Robert A. Brown, BU’s 10th President, to Retire after 2022–23 School Year

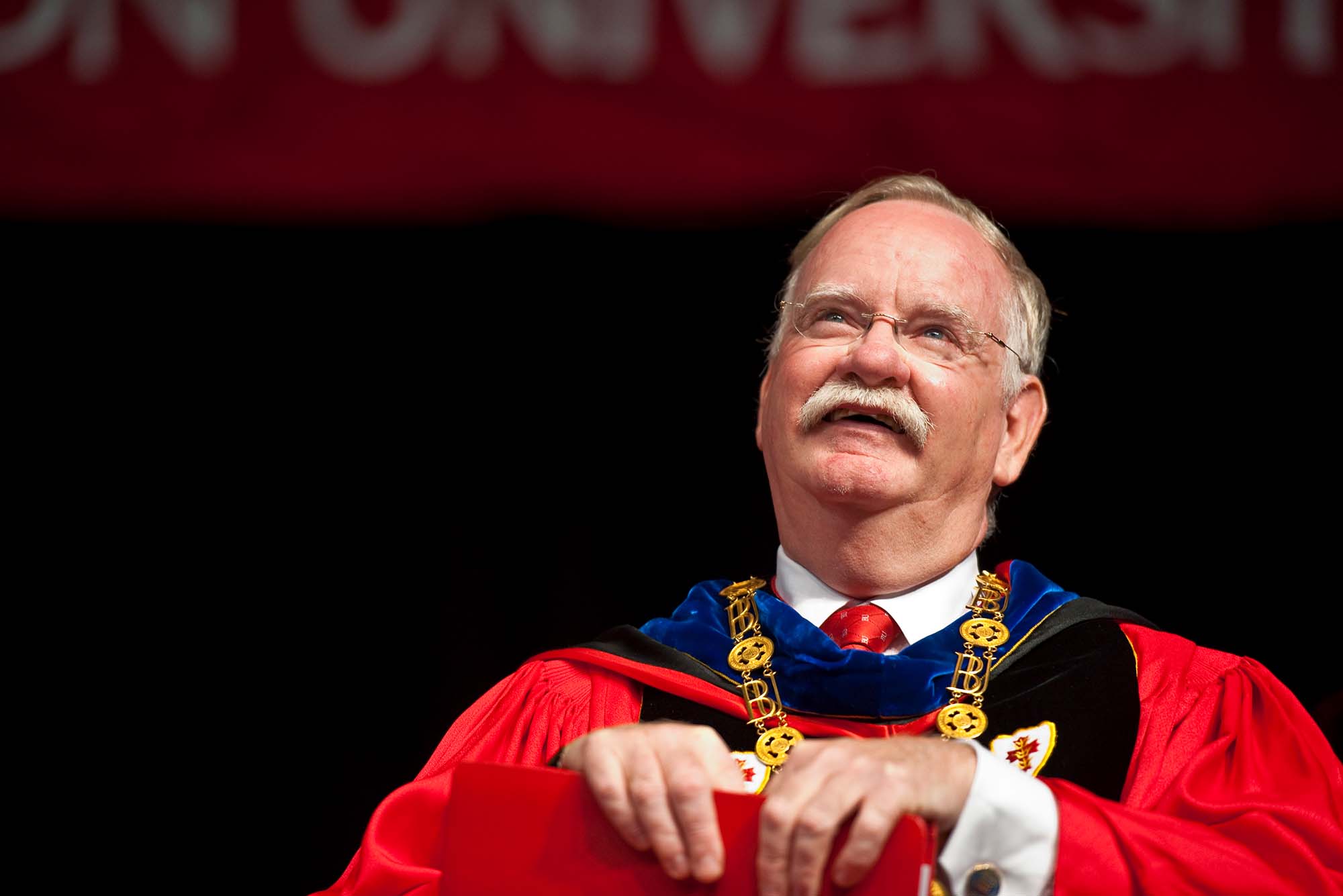

BU President Robert A. Brown welcoming parents and students of the Class of 2014 at Matriculation, August 29, 2010. Photo by Melody Komyerov

Robert A. Brown, BU’s 10th President, to Retire after 2022–2023 School Year

His 18-year legacy includes dramatic growth in sponsored research, a more diverse student body and faculty, a robust endowment, a campus that proudly embraces its relationship with Boston, an exciting new building for data science—and a clear path for the future

“His fingerprints will be on BU for a long, long time.”

—Martin Walsh, former Boston mayor

Robert A. Brown, Boston University’s 10th president, who steered the school to become a more diverse, accessible, and academically rigorous leading private urban research institution, has announced he will step down at the end of the 2022-23 academic year.

