and burden on their books.

Bostonia: The union also wants a return to traditional pensions. In today’s economy, is that realistic?

Neil E. Boudette: I think that is another issue the companies are going to resist. Most companies offer 401(k)s. [Traditional pensions are] another defined benefit that could have long-term costs; people are living longer, and so you don’t really know how much that is going to cost the company in the end. With a 401(k), the company puts money in, the person retires, and the company is not continuing to support them. I suspect, in the end, the union will probably relent on that.

There’s negotiating going on here. They ask for the moon, and then they settle for halfway to the moon. That’s why they put out that demand for a four-day workweek—work four days and get paid for five. They want to highlight workers who are required to work six days a week, sometimes even seven, and often 10, 12 hours a day. The manufacturers can decide a plant is on critical status—let’s say, it makes a vehicle that’s super-popular and profitable, and they just have to run it around the clock, and they say to the workers, I’m sorry, but this plant’s on critical status. Stellantis has a number of plants on critical status.

Union President Shawn Fain says work-life balance is not only for the managerial class. When you’re making $20 an hour and you’ve got two kids and they’re going to go to college, if you’re working 40-hour weeks, that’s about $40,000 a year—if you live in the Boston area, you’re not going to live in Winchester on that. Or Back Bay, Brookline, or probably these days, Somerville or Revere. He’s trying to get some relief by asking for something out of reach that maybe the manufacturers will give [some] on.

There’s negotiating going on here. They ask for the moon, and then they settle for halfway to the moon.

Bostonia: In recent years, the automobile manufacturers have been fairly flush. But they are afraid of nonunion, cost-advantaged competitors like Tesla. Do those competitors pose an existential threat to the Big Three?

Yeah, it does seem to be a little bit of a disconnect, doesn’t it? There are pressures, yet you’re making record profits; makes you kind of want to go, huh? [During the 2008 financial crisis] GM and Chrysler [today Stellantis] were reorganized in bankruptcy, led by the government. But these days, they’re making money that was unimaginable before. GM last year made almost $10 billion; years ago, that would have knocked you over. Stellantis made about $12 billion in the first six months of the year. They’re benefiting from Americans buying trucks and SUVs, which have higher prices and profit margins. Also, because of the computer chip shortages, they haven’t been able to make as many cars as people were willing to buy, and it’s the law of supply and demand: there are more people looking to buy cars than cars available, so everybody is paying sticker, or sometimes above, sticker price.

Bostonia: Are the UAW’s demands sustainable long-term for the companies?

It’s hard to tell. Ten years ago, people thought China, Russia, Brazil, and India were going to be massive auto markets. Russia obviously is a disaster. Brazil—their economic situation, their political situation—disaster. India just has not panned out. China, while it’s a huge market, [has] so many competitors that there are not the kinds of profits that were there. Ten years ago, it looked like growth from these giant countries, but it didn’t pan out.

And the same thing could happen here. It’s hard to say whether these profits for the Big Three will continue. One of their other concerns is they’re investing tens of billions in electric vehicles, and they need a lot of profit to plow into R & D. They have to develop the vehicles, build battery plants, retool existing plants.

Bostonia: It sounds like you’re facing a long stretch on the sidewalk interviewing strikers?

Yeah, I think this could go on for a while. In 2019, the union was out 40 days against General Motors. Here, it’s a narrower, targeted strike. I think it’s very shrewd on UAW’s part to do it this way. The GM plant in Missouri makes the Chevy Colorado and GMC Canyon; they’re very profitable, popular. The [Stellantis] plant makes the Jeep Gladiator and other Jeep vehicles. Again, popular and profitable. So the companies are going to feel it from this stoppage, but it limits the impact to other constituencies. If they went out on strike on everybody, it would hurt the Midwest economy, the US economy. There would be other people put out of work, and they would be mad at the UAW. What are you complaining about? You’re getting 20 percent.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.