What Will Bruce Willis’ Aphasia Diagnosis Mean for the Veteran Actor?

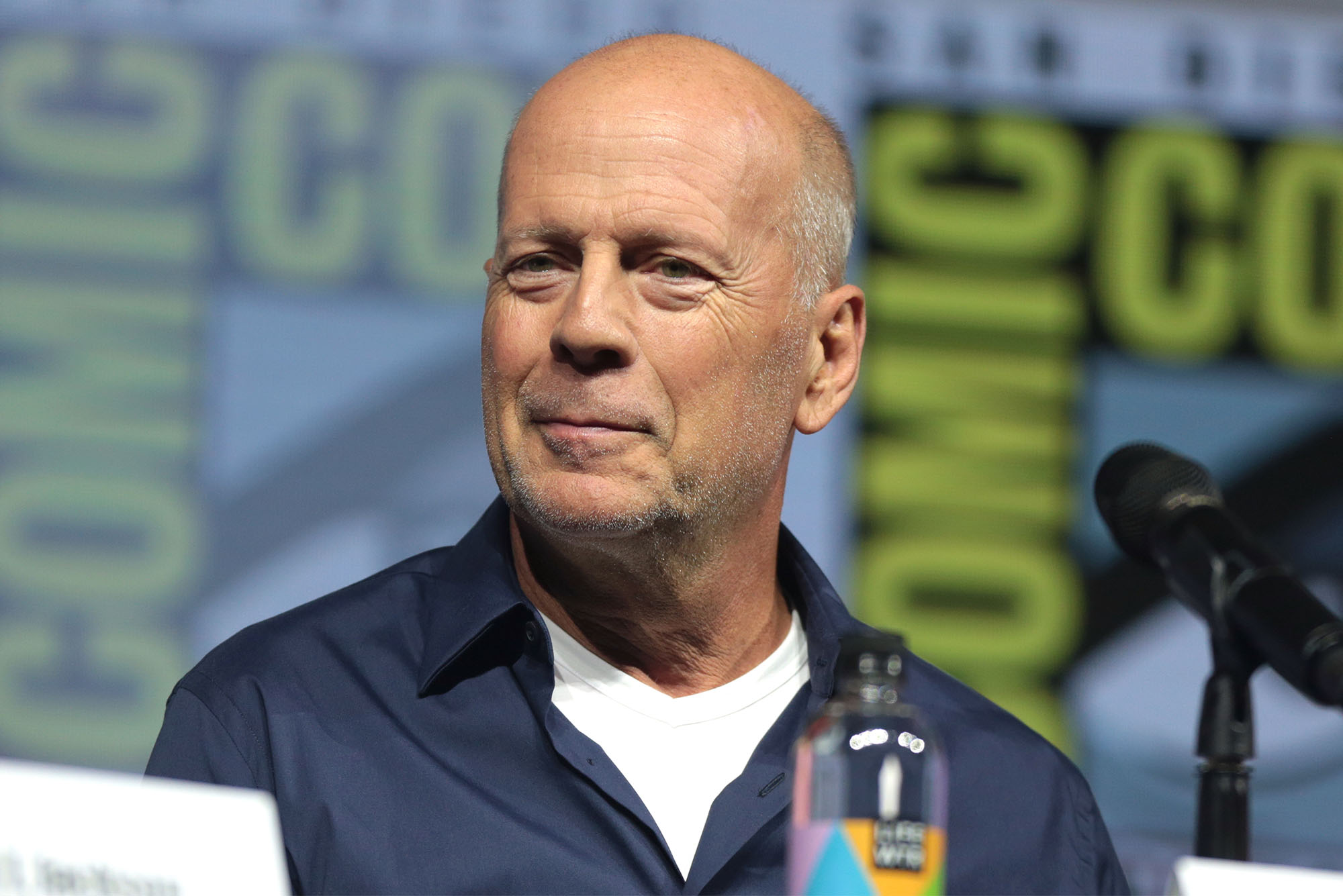

Photo by Gage Skidmore

What Will Bruce Willis’ Aphasia Diagnosis Mean for the Veteran Actor?