“Rather than stay on for another 18 months or two years, I just came to the conclusion that this was the right time,” Brown says in a lengthy interview reflecting on his tenure. In the letter he sent to the BU community on Wednesday, he wrote: “Boston University is an astonishing community of faculty, staff, and students. Helping lead Boston University has been the most fulfilling work of my professional career.”

Brown, who turned 71 in July 2022 and whose contract was set to run through 2025, began his presidency in September 2005. He leaves behind a nearly two-decade legacy of transformative change for the largest higher education institution—public or private—in Massachusetts. By encouraging greater collaboration across BU’s 17 schools and colleges to take on global crises, from climate change to infectious diseases to mental health to racism, Brown lifted the University to new heights. Among his major achievements are leading the school’s first-ever comprehensive fundraising campaign ($1.8 billion) and gaining BU’s 2012 acceptance into the Association of American Universities (AAU), a group of 65 public and private universities, from Harvard to MIT to Northwestern to Duke, considered on the leading edge of innovation and scientific research.

“The AAU is the gold standard, the external validation of a school’s accomplishments as a research institution,” says Jean Morrison, BU provost and chief academic officer, who was appointed by Brown in 2010. “It was a focus for Bob, and I was in his office when he got the call. It was what he envisioned as among the most important achievements for us.”

A quiet leader who prefers working from behind the stage curtain rather than in front of it, when it comes to BU’s community, Brown wanted the student body to be of higher caliber, and prioritized recruiting more prominent faculty focused on research and scholarship, as well as teaching. He has also emphasized the importance of interdisciplinary research, pay equity, and diversity when it comes to new hires.

Brown with graduating students before the start of Senior Breakfast at the Metcalf Ballroom May 6, 2011. Photo by Cydney Scott

Brown with graduating students at Senior Breakfast at the Metcalf Ballroom May 6, 2011. Photo by Cydney Scott

“He empowered the faculty in unprecedented ways,” Kenneth Feld (Questrom’70), Board of Trustees chair, and Ahmass Fakahany (Questrom’79), chair-elect, wrote in a letter to the BU community after Brown’s announcement. “He enabled and encouraged them to pursue research and creative work in ways that are consistent with the best AAU universities. He brought the best of higher education management principles to BU, applied them in consistent, creative, and ambitious ways. In doing so, he transformed the University into one of the leading urban research and teaching institutions in the world today.” Their letter added that they had been talking with Brown about the “appropriate time to consider a leadership change,” and with the framework of BU’s 2030 Strategic Plan done, “Bob felt we were at the right juncture to plan for his successor.”

At a time when the country has become so divided politically, Brown has supported free and healthy dialogue on campus, even when it meant allowing controversial speakers he knew would spark protests and ignite debate. He pushed for BU to become more inclusive, dramatically expanding the Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground, creating a new senior diversity officer position, and opening a center dedicated to helping first-generation college students adapt to college life, a mission that was deeply personal to him. And after years of prodding from students and climate activists, Brown announced in 2021 that BU would divest from the fossil fuel industry, and he credited advocates who pushed for the change.

A native of San Antonio, Tex., Brown is a first-generation college graduate himself, earning an undergraduate degree in chemical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin and a PhD in chemical engineering from the University of Minnesota. As University president, he has prioritized admitting more undergraduates with Pell Grants and providing greater financial aid to make BU more accessible at a time when the soaring costs and rising competitiveness of higher education have come under increasing scrutiny.

“One of the things I’m proud of, that I did not think back in 2005 would be a big agenda item, is how we’ve been able to, with resources and with changes, diversify the student body, not only racially and ethnically, but also socioeconomically,” Brown says. In his announcement letter, he wrote that he was “most proud of our large commitment to undergraduate student need-based financial aid and its impact on the diversity of our student body.” This fall’s domestic freshman class, he wrote, consists of 25 percent Pell Grant recipients, 25 percent first-generation students, and 33 percent underrepresented minority students.

As the University’s endowment increased from approximately $700 million to more than $3 billion under Brown, its Charles River Campus erupted with new construction. The StuVi 2 student residence, the sleek Rajen Kilachand Center for Integrated Life Sciences & Engineering, the larger and more visible Thurman Center for Common Ground, the new glass front of the College of Fine Arts, the expansion of the Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine, and the striking Joan & Edgar Booth Theatre all occurred on Brown’s watch. And a donation from New Balance made possible the 110,000-square-foot New Balance Field on West Campus, an exciting green space for women’s field hockey as well as for thousands of students who play intramural and club sports. Across town, on the BU Medical Campus, the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL) opened in 2014, becoming a global leader in the fight against some of the world’s deadliest diseases, from Ebola to Marburg virus to COVID-19 (one of NEIDL’s most prominent leaders, Nahid Bhadelia, a School of Medicine associate professor, is now serving as a White House advisor on infectious diseases).

One final crowning moment of Brown’s tenure came in December 2022—the opening of the 19-story Center for Computing & Data Sciences, a towering building resembling an off-center stack of books, which will house the new Faculty of Computing & Data Sciences. (It is powered by underground geothermal wells and is 100 percent free of fossil fuels, a point of pride for Brown). Winning approval for such a dramatic-looking, environmentally friendly building on Commonwealth Avenue, one of Boston’s busiest thoroughfares, is a testament to the close relationship Brown forged over the years with Boston’s mayors—from the late Thomas Menino (Hon.’01) to Martin Walsh to Kim Janey to the current administration of Michelle Wu.

Brown giving Boston Mayor Michelle Wu a tour in May 2022 of the soon-to-be finished 100 percent fossil fuel–free Center for Computing & Data Sciences. Photo by John Wilcox, Boston mayor’s office

Brown giving Boston Mayor Michelle Wu a tour in May 2022 of the soon-to-be finished 100 percent fossil fuel–free Center for Computing & Data Sciences. Photo by John Wilcox, Boston mayor’s office

Of those mayors, Brown worked the longest with Menino and with Walsh, his successor, who later served for two years as US Secretary of Labor under President Biden. Asked to reflect on one memorable interaction he had with Brown back when he was mayor, Walsh did not hesitate.

“The building,” he says with a laugh, referring to the Center for Computing & Data Sciences. “He came to me and said he wanted to talk about this building. He said the design is unique. I thought, okay, that’s fine, we are changing the culture in Boston, we don’t want just another box building. Then he comes in with some kind of model or representation of it. I looked at it, and I said, ‘Well, that’s certainly different!’”

But Walsh, now the executive director of the National Hockey League Players’ Association, could tell how proud Brown was of the design. “It was iconic,” Walsh says. “And the mission of the building is important. And it’s one of the cleanest, greenest buildings in the country. That meeting was funny. He was giddy about it. But his legacy won’t just be that building, it will be the whole campus of BU. His fingerprints will be on BU for a long, long time. I’m honored to have served alongside him for all those years.”

Brown acknowledges that the changes to the campus that he helped drive are a point of pride for him.

“One of my goals when I think physically about the campus was for us to face into the city, and not face the Charles River,” he says. “When I came here, there were a lot of parking lots on Commonwealth Ave. They’re almost all gone, and they’ve been replaced by inspiring buildings. We are an urban university. I have always used that word, all the way back to my inauguration. Urban. Because we interface with the city and being in the city is a major part of who we are, why students come here, how we interact collectively with our surroundings, and much of the best research that we do.”

Building an academic and research powerhouse

Perhaps not surprisingly, given Brown’s background in research (in 2008, he was named one of the top 100 Chemical Engineers of the Modern Era by the American Institute of Chemical Engineers), the University has grown across multiple science and engineering disciplines, the biggest being the creation of the Kilachand Center for Integrated Life Sciences & Engineering, which opened in 2017 with support from a $115 million donation from Rajen Kilachand (Questrom’74, Hon.’14), a BU trustee. A few years prior, the Rafik B. Hariri Institute for Computing and Computational Science & Engineering was started as the University began to expand its footprint in these disciplines.

Brown believes the work being done at those centers, and others, is not only worthy of his praise, but that it deserves recognition outside of BU. Some of that recognition comes in the form of sponsored research awards to faculty, which jumped under Brown, from $305 million in 2005 to $531 million last year. But membership in the AAU was what he wanted most.

“Our rising research expenditures are a validation of the quality of our STEM faculty,” he says. “Because the AAU admits people on the basis of data, measuring how intensive your research university is, the impact of the research by our faculty, and the publications produced by this research. So yes, it’s great to be the president of an AAU university, but most important is the validation of the quality of our faculty.”

Cutting the ceremonial ribbon to open the Kilachand Center for Integrated Life Sciences and Engineering, September 14, 2017. Photo by Cydney Scott

Cutting the ceremonial ribbon to open the Kilachand Center for Integrated Life Sciences & Engineering, September 14, 2017: Gloria Waters, VP and associate provost (from left), Brown, Rajen Kilachand (Questrom’74, Hon.’14), Boston Mayor Martin Walsh, and Kenneth Feld (Questrom’70), Board of Trustees chair. Photo by Cydney Scott

Gloria Waters, BU vice president and associate provost for research, says for her, Brown’s emphasis on getting departments and schools to work with one another, rather than in silos, has been especially important. “I think what is most impressive is the range of collaborations taking place—with almost every school and college, with basic scientists, social scientists, and even those in the humanities,” Waters says.