Swathi Kiran and Elizabeth Hoover of BU’s Aphasia Resource Center explain the neurological disorder and what lies ahead for the Die Hard star

An unwritten rule of action movies is that you should never count out the hero, no matter how dire the straits they’re in. Fans of Bruce Willis, star of the Die Hard franchise, The Sixth Sense, and Pulp Fiction (among many, many other movies), hope the 67-year-old actor has one more fight in him. In coordinated statements posted to Instagram, members of Willis’ family, including ex-wife Demi Moore and daughter Rumer, recently announced that the action star had been diagnosed with aphasia, a neurological disorder, and would step away from acting.

“This is a really challenging time for our family and we are so appreciative of your continued love, compassion and support,” Moore wrote in her post. Tributes from Willis’ fans and fellow actors poured in, celebrating an icon of American cinema whose body of work spans more than 40 years.

For many, it was their first time hearing about the condition, leaving lots of unanswered questions: What, exactly, is aphasia? How does it manifest and is it treatable? Will Willis ever appear on screen again?

For answers, The Brink turned to two experts from Boston University’s College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College, which is nationally renowned for its aphasia research and treatment programs: Swathi Kiran, director of BU’s Aphasia Research Laboratory and a professor of neurorehabilitation, and Elizabeth Hoover, clinical director of BU’s Aphasia Resource Center (where Kiran is research director) and a clinical professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences. The Aphasia Research Laboratory aims to better understand language processing and communication following brain damage, while the Aphasia Resource Center offers free weekly group and individual treatments and support meetings to dozens of individuals (and their families) living with a condition that is less rare than you might think.

Q&A

With Swathi Kiran and Elizabeth Hoover

The Brink: As concisely as you can explain it, what is aphasia?

Hoover: Aphasia is defined as a language disorder that results from damage to areas of the brain that control how we formulate and how we understand language. It’s a far more common condition than most people realize. Conservative estimates say that 2.5 million people in America are living with aphasia, which is more common than Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, and ALS combined. Importantly, aphasia, because it disrupts how we understand and how we express language—both spoken and in writing—affects how we communicate. Communication is central to how we share our stories in the world and how we interact with other people. One of the big misconceptions about aphasia is that it impacts cognition—the way somebody thinks. Aphasia is a language disorder, not an intellectual disorder.

The Brink: What causes aphasia?

Kiran: In most cases, the cause of aphasia is stroke or hemorrhage to the brain. It’s something that’s a sudden onset, an acquired brain event, and one-third of all stroke survivors end up having aphasia. Another sudden onset is that somebody’s in a car accident and has a traumatic brain injury. Another cause is in people who have tumors, and they end up having aphasia. A different cause is when the symptoms worsen over time; they start with language problems, and it’s a gradual change that happens over time. That particular condition is called primary progressive aphasia. In that case, by the time the disease progresses over the years, the person will end up having cognitive effects as well, like dementia.

With stroke aphasia it’s easier to know the cause, because somebody has a sudden event of the brain and usually a neurologist can diagnose that when they look at a brain scan. In primary progressive aphasia, since it’s a neurodegenerative disease, we don’t fully know what causes it. What usually happens is that the symptoms precede the diagnosis, because the person notices the symptoms and they worsen over time.

The Brink: Do we know how Willis developed aphasia and which type he has?

Kiran: Based on the little information that has been released, we don’t know if he has had a stroke or if he has not had a stroke. It’s hard to comment on that. What’s clear for us to say is what he is going through right now.

The Brink: What is Willis likely going through, and why would someone with aphasia need to step away from a career in movies, as his family has announced he is doing?

Hoover: If you think about language and how language is used by an actor, it’s easy to see why aphasia would pose a challenge. The core feature of every profile of aphasia is this difficulty with word retrieval. It’s also called anomia. That can present with hesitancies, latencies, or errors in being able to produce that word. It might be difficult to read or understand scripts, speak with fluency, and understand what your fellow actors are saying.