She points to certain centers in particular, because of how quickly they grew and collaborated across campus, such as the Neurophotonics Center, the Global Development Policy Center, and the revised Institute for Sustainable Energy, which emerged because of the wide range of faculty whose work focuses on topics related to sustainability.

One center in particular that has brought BU national prominence is the School of Medicine’s Traumatic Encephalopathy Center (CTE), which opened in 2008. Through its research on head trauma under director Ann McKee, a MED professor of neurology and pathology, the CTE has linked concussions to depression and dementia in athletes and soldiers, and has directly led to significant rule changes in the National Football League and other professional sports.

That same year saw the late Osamu Shimomura (Hon.’10), a MED professor emeritus of physiology, honored, along with two others, with the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for groundbreaking research on the discovery and application of fluorescent proteins.

Beyond the sciences and engineering, however, Brown’s support for the humanities and social sciences is also vigorous. The recruitment of Ibram X. Kendi, an acclaimed scholar and rising star in antiracism research, to establish the Center for Antiracist Research in 2020 positioned BU at the forefront of a pivotal issue at a time when attacks by police and others against the Black community and other minorities were surging. Both Kendi—BU’s Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities and a College of Arts & Sciences history professor—and the center have garnered widespread attention for pointing a spotlight on societal inequities based on race.

The 2011 opening of the Arvind & Chandan Nandlal Kilachand Honors College was seen as another step in providing more challenging academic opportunities for students. And the launching of the BU Hub for incoming freshmen in 2018 was aimed at educating all undergraduates, “no matter their major, to develop intellectual capacities that will teach them to thrive throughout their lives.”

It was also Brown who pushed for the 2018 merger of Wheelock College with BU’s School of Education, creating the new Wheelock College of Education & Human Development. The strategy was to breathe new life into the mission of training a new generation of scholars and teachers to pursue community-building, equity, and justice-oriented outcomes in K-12 education, especially in an urban environment.

Azer Bestavros, Provost Jean Morrison and President Brown as the final beam (at center) is put in place during the September 30, 2021 topping-off ceremony at the Center for Computing & Data Sciences.

A view of the Center for Computing & Data Sciences from the BU Bridge July 8, 2022.

Azer Bestavros (from left), associate provost, Jean Morrison, provost, and Brown as the final beam (center) is put in place during the September 30, 2021, topping-off ceremony for the Center for Computing & Data Sciences. A view of the center from the BU Bridge, July 8, 2022 (far right). Photos by Cydney Scott

And for more than a decade, Brown has been singularly determined that BU be at the forefront of data science, which has become so ingrained in society that “data scientist” is now one of the hottest jobs in the country. The opening of the dramatic new building on Comm Ave became a physical testament to Brown’s vision, but another important move was the appointment of Azer Bestavros, a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor and CAS computer science professor, as BU’s inaugural associate provost for computing and data sciences, tasked with building out the new Faculty of Computing & Data Sciences.

Building a world-class faculty using a unique, collaborative, cross-school structure, Brown says, is what will ultimately separate BU’s strategy from its peers. “We’ve got to focus, to pick our spots, and carefully put our resources on what’s most important.”

The challenges and humanity of leading

Someone who can closely relate to Brown’s decision to retire is his longtime friend and one-time colleague Larry Bacow, who announced earlier this year that he was stepping down as the 29th president of Harvard University. Bacow and Brown worked together at MIT in the 1970s and remained close through their parallel presidencies. As young men, they lived a block apart in Arlington when both were junior faculty members at MIT, and years later, their sons were fraternity brothers.

“I think he’s been a transformative president for BU,” Bacow, who spoke at Brown’s 2006 inauguration, says. “By virtually any metric, BU is a stronger place than it was when Bob arrived. It became a member of the AAU. And he played an important role locally among the community of Massachusetts college presidents. He put [in place] the protocols that guided many of us through the pandemic.”

Bacow lauds Brown’s straight talk for getting things done. “Bob is an engineer at heart. He’s incredibly straight with people. He doesn’t play games. He says what he thinks, but he’s also a good listener. He knows how to get things done and then delivers on his promises.”

The breadth of change occurring during Brown’s tenure reflects the vision he first outlined inside a packed Agganis Arena at his April 2006 inauguration, when he listed five themes that he vowed would define his presidency: learning, excellence, connectivity, engagement, inclusion. “I truly believe that universities are places where dreams come true,” he said that day, “where having an imagination is paramount and where hard work and intelligence are all that matter to excel in education and research.”

One unquestionable, and highly visible, shift at BU under Brown has been the hiring and promotion of women to many of the University’s most prominent and visible positions. In addition to bringing Morrison on board in 2011 as provost and chief academic officer, Brown named Gloria Waters, former dean of Sargent College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences, as vice president and associate provost for research, and more recently, Amanda Bailey as vice president of human resources, Judy Platt as chief health officer, Karen Engelbourg as senior vice president for development and alumni relations, Andrea Taylor (COM’68) as senior diversity officer, and Tracy Schroeder as vice president of information services. And it was under Morrison and Brown jointly that the leadership of BU’s schools and colleges took on a new look: today, 7 of the 17 are headed by women deans. The first sign of change came in 2007, when Virginia Sapiro was named the first woman dean of CAS. Other new appointments: first Maureen O’Rourke, then succeeding her, Angela Onwuachi-Willig, as dean of the School of Law, Susan Fournier, at the Questrom School of Business, Mariette DiChristina (COM’86) at the College of Communication, Natalie McKnight at the College of General Studies, Tanya Zlateva at Metropolitan College, and Sujin Pak at the School of Theology.

“I really believe that women, especially in science and engineering, but women overall in the academy, were an under-tapped resource,” Brown says of this shift. “It is clear there have been situations of bias against them, that they had to work harder and do better than men to be recognized in the academy. I think we’ve become known as a place where women leaders can come and succeed. This is wonderful recognition for the University.”

I think we’ve become known as a place where women leaders can come and succeed. This is wonderful recognition for the University.

(Brown’s passion for expanding the leadership opportunities for women started during his time at MIT. His role in the Emmy-nominated documentary film Picture a Scientist tells part of this story.)

Not every hire has been perfect, Brown acknowledges, and not every decision has gone as planned. But 17 years after he started, and with the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic behind the country, Brown says that upon reflection he doesn’t regret any decisions he made—he just wishes some of those decisions had been articulated more clearly to the BU community. “There were times we definitely could have communicated better,” he says. “But in terms of the decisions themselves, I don’t second-guess any of them.”

Like any college president, Brown has dealt with his share of community sadness. He ushered the University through two especially somber periods—the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, which killed a BU student, and the deadly and devastating COVID-19 pandemic.

Lu Lingzi (GRS’14), a graduate student in mathematics and statistics, was one of three people killed near the Marathon’s Boylston Street finish line in the deadly blasts. BU has endowed a memorial scholarship in Lingzi’s name. Brown compares the immediate aftermath of the Marathon tragedy, when the streets of Boston were shut down by police as they searched for the bombers, to the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when businesses were forced to shutter amid a rapidly spreading disease.

“Everybody went off and basically went underground,” he says. “The streets were deserted. We didn’t know anything, and everyone was just scared.”

Navigating through a pandemic

Like all current college presidents around the country, including nearly a dozen in Massachusetts who recently announced their own planned departures, Brown’s leadership tenure will be remembered in part for how he handled the coronavirus and dealt with the surging mental health crisis across college campuses. BU established its own on-campus clinical testing lab, at a cost of nearly $100 million, which enabled the University to regularly and rapidly test students, faculty, and staff for the coronavirus, so that in-person learning and residential life could be reestablished and maintained as safely as possible. (Brown was also asked by the state to help lead the overall school reopening efforts.)

“The interesting thing about the lab was that it became sort of the stake in the ground for us,” Brown says. “The lab was our way of saying, ‘We’re coming back, we’re not going to stay remote.’ It was a physical manifestation of coming back, and it took on an almost supernatural element in getting back.”

Brown, who is notorious among students for wheeling a briefcase behind him wherever he goes on campus (it puts less strain on his tired back, he says), has high praise for the student-driven masking and social-distancing campaign created during the early days of the pandemic: the award-winning ad campaign F*ck It Won’t Cut It.

“What that did, in the students’ own voice, was make the students partially responsible for the success of keeping the campus safe,” he says. “People understood that there’s a level of personal responsibility in not only your own health, but in the health of others.” He says it gave BU faculty and staff confidence that the students were going to take COVID seriously. “There were naysayers who said the students are just going to have one great big party, and everybody will get sick and the whole effort will collapse. And as you know, the students didn’t do that.”

There were naysayers [during the pandemic] who said the students are just going to have one great big party, and everybody will get sick and the whole effort will collapse. And as you know, the students didn’t do that.

His COVID-related decisions were challenged by some as putting revenue ahead of the health and safety of the BU community. But Brown was steadfast, insisting that BU is a residential campus and that long-term remote learning would cause more harm than good for students already struggling with issues of isolation, anxiety, and depression.

The mental health crisis on college campuses weighs on him, he says, because he knows how much students are struggling, especially during the pandemic. But he also credits the current generation of college students for being more willing than previous generations to talk and share openly what they are experiencing, and he says that’s a hopeful sign.