The Brink: How do we treat aphasia? Is there a cure?

Kiran: Unfortunately, there is no cure for aphasia. Fortunately, traditional treatments for aphasia are proven to be quite effective: traditional speech-language therapy, which involves one-on-one interaction with a therapist; just practicing and exercising drills every day has been shown to be quite clinically significant in terms of improving outcomes. People who receive therapy go on to lead successful, happy lives. It’s a long road to recovery, but the brain, especially after a stroke or a hemorrhage, is quite plastic, and rehabilitation harnesses that plasticity. This is also true in the cases of primary progressive aphasia where the condition declines over time. There’s promising new data being published showing that such structured rehabilitation can slow the disease down or even stall it.

The Brink: BU is home to one of the world’s leading centers for studying aphasia and supporting those who have it. Tell me about your research and if you’ve seen any promising developments in terms of improving diagnoses and treatments for individuals with aphasia.

Kiran: The research we do is about harnessing that neuroplasticity. I think the most important thing that we’re trying to find out and understand is how much recovery a person can have right after their stroke—which is actually a lot. Many people fully recover a few months after a stroke. And even if they didn’t, how much plasticity can be enabled through this rehabilitation as time goes by—and by time, I mean months and years—after the stroke. The brain needs a lot of repetition to learn, and the brain needs a lot more repetition to relearn. So, therapy can come in the form of one-on-one therapy and group therapy, and I’ve been involved in developing a software program at BU [Constant Therapy], where patients can download it on their phone and practice at home and still get a lot of therapy.

A lot of the one-on-one rehabilitation work is being done at BU, and we’re probably one of the most well-known rehabilitation centers that do this systematic, rigorous therapy for stroke survivors in the country. Our program is very well-regarded. And [rehabilitation] is currently the only way people can improve their abilities.

The Brink: Where would you start with Willis and his family, were they to walk into the Aphasia Resource Center?

Hoover: It starts with a really comprehensive evaluation looking at their individual profile of language communication difficulty, looking at the impact of the aphasia on their quality of life, so that we can understand the nuances of their profile. And then sitting down with them and looking at those meaningful goals. It’s about trying to build that critical amount of therapy, so looking at scheduling that individual therapy—again, nuanced and individualized for their goals—but also adding in some communication programming via the group treatments, and then certainly support groups for the caregivers and communication partner training. It’s about building this critical program that’s as intense as possible that will meet that minimum amount of practice. Finally, the Constant Therapy app and other computerized programs really will help boost that additional practice over the course of the week.

The Brink: Can you say more about the support you give to caretakers of individuals living with aphasia?

Kiran: The kind of support people need is very different at various points of the diagnosis and journey. Right after the diagnosis, it’s tremendously overwhelming and devastating for the loved one, as well as for the family members. They are continually overwhelmed by the number of things they realize they cannot do now. And for that reason, they need a lot of immediate support, like, how do I help my loved one communicate their basic needs? Then there’s grieving and getting over the loss of this independence that the person has. And then, as time goes by, it’s a sort of acceptance of what’s happening in their life. Now, how do I live successfully and make the best out of it?

The Brink: Will we ever see Willis on screen again?

Hoover: I hope so. I think it depends on his comfort with his language and on what type of a role he might want to play. From a personal perspective—and this is my opinion—one of the reasons that aphasia is so poorly understood and so poorly known in the public is because we don’t have a spokesperson. We don’t have the Michael J. Fox or the Muhammad Ali who’s out there saying, “This is what this condition is, and here’s how I’m living successfully with it.” I wonder if one of the reasons we haven’t had a spokesperson up until now is because there’s often some misconceptions about struggles with language, and these struggles are linked to cognition and intellect. I would love to see somebody brave enough to share their experiences of aphasia to the public and hopefully destigmatize it in that way.

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.