“Universities are doing their best to respond, with a combination of different support structures, some with professional mental health therapists and counselors, and by building support structures,” Brown says. “We’re still learning how to balance those approaches. COVID made this much more complicated. This is going to continue to be a major issue in society and on college campuses for years to come.”

While high-profile decisions and issues garnered the most attention, it was smaller, less visible moves under Brown, some driven by students, others by staff or faculty, that reflect his desire for a campus that encourages diversity, equity, and inclusion, as well as creative solutions to societal issues. Multiple surveys around DEI have taken the pulse of the BU community, with the intention of implementing changes around the hiring, promotion, and retention of employees.

A student-driven example came when students pushed, and won approval, for a vending machine stocked with Plan-B contraception at a time when abortion rights were on the verge of being struck down. That vending machine won national attention and other schools have since moved to install their own.

An example of inclusion from the early days of Brown’s presidency involves the rising number of Middle Eastern students at BU, many of them Muslim, and many who pass through the Center for English Language & Orientation Programs (CELOP). Because Muslims are required to perform ablution (the washing of hands, face, and feet before prayer), it was important for them to have footbaths, something that was not available at BU. So in 2011, the CELOP bathrooms were updated with footbaths so the students were no longer forced to wash in the sinks, a change that was not only a first for BU, but prompted other schools to follow suit.

Dropping the puck to open the 2005-2006 Terrier men’s ice hockey season October 15, 2005. Photo by Frank Curran

Dropping the puck to open the 2005-2006 Terrier men’s ice hockey season October 15, 2005. Photo by Frank Curran

Another cultural change that occurred under Brown involves athletics. Although BU has never been known as an athletic powerhouse, joining the Patriot League in 2012, a Division I conference with schools like Navy, Colgate, and Lehigh that place a high value on the academic performance of student-athletes, dramatically increased the profile of all athletics programs. The result has been consistently high numbers of Terrier student-athletes making the Patriot League honor roll, while also helping to lead teams to new success. In recent years, the women’s soccer team, the men’s and women’s basketball teams, the men’s lacrosse team, the softball team, and the women’s rowing team all won a championship or competed in a championship game.

As political tempers flared in the last decade, especially during the Trump administration, and the liberal-conservative divide grew more intense, Brown never wavered in his position that universities must not stand in the way of free speech.

“If I draw the line, if I say, I know where that line is, between what we shouldn’t listen to and what we should, we are on a very slippery slope that could be viewed as censorship,” he says. “Then people will believe that there is someone who’s going to monitor what they’re exposed to. And I just don’t think that’s the role of the university, or especially, the president.”

Finding financial stability

Brown brought stability to BU at a tumultuous moment in its long history. After the University initially hired Daniel S. Goldin as president in 2003, the trustees rescinded the offer, gave Goldin a severance package to walk away, and appointed Aram V. Chobanian (Hon.’06), dean of the BU School of Medicine and provost of the Medical Campus, as interim president. A new search began that ended with the unanimous decision to hire Brown, who at the time was across the Charles River as provost of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“I can’t think of a more accurate description of him than transformational,” says Robert Knox (CAS’74, Questrom’75, Hon.’17), a former BU Board of Trustees chairman. “He literally transformed BU. His accomplishments are too numerous to count.”

Knox recalls that before Brown accepted the presidency, he did a complete analysis of the University to have a grasp of what challenges he would face. “By the time he started, within just two or three months, he had a strategic plan ready to go,” he says. “He anticipates risks and threats probably better than any CEO I’ve worked with.”

Those skills paid off, Knox says, during two crises that bookended Brown’s tenure—the country’s 2007 to 2009 recession and the COVID-19 pandemic. And his management style and background also proved critical in the delicate process of getting the NEIDL approved.

“Getting the NEIDL through all the hoops, with the courts, the neighborhood, the government, was amazing and that will be a hugely prestigious part of the University for years to come,” Knox says. “BU is a complex organization, and he grasped how all the parts worked, how our debt worked, how our endowment could grow. It was incredible.”

Brown’s strategic plan for the University solidified a financial strategy for one of the largest employers in the state. His approach in the strategic plan was to create a “virtual cycle,” where more revenue was generated from University operations and from endowment income, and that growth was then reinvested into BU’s core programs to improve their quality and reputation. That, in turn, would generate increased giving by alumni and BU friends, and a larger pool of applicants to the University.

By many measures, Brown’s plan worked.

A few years later, BU’s first-ever capital campaign launched, and it was a roaring success. The initial goal of $1 billion was surpassed and increased to $1.5 billion, and by the time the campaign ended in 2019, the amount raised was $1.8 billion, which helped channel hundreds of millions of incremental dollars into teaching, research, and capital improvement projects. The overall endowment under Brown has more than quadrupled, to roughly $3 billion.

Still, there were challenges. In 2021, amidst the financial impact wreaked by the pandemic, Brown made the decision to lay off approximately 250 employees when faced with a nearly $100 million budget shortfall.

“His business model was based on generating revenue and reserves, which you reinvest in teaching and the research enterprise,” Gary Nicksa, BU senior vice president and chief financial officer, says. “And he wanted to increase the applicant pool and increase giving from alumni. Bob was extremely disciplined in executing his vision. As an engineer, he was the most data-informed executive I have ever worked with.”

And just as Brown started his presidency by creating BU’s first strategic plan, called Choosing to Be Great, he leaves the University positioned for the future with BU2030, a new vision for the future with five pillars: A Vibrant Academic Experience; Research That Matters; Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion; Community, Big Yet Small; and Global Engagement.

“I believe we are at an inflection point where the societal roles of universities are being redefined,” Brown wrote of that plan. “Developing our vision for the University in 2030 gives us the opportunity to lead in a rapidly changing environment.”

Relationship-building boosts BU

Many of the decisions and successes BU experienced under Brown, both internally and externally, have come as a result of the strategic plan he laid out in 2007, shortly after President George W. Bush appointed him to the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. In that 10-year vision, Brown put BU’s initial focus on strengthening programs that were already University core programs, while at the same time recruiting and expanding in areas he saw as opportunities for growth.

Brown says one of his most important acts came in his first month on the job, when he created a University Leadership Group, which includes leaders from across the University, on the administrative side and on the faculty side. Until that point, he says, BU faculty felt that decisions about the direction of the University were often made without their voice. “I put them in the room together,” Brown says. “I still remember that very first meeting, where people were literally introducing themselves for the first time.”

“What Bob did,” Morrison says, “was elevate the role and visibility of the faculty to where they should be—front and center, helping to provide intellectual and academic stewardship of the University.”

She says that Brown has also made it a point to bring BU’s average faculty salary in line with its peers. “We were in the lower quarter of our competitive set of institutions, and now we’re above the midpoint,” she says, adding that there was a particular disparity when it came to gender pay, and Brown was determined to wipe that out. “He really should get credit for that,” she says.

An important element of Brown’s strategic plan required strong relations with the city of Boston. During Brown’s tenure, he worked closely with four mayors. When Menino, then city mayor, signed off on the Charles River Campus Institutional Master Plan in 2013, it opened the door for a series of strategic changes on the Charles River Campus that ultimately helped boost BU’s prominence and allowed it to not only grow physically, but to gain stature in the community.

“I was blessed to start with Tom Menino,” Brown says. “He taught me a lot about how the city and University could work together.” And he came to realize something over time. “The University thrives as an urban campus when the city around us is thriving,” he says. “When the city of Boston is looked at as a good place to live, then we are looked at as a good place to go to school.”

October 28, 2010 groundbreaking for BU School of Medicine Student Residence on Albany Street: Ashraf Dahod (from left); Joe Fallon, Fallon Towle Associates; Sherry Leventhal, MED Advisory Board; Shamim Dahod (CGS’76, CAS’78, MED’87); President Robert A. Brown; Mayor Thomas Menino (Hon’01); MED Dean Karen Antman; and Catherine Spina (CAS’04, MED’05,’15). Photo by Vernon Doucette

October 28, 2010, groundbreaking for the BU School of Medicine Student Residence on Albany Street: Ashraf Dahod (from left); Joe Fallon, Fallon Towle Associates; Sherry Leventhal, MED Advisory Board; Shamim Dahod (CGS’76, CAS’78, MED’87); Brown; Boston Mayor Thomas Menino (Hon.’01); MED Dean Karen Antman; and Catherine Spina (CAS’04, MED’05,’15). Photo by Vernon Doucette

That strong relationship with the city plays out in various ways, big and small. When Menino wanted to raise additional revenue for city operations through increased payments-in-lieu-of-taxes (PILOTs) from its 48 largest private tax-exempt institutions, he named Brown the task force cochair. BU has also strengthened its ties to the Boston Public Schools (BPS) under Brown. The BU Menino Scholars Program offers full-tuition scholarships, based on strong academic achievement, to BPS high school graduates. And Brown created the Boston Service Scholars Program, where the University meets the full financial need without loans for BPS graduates. (In a typical year over 80 BPS graduates enter the University supported by one of these programs.)

On a smaller scale, BU has been there for the city when needed. When a high school in Charlestown had to move its 2022 graduation ceremony because of a nearby shooting and the city asked for help, the University immediately found a space for the ceremony.

BU’s stature under Brown has also increased with developments like EPIC, the Engineering Product Innovation Center. In addition to being funded by College of Engineering alums and the University, the center received a $19 million gift in 2013, allowing it to overhaul its curriculum so that all students, regardless of major, had access to developing new products and tapping their inner entrepreneur through software, 3-D printers, robotics, laser processing, and more.

After EPIC took off, it seemed to bring a tidal wave of change to BU, some of it academic, some of it cultural. Innovate@BU opened to support entrepreneurs across BU with support from the University and alumni. In 2014, a donation from Frederick S. Pardee (Questrom’54,’54, Hon.’06) gave birth to the Pardee School of Global Studies, with a mission of improving the human condition around the globe, and in 2015, the School of Management was renamed the Questrom School of Business in recognition of a gift from Allen Questrom (Questrom’64, Hon.’15), and his wife, Kelli Questrom (Hon.’15). The school has since had huge success with an online MBA program to complement its on-campus undergraduate degree and graduate programs.

A surprising gift of special importance to Brown came in 2019, when Newbury College, after more than half a century of educating and serving a large number of underrepresented students who were the first in their family to attend college, announced it was shuttering and donated $6 million to BU. The University used those funds to create the Newbury Center, which provides support to first-generation undergraduate, graduate, and professional students. Currently, 17 percent of undergraduates and 18 percent of the Class of 2026 are first-gen students.

Nicksa says that even though revenue to the University roughly doubled during Brown’s tenure, the amount of financial aid to students that BU disburses nearly quadrupled, to about $400 million. The result has been a transformational increase in the number of Pell Grant students and underrepresented minorities attending BU.

“That aid has come at the expense of other things, like some capital projects, we might have done,” Nicksa says. “But access to BU is absolutely something Brown has worked to achieve.”

And unquestionably, the admissions picture at BU is nothing like it was when Brown started. The number of students applying to BU has more than doubled under Brown, from more than 31,000 to more than 75,000, and at the same time, student selectivity became more competitive, as the acceptance rate dropped from 57 percent to 14 percent.

Touched by a parent’s story

Brown recalls one particular interaction he had with the parent of a first-generation BU student that reinforced to him the ways a University can change lives. He was attending an event at the Booth Theatre, and at the crowded reception a man approached to thank him for the financial aid package that allowed his daughter to attend BU.

“He said this is a beautiful place and that he had no idea we had our own theater,” Brown says. “I walked him back into the production area, and explained this is where sets are painted and put together.” The stunned father asked Brown if students did that work, or professionals. “I told him students do it all. We teach them how to do it. That’s part of the education, that they put up the productions and students come in to watch.”

Brown says that a light bulb seemed to go off in the father’s head. “His daughter had a father who really cared deeply about her, and he had no idea of what experiences she could have here because he had never experienced any of those things,” he says. “It showed me that there really is a benefit for all the mentoring and advising that we do of first-gen students, and all that we do to make their experiences better and more equal with everyone else.”

One highlight of Brown’s tenure came in 2018, when civil rights leader John Lewis (Hon.’18), the late Georgia congressman, addressed BU’s Commencement and issued a rousing call to action for graduates. “Be optimistic,” he urged them. “Don’t get lost in a sea of despair, but be bold, be courageous, and all will work out.”

President Brown, (right) and trustees Andrea Taylor (COM’68) and Kenneth Feld (Questrom’70) presenting an honorary degree to US Congressman John Lewis (D-Ga.) during the 2018 Boston University Commencement May 20, 2018. Photo by Michael D. Spencer

Brown (right) and BU trustees Andrea Taylor (COM’68) and Kenneth Feld (Questrom’70) presenting an honorary degree to US Congressman John Lewis (D-Ga.) during Boston University’s Commencement, May 20, 2018. Photo by Michael D. Spencer

Brown says he carries that same optimism about BU’s future.

“When I came here, I remember all the people telling me how horrible the campus was, and how could you have a campus with a streetcar that runs down the middle of it? They told me that it didn’t look like a campus. Well, we are never going to look like that. But we’re not apologetic about where we are. And if you look up and down Comm Ave today, with everything that’s happened, we look a lot better than we did.”

It didn’t happen overnight, he says. It required patience, and it required putting the right people in the right positions and giving them the resources to thrive, to learn, and to grow.

“I think we’re just a very different University today, not just for students, but for faculty and staff, too,” Brown says. “We’re much more mature. We’re much more confident. And most important, we’re much more competitive than we’ve ever been. I think the best is yet to come.”

President Brown addresses students, parents, and guests at the 2012 Matriculation, held at Agganis Arena on September 2. Photo by Cydney Scott

Brown addressing students, parents, and guests at the University’s 2012 Matriculation, held at Agganis Arena on September 2. Photo by Cydney Scott

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